-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Grants

-

IDF surveys

-

Participating in clinical trials

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Clinician education

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Grants

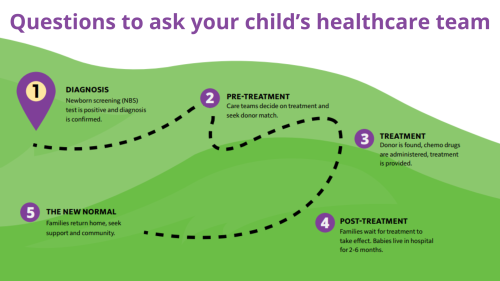

Newborn screening is a service provided by state public health laboratories that ensures all babies are screened for certain conditions that can cause serious health problems within 24-48 hours after birth. Many babies born with these conditions do not show any signs at birth and appear healthy. By screening all babies, this testing can change a baby’s life by helping health professionals make a diagnosis early and begin treatment before serious problems develop.

What PIs are currently part of newborn screening?

In 2010, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the addition of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) to the recommended uniform screening panel (RUSP). As of 2018, all 50 states in the U.S. screen babies for SCID. Because the blood test used to screen for SCID measures T cells, it also flags infants with related T cell deficiencies, including DiGeorge/22q11.2 deletion syndrome and ataxia-telangiectasia.

Screening tests for other types of PI are still in the research stage. Testing called Kappa rearrangement excision circles (KRECs) estimates the number of immature B cells, which are low in PIs like X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA). In the future, it may be possible to sequence a newborn’s entire genome and identify all or most types of PI. However, both technical and ethical challenges of this type of testing must be addressed first.

How are new conditions added to newborn screening?

New conditions are nominated by the public and reviewed by the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, which is run by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Accepted conditions must have:

- Serious health consequences if not detected early.

- At least one standard treatment that mitigates negative health outcomes.

- Evidence that early detection improves health outcomes for the condition.

- A validated clinical laboratory test that is feasible for public health laboratories to perform on a wide scale.

- A confirmatory diagnostic test that can be performed on positive samples.

- Evidence from a pilot study that screening newborns for the condition benefits public health.

Once a condition is added by the committee to the RUSP, states decide on when and how to implement screening for the condition. Ten states have passed RUSP alignment legislation requiring screening for new conditions added to the RUSP to be implemented by the state public health lab within a certain amount of time, typically two years. RUSP alignment legislation ensures that states don’t lag behind on screening for serious conditions and provides funding for the addition of new screening tests to a state’s current panel.

As technology emerges, there will be more newborn screening tests available for types of PI that are not detected with the SCID screening test. Building on previous success with SCID, IDF is prepared to advocate for another nationwide newborn screening campaign for additional PI conditions when such technology is feasible.

Sign up for Action Alerts

When we need policymakers to hear the PI community’s perspective, you will receive an Action Alert by email. Customize each alert with your information and hit send. It's that easy.

Sign up todayThe history of SCID newborn screening

Read about IDF's role in implementing newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) across the U.S.

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309