-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Respiratory viruses can cause serious illness

- For some respiratory illnesses, particularly COVID-19 and RSV, primary immunodeficiency (PI), also known as inborn errors of immunity (IEI), is a risk factor for severe infections.

- Get emergency medical attention right away if you have:

- Trouble breathing.

- Lasting pain or pressure in your chest.

- Severe sore throat with fever.

- New-onset confusion.

- Inability to wake up or stay awake.

- Pale, gray, or blue-colored skin, lips, or nail beds, depending on skin tone.

- Vomiting or diarrhea leading to dehydration.

- A fever over 103°F.

Respiratory viruses and PI

Several viruses that cause respiratory infections tend to spread and cause more illness from the late fall through early spring (about October through March) in the U.S. These viruses include COVID-19, influenza (flu), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and rhinovirus (which causes the common cold). Because people with primary immunodeficiencies (PIs), also called inborn errors of immunity (IEI), are more likely to get respiratory infections and may get seriously ill, it’s important to prepare for respiratory virus season.

COVID-19, sometimes known as COVID or coronavirus, is caused by a coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2. Symptoms vary from person to person, with some people experiencing no or mild symptoms, while others experience life-threatening disease. COVID-19 symptoms can include fever or chills, cough, fatigue, muscle or body aches, headache, new loss of taste or smell, sore throat, stuffy or runny nose, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, and shortness of breath.

People with COVID-19 are most contagious within the first five days of symptoms but can infect others up to 14 days or longer. Note that people who are immunocompromised, including those with PI, can have prolonged infections that last for a month or more. People who are infected with COVID-19 but have no symptoms are also contagious and can still spread it to others.

Risk factors

There is no good data on whether those with PI are more likely to get COVID-19 than others. Certain risk factors make people more likely to have severe COVID-19, but anyone can develop severe disease, even individuals who have had mild COVID-19 in the past. Importantly, older age is the single greatest risk factor for developing severe COVID-19. An analysis of adults hospitalized in 2020 found that those 65 and older were more than six times more likely to die from COVID-19 than adults 18-39 years old.

PIs that disrupt the type I interferon response like TLR7 deficiency or autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1 (APS-1, also known as autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy or APECED) place individuals at very high risk for developing severe COVID-19. The interferon response is critical for controlling the virus early on and, without it, the virus spreads rapidly in the body.

The data for most other types of PI are less certain. However, a large CDC study looking at healthcare records found that adults with PI and COVID-19 who went to the emergency room were hospitalized, were admitted to the ICU, were put on ventilators, and died at higher rates than those without PI. The increased risk ranged from 1.4 (ventilation or death) to 2.4 (hospitalization) times those without PI.

In addition to PI, certain medical conditions, including some that tend to co-occur with or result from PI (bolded below), make it more likely that someone will develop severe COVID-19.

- Asthma.

- Cerebrovascular disease (e.g., stroke, aneurysm).

- Chronic kidney disease.

- Chronic lung diseases:

- Bronchiectasis.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Interstitial lung disease.

- Pulmonary embolism.

- Pulmonary hypertension.

- Chronic liver diseases:

- Cirrhosis.

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

- Alcoholic liver disease.

- Autoimmune hepatitis.

- Cystic fibrosis.

- Dementia.

- Diabetes.

- Disabilities, including Down syndrome.

- Heart conditions:

- Heart failure.

- Coronary artery disease.

- Cardiomyopathies.

- HIV.

- Leukemia and lymphoma.

- Mental health conditions:

- Mood disorders, including depression.

- Schizophrenia.

- Obesity (BMI >30).

- Parkinson’s disease.

- Pregnancy and recent pregnancy.

- Tuberculosis.

Medical treatments and behaviors can also be risk factors for severe COVID-19, including:

- Being a current or former smoker.

- Being physically inactive.

- Being the recipient of hematopoeitic stem cell or solid organ transplant.

- Use of immunosuppressants like corticosteroids.

Risk factors are cumulative, which means that the risk of developing severe COVID-19 increases for every additional risk factor a person has. For example, a person who is 18 years old with an antibody deficiency (one risk factor) is less likely to become severely ill with COVID-19 than someone who is 65 years old with an antibody deficiency and bronchiectasis (three risk factors).

People who have had COVID-19 can also develop two very different complications after their initial infection—multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C (children)/MIS-A (adults)) or long COVID. Again, while there are factors that increase a person's risk, anyone, including children and those with mild COVID-19 symptoms, can develop these complications.

What is multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C/MIS-A)?

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) is a life-threatening condition that develops up to eight weeks after a COVID-19 infection. MIS-C affects about 1 in 10,000 children who have had COVID-19, but there are also reports of MIS in adults (MIS-A). Those with MIS-C/MIS-A have a fever above 100° F (38°C) for more than 24 hours with evidence of inflammation throughout their bodies, including:

- Stomach pain, diarrhea, or vomiting.

- Bloodshot eyes.

- Dizziness or lightheadedness.

- Confusion or seizures.

- Skin rash.

- Swelling of the hands, feet, lips, or tongue.

- Signs of shock.

Seek medical attention immediately if you have MIS-C/MIS-A symptoms.

Certain types of PI that include immune dysregulation are associated with developing MIS-C. Genetic studies of children with MIS-C have identified variants in the following PI-related genes:

- AP3B1: Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, type 2.

- C6, C9: Complement deficiency.

- CYBB: Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD).

- IFNAR1: IFNAR1 deficiency.

- LRBA: LBRA deficiency.

- LYST: Chédiak–Higashi syndrome.

- PRF1, STXBP2, UNC13D: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

- SOCS1: SOCS1 deficiency.

- TLR3: TLR3 deficiency.

- WAS: X-linked thrombocytopenia.

- XIAP: X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 2 (XLP-2).

There are no data on whether individuals with other types of PI, such as antibody deficiencies, are at increased risk for MIS-C/MIS-A.

What is long COVID?

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine defines long COVID as a chronic condition that lasts at least three months after the initial COVID-19 infection. Symptoms vary and can include shortness of breath, cough, persistent fatigue, fatigue after exercise or exertion, cognitive problems such as brain fog and memory changes, recurring headache, lightheadedness, rapid heartbeat, sleep problems, problems with taste or smell, bloating, constipation, and diarrhea.

Around 6% of adults and 1% of children develop long COVID according to estimates. There isn’t much research on long COVID and PI, but one study of healthcare claims within a nonprofit health system in New England found that those with PI were about three times more likely to have a long COVID diagnosis after infection compared to people without a PI diagnosis.

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu," is a respiratory disease that comes on suddenly. Symptoms that vary from person to person. These symptoms can include aching muscles, sore throat, a dry cough, a runny or stuffy nose, tiredness, headache, a burning sensation in the chest, eye pain, sensitivity to light, and fever and/or chills (note that people with primary immunodeficiency (PI) may not spike a fever).

Although many people think of the flu as harmless, from 2010-2024, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that between 6,300-52,000 people died of flu-related complications each year.

The flu is caused by influenza viruses. The two main types that infect people, influenza A and influenza B, are genetically different. Influenza A can cause moderate to severe illness in all age groups and infects many species, including pigs, birds, and horses. Influenza B usually causes milder disease and primarily affects children. Both influenza A and influenza B strains cause seasonal outbreaks, typically during the fall and winter months in the U.S. See recent flu activity in your state.

People with the flu are most contagious 1-2 days before symptoms appear and for 4-5 days after. It takes 1-4 days for symptoms to appear once you are infected. While most people recover in a few days, some experience severe illness.

Risk factors and complications

People with PI are equally at risk of contracting the flu as those without PI. Except for those with interferon pathway deficiencies like IRF7 deficiency, people with PI are not necessarily at higher risk of developing complications from the flu unless they meet other high-risk criteria:

- Are 5 years old or younger (especially younger than 2 years old).

- Are 65 years old or older.

- Have asthma, diabetes, or chronic lung, heart, kidney, liver, metabolic, neurologic, or blood conditions, including conditions that may be complications of PI.

- Have had a stroke.

- Have a secondary immunodeficiency caused by disease (e.g., HIV or blood cancer) or medication (e.g., immunosuppressive therapy).

- Are pregnant.

The flu's most common complication is bacterial lung infections (pneumonia). Other complications include viral pneumonia, myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), and worsening of chronic lung conditions. See a healthcare provider right away if you have:

- Difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, or rapid, shallow breathing.

- Blue-ish lips or nail beds.

- Chest pain or pressure.

- Seizures.

- Signs of dehydration (not passing urine).

- Dizziness, confusion, or other signs of altered mental state.

- Severe muscle pain, weakness, or unsteadiness.

Reye's syndrome is another flu complication often related to using aspirin for fever that primarily affects children and causes severe vomiting and confusion. To decrease the chance of developing Reye’s syndrome, infants, children, and teenagers under 19 years old should not be given aspirin for fever reduction or pain relief.

In the U.S., RSV season typically lasts from October through April, with a peak in December or January. Symptoms include runny nose, coughing, sneezing, fever, and difficulty breathing. RSV has two subtypes, A and B, that differ genetically, but there is no difference in disease severity between them.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that between 190,000-350,000 people were hospitalized with RSV in the 2024-2025 respiratory virus season, mainly for breathing difficulty and dehydration. While most people recover, 10,000-23,000 people ultimately die from the infection or its complications. Along with chronic heart and lung disease, being immunocompromised is a risk factor for developing severe RSV.

Research on RSV in those with primary immunodeficiency (PI) has primarily focused on infants and children. A 2012 paper found that children with PI are 3.8 times more likely to be hospitalized for an RSV infection than children without a chronic condition. Studies in Japan and Spain found that, in particular, children with PIs that affect T cells (for example, combined immunodeficiencies) are at the greatest risk of hospitalization for RSV.

Preparing for respiratory virus season with PI

People with PI should discuss plans with their healthcare provider about dealing with respiratory illnesses before the season begins, including:

How and where will you get tested for influenza, COVID-19, or other respiratory viruses?

- You may want to have unexpired rapid home tests for influenza and/or COVID-19 on hand.

- Testing for other respiratory illnesses, such as RSV or strep throat bacteria, will require a visit to your healthcare provider, urgent care, or a pharmacy.

What antiviral medication does your healthcare provider recommend and how will you get it?

What symptoms should you pay particular attention to and when should you seek emergency care?

How to avoid respiratory viruses

One of the most effective ways to avoid getting sick during respiratory virus season is to get vaccinated. However, you can’t get vaccinated against all respiratory viruses, so protecting yourself from exposure is also important.

Respiratory viruses mostly spread through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks, or exhales. Others then inhale or come in contact with tiny droplets that have viral particles. The viral particles enter the body through mucous membranes in the nose, mouth, and eyes. Strategies like boosting airflow and avoiding sick people help protect you against transmission through the air.

Respiratory viruses can also be spread by touching a surface contaminated with the virus and then touching your face. Washing your hands and limiting how much you touch your face protect you against transmission through surfaces.

Stay up to date with your shots

Unfortunately, you can’t get vaccinated against all respiratory viruses. However, there are vaccines against COVID-19, influenza, and RSV that provide good protection against the big three that cause the most serious infections.

For influenza and COVID-19, the World Health Organization (WHO) updates its recommendations for which strains vaccines should target every year, since these viruses change quickly. Because these vaccines change every year to match circulating virus strains, everyone 6 months of age or older needs flu and COVID-19 vaccines every year.

Why should everyone be immunized? First, many people with PI develop at least some antibodies or a T cell response (which is important for controlling viral infections) to the vaccines.

Second, although immunoglobulin (Ig) replacement therapy products (IVIG or SCIG) contain antibodies to flu and COVID, they typically do not have protective levels of antibodies against current virus strains because manufacturing takes 9-12 months after the initial plasma donation. For people on Ig, flu and COVID-19 vaccines can provide an extra layer of protection. Also, people on Ig replacement therapy do not need to coordinate vaccine timing with their treatment for these seasonal vaccines.

Finally, household members of people with PI should get vaccinated to create a "protective cocoon" around the person with PI. This strategy decreased the chances the person with PI will come in contact with the viruses.

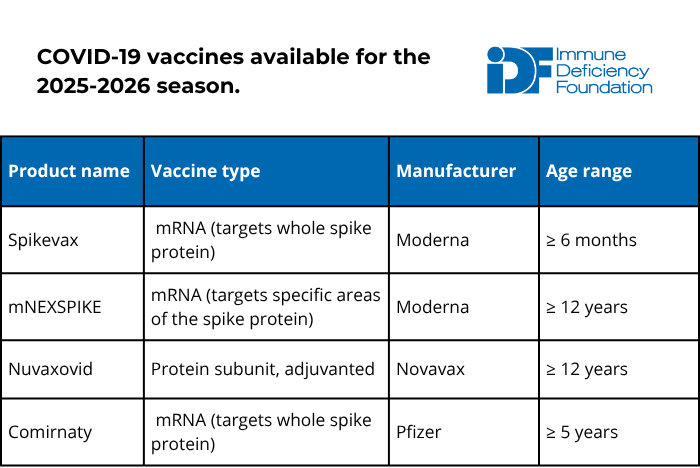

The current 2025-2026 COVID-19 vaccines target the LP.8.1 strain and became available in September 2025. Because of their limited FDA approval and a recommendation for shared decision-making by the CDC, accessing the 2025-2026 COVID-19 vaccine differs by state. Talk to your healthcare provider and/or pharmacy to find out where you can get the shot.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend that the following groups receive at least one dose of the most current COVID-19 vaccine:

- Everyone aged 6-23 months old.

- People aged 2-18 years old who:

- Are at high risk of severe COVID-19, including those with PI.

- Reside in long-term care facilities or other group settings.

- Have never been vaccinated against COVID-19.

- Live with individuals that are at high risk of severe COVID-19, including those with PI.

- Everyone aged 19 years old or older.

- AAFP recommends that people 65+ years old get two doses at least two months apart.

Discuss AAFP’s recommendations for those who are moderately to severely immunocompromised with your immunologist to determine whether you should receive more than one dose. In general, booster doses should be spaced out by at least two months.

The COVID-19 vaccine is safe and cannot cause COVID-19 in anyone, no matter how weak their immune system, because it does not contain live virus. Although there is no data in patients with PI, receiving the most recent COVID vaccine booster may prevent or reduce long COVID complications.

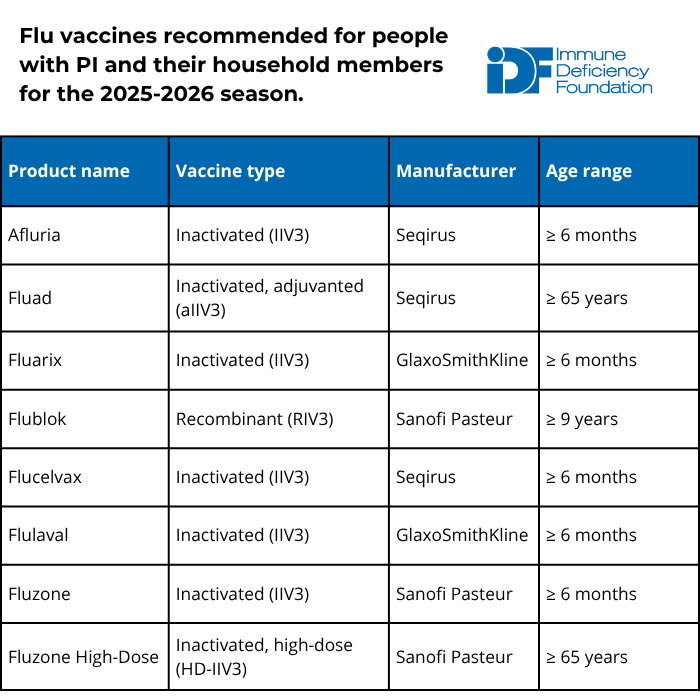

For the 2025-2026 season, all flu vaccines are trivalent, which means they protect against three different influenza virus strains: two influenza A strains and one influenza B strain.

There are multiple types of flu vaccines available and selecting the right type is important. The inactivated or recombinant flu vaccine types are best for people with PI and their household members. People with PI and their household members should not receive the live attenuated flu vaccine (trade name Flu Mist).

Additional recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) include:

- People aged 65+ should receive the high-dose inactivated, adjuvanted inactivated, or recombinant vaccine because these formulations provide greater protection in older individuals.

- Solid organ transplant recipients aged 18-64 who are on immunosuppressants can also receive either high-dose inactivated or adjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccines.

- Children 8 years old or younger who have not received at least two flu vaccine doses previously should receive two doses of flu vaccine spaced four weeks apart.

- People with egg allergy may receive any vaccine (egg-based or non-egg-based) that is appropriate for their age and health status.

The flu vaccine is safe, and the inactivated and recombinant versions cannot cause the flu in anyone, no matter how weak their immune system. The vaccine is available from late summer, and AAP and AAFP recommend getting vaccinated by mid-October for the best protection through flu season.

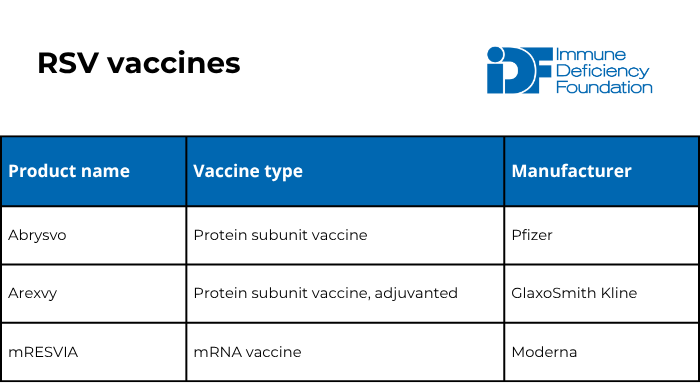

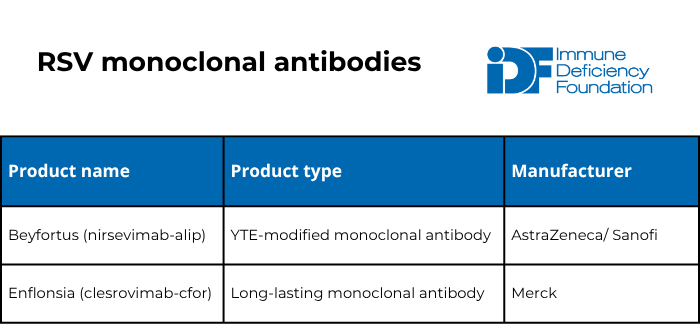

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved five preventative products for RSV within the last couple of years: three vaccines and two long-lasting monoclonal antibodies. Unlike vaccines, monoclonal antibodies are a type of passive immunization that provide protection regardless of how well a person’s immune system works. Monoclonal antibodies work like immunoglobulin replacement therapy but only protect against one specific germ.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommends that the following people get an RSV vaccine:

- Pregnant individuals who have not received an RSV vaccine previously. These individuals should get one dose of the Abrysvo vaccine when they are 32-36 weeks pregnant from September through January.

- People aged 50-74 who are at high risk of severe RSV infection (including those who are moderately or severely immunocompromised).

- People age 75+.

Unlike the flu and COVID-19, experts consider RSV vaccination protective for a long period of time. There are currently no recommendations for any group to receive more than one dose in their lifetime.

The RSV vaccine is safe and cannot cause RSV in anyone, no matter how weak their immune system, because it does not contain live virus.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends one dose of either of the two long-lasting monoclonal antibodies for:

- Babies 7 months old or younger born to individuals who have never been vaccinated for RSV or were vaccinated for RSV during a previous pregnancy.

- Babies 8-19 months old who are at high risk of severe RSV infection either because of a medical condition (including severe immunocompromise) or because of American Indian/Native Alaskan heritage.

Consider getting the anti-COVID-19 monoclonal antibody

The FDA approved pemivibart, made by Invivyd (trade name Pemgarda), in March 2024. Pemgarda is a monoclonal antibody, which means that unlike vaccines, it provides protection regardless of how well a person’s immune system works. It is meant to be used before exposure to prevent COVID-19 infections in those who are at least 12 years of age, weigh at least 88 pounds, and are moderately to severely immunocompromised. It is not approved for use after exposure or during infection.

Pemgarda is an intravenous infusion given every three months and must be prescribed by a healthcare provider. Infectious Disease Society of America’s clinical guidelines for Pemgarda can help healthcare providers determine if their patients should receive it. It is typically given at an infusion center or other healthcare facility and any facility can order it through their distributor; see Invivyd’s facility locator for help finding a location.

Stop the spread

While vaccines are a crucial tool during respiratory virus season, you should take advantage of other tools, too:

- Regularly wash your hands with soap and water for 20 seconds, especially after coughing or sneezing. If soap and water aren’t available, use hand sanitizer with at least 60% isopropanol or 70% ethanol. Note that hand sanitizer may not be as effective in killing germs as handwashing.

- Keep away from individuals who are sick.

- Disinfect high-touch surfaces in your home, like door handles and light switches.

- Try not to touch your nose, mouth, or eyes.

- In crowded indoor areas, use a well-fitted N-95 or KN-95 mask covering your nose and mouth to avoid inhaling droplets that can spread respiratory viruses.

- During respiratory virus season, those with PI should consider avoiding crowded indoor areas such as shopping malls.

- When coughing or sneezing, cover your nose and mouth with a sleeve, elbow, or tissue. Dispose of the tissue after use.

- Stay home from work or school while sick and consider masking around others for up to five days after feeling better.

Boost indoor airflow

Respiratory viruses spread through the air, so crowded, indoor spaces with poor airflow increase the possibility of a sick person infecting others. Simple actions you can take include:

- Opening windows and doors.

- Setting HVAC system fans to run continuously.

- Using high-filtration HVAC filters and replacing them often.

- Using air purifiers/cleaners that meet certain criteria.

What to do if you get sick

COVID-19, colds, RSV, and the flu have overlapping symptoms but are different respiratory illnesses with different treatments. Because symptoms alone can’t determine which illness someone has, it’s important to get tested if you feel sick. Note that it is also possible to get multiple respiratory illnesses at the same time.

If you feel sick, immediately test with an unexpired, rapid antigen test at home. In addition to many rapid antigen tests available for COVID-19, there are now a number of rapid antigen influenza A and B tests, as well as “multiplex” rapid antigen tests that test for COVID-19, influenza A, and influenza B all at the same time.

If the rapid test is negative, consider getting a more sensitive PCR/nucleic acid test for COVID-19 and/or influenza and testing for other respiratory germs, such as RSV or strep throat. Tests for these germs are typically available at pharmacies, urgent care centers, and healthcare provider offices.

If you test positive for COVID-19 or influenza A or B by either a rapid antigen test or a PCR/nucleic acid test, contact your healthcare provider to get and start antiviral treatment as soon as possible. Influenza antivirals are most effective within 48 hours of symptoms. COVID-19 antivirals are most effective within 5-7 days of symptoms appearing.

Note that many people delay antiviral treatment because they don’t feel ‘that bad’ initially, but mild symptoms can rapidly become serious. Don’t wait!

If you have a different respiratory illness, talk to your healthcare provider. There are no antiviral treatments for other respiratory viruses but if you have a bacterial illness like strep throat, you may need antibiotics.

There are several antivirals available to treat COVID-19, as well as convalescent plasma:

- Nirmatrelvir with ritonavir (trade name Paxlovid®).

- A pill that is taken twice daily for five days and must be started within five days of symptoms.

- Paxlovid is FDA-authorized for those 12-17 years of age and FDA-approved for those 18 years old and older. Use the FDA’s checklist with your healthcare provider to determine if you can safely take Paxlovid.

- Molnupiravir (trade name Lagevrio®).

- A pill that is taken twice daily for five days and must be started within five days of symptoms.

- Lagevrio is FDA-authorized for those 18 years old and older who cannot safely take Paxlovid.

- Remdesivir (trade name Veklury®).

- Remdesivir is given intravenously over three days and must be started within seven days of symptoms.

- It is FDA-approved for those 28 days old or older who weigh at least 3 kg.

- Convalescent plasma.

- Given intravenously in either an inpatient or outpatient setting as early as possible after infection.

- FDA- approved for patients who are immunocompromised.

There are four antiviral drugs approved by the FDA and recommended by the CDC to treat the flu. All four work on both influenza A and influenza B viruses. Three of the antivirals are also recommended for the prevention of influenza (i.e., prophylactic use).

- Oseltamivir phosphate (available as a generic or under the trade name Tamiflu).

- Available as a pill or liquid suspension and is FDA-approved for the treatment of flu within 48 hours of symptoms in people 14 days and older.

- The CDC also recommends prophylactic use in those ages 3 months and older.

- Zanamivir (trade name Relenza®).

- A powder that is administered using an inhaler device and is approved for early treatment of flu in people 7 years and older.

- It is also approved for prophylactic use in people 5 years and older.

- Note that it is not recommended for people with breathing problems like asthma or COPD or those with milk protein or lactose allergies.

- Baloxavir marboxil (trade name Xofluza®).

- A single-dose pill approved for the treatment of flu within 48 hours of symptoms and as post-exposure prophylaxis (i.e., after known exposure to the flu, but before symptoms begin) in people 5 years and older.

- Peramivir (trade name Rapivab®).

- Given intravenously by a healthcare provider and is approved for early treatment of flu in people 2 years and older.

Healthcare providers should start individuals with flu symptoms who test negative for COVID-19 on antiviral treatment as soon as possible when there is known influenza activity in the community, even before they get tested for flu, especially for people at high risk of developing complications. For those with PI, antiviral medication can also be given preventatively if a household member or other close contact becomes ill with the flu.

Keeping safe from COVID-19 at in-person events

The health and safety of all participants is of paramount importance to the Immune Deficiency Foundation as we return to in-person events.

- Overall, the foundation's guidelines prioritize the health and safety of all attendees and comply with the CDC's recommendations to ensure the success of in-person events. IDF event guidelines follow minimum federal requirements and consider more stringent state and local guidelines and those of the venue to ensure the safety of all attendees.

- While masks are not required, they are encouraged in spaces where social distancing is not possible. If you decide to wear a mask, please choose N95 or KN95 and change as often as needed. Masks will be available for attendees at no cost.

- Stay home when appropriate: If you have tested positive for COVID-19 (or flu or RSV), are waiting for test results, have symptoms, feel sick or unwell, or have had close contact with a person who has tested positive, please do not attend the event.

- Depending on the size of the event, attendees may be provided with a choice of lanyard noting their level of social distancing comfort.

- Depending on the size of the event, the foundation will note the air carbon dioxide levels of meeting rooms and notify attendees if levels exceed recommended readings.

- The foundation reserves the right to implement additional requirements in the event of a substantial increase in COVID-19 transmission rates in the county or surrounding counties.

Latest infectious disease resources

Foundation provides guidance amid changing vaccine recommendations

Foundation to follow medical societies' vaccine schedules in light of ACIP hepatitis B decision

Preparedness key when visiting emergency department with PI

This page contains general medical and/or legal information that cannot be applied safely to any individual case. Medical and/or legal knowledge and practice can change rapidly. Therefore, this page should not be used as a substitute for professional medical and/or legal advice. Additionally, links to other resources and websites are shared for informational purposes only and should not be considered an endorsement by the Immune Deficiency Foundation.

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309