-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

In the 1970s and early 1980s, many around the world learned about severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) for the first time when a Texas boy, David Vetter, was born with the disorder. SCID is a primary immunodeficiency where affected infants lack white blood cells called T cells that help fight infections caused by a wide array of germs. Affectionately known as ‘the boy in the bubble,’ Vetter lived in protected, relatively germ-free environments for years because the only treatment option at the time was a bone marrow transplant from a full-match donor. However, medical knowledge has progressed significantly since then and there are now treatments, including partial match bone marrow transplantation and gene therapy, that allow persons born with SCID to thrive.

The case for SCID newborn screening

In the medical community, SCID is considered a pediatric emergency. Babies with SCID appear healthy at birth, but without early treatment, these infants do not survive. In a 2007 paper, 94% of babies with SCID that received bone marrow transplants in the first 3.5 months of life survived. However, the survival rate dropped to less than 70% for infants who are transplanted after that age because any infections that develop prior to transplantation can cause permanent organ damage.

By screening all babies for SCID, health professionals can make a diagnosis early and begin treatment before serious problems develop.

Adding SCID to newborn screening recommendations

Prior to 2003, newborn screening was a state-level public health service with no federal coordination. Because of variability in the conditions each state included in their screening, the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) at the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) was established to perform evidence-based reviews and recommend a standard set of conditions to be included in all state newborn screening programs.

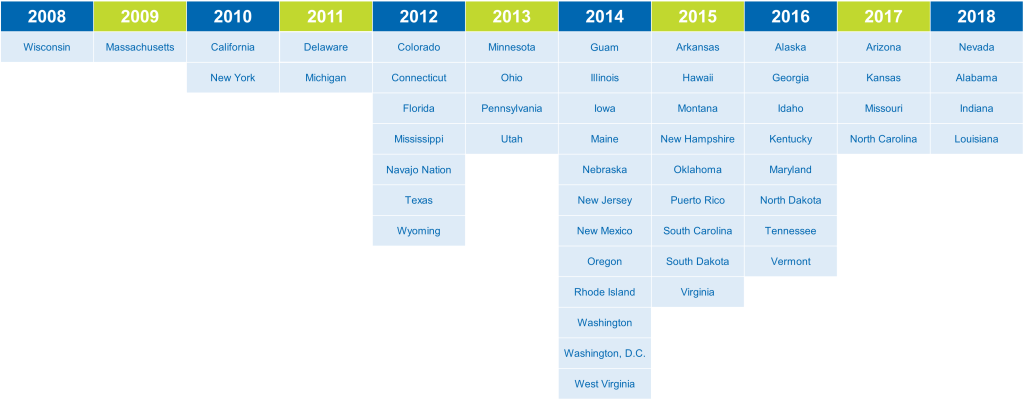

Two states, Wisconsin and Massachusetts, and specific hospitals within the Navajo Nation or associated with the Primary Immune Deficiency Treatment Consortium (PIDTC) began screening newborns for SCID in the late 2000s. Their pilot results provided necessary evidence to ACHDNC and helped justify the addition of SCID to the panel.

On May 21, 2010, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the addition of SCID to the core conditions of the recommended uniform screening panel (RUSP). SCID was the first new condition to be added to the RUSP via the evidence-based committee review process.

Implementing SCID newborn screening

However, ACHDNC’s recommendations are not binding. There is no set timeline or dedicated funding for states to implement screening for new conditions. Over eight years, IDF tackled the implementation of SCID screening by advocating on a state-by-state basis. As of December 10, 2018, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, the Navajo Nation, Puerto Rico screen all newborns for SCID.

The addition of SCID to newborn screening has revealed that it is more common than originally thought: current prevalence estimates put it at 1 in 58,000 births.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.