-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

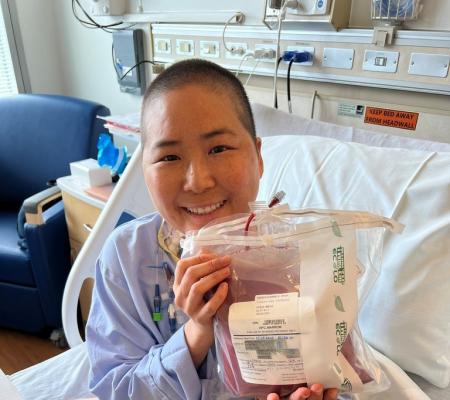

While treatment for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) can restore a person's immune system, the procedure doesn’t signal an end to coping with this life-threatening PI. A reconstituted immune system may fail, and side effects from the treatment may present lifelong challenges. Those with SCID must monitor their immune system and general health throughout their lives.

To address this topic, IDF interviewed SCID expert Dr. Jolan Walter, Division Chief of the University of South Florida and Johns Hopkins All Children's Pediatric Allergy & Immunology Program, during a SCID Compass podcast entitled, "Importance of Long-term Follow-up After Treatment." In the podcast, Dr. Walter discussed:

- details affecting the success of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), the most common type of treatment for SCID, and gene therapy, a treatment for SCID that is still in clinical trials

- risks associated with treatments including graft versus host disease, loss of the graft, malignancy, and dependence on immunoglobulin

- complications connected with conditioning/chemotherapy

- timetable for immune reconstitution

One of the more critical aspects of both short-term and long-term follow-up is chimerism. If a person receives an HSCT, which provides the child with donor cells to build an immune system, the level of chimerism in that person is tracked closely by doctors. Chimerism measures the ratio of T cells and B cells and what fraction of those belong to the baby, and how many are from the donor.

"It gives us upfront information about how the immune system is holding up," said Dr. Walter.

If there is low B cell chimerism, providers must check the B cell immunoglobulin levels, and the baby may need Ig therapy, said Dr. Walter.

If there is worsening T cell chimerism, this is of great concern because it points to a failing graft, meaning donor cells are no longer successful in building a full immune system for the child. Doctors must monitor the new T cells coming from the thymus in an assay from the child's blood and see how they multiply in a T and B cell proliferation study.

"These are terms you'll want to know and track with your doctor," said Dr. Walter.

In contrast, if a child undergoes gene therapy for SCID, doctors cannot do an assay because they are receiving their own corrected cells to build an immune system. Instead, doctors look to a copy number variation. If the number is high enough, then there is a useful function of the immune system.

Dr. Walter said a child treated for SCID should be monitored every three to six months for the first few years of their life. After about age 4, the child can be seen annually, although Dr. Walter prefers a visit every six months for her patients.

Transition from pediatric care to adult care can be challenging for patient and doctor, said Dr. Walter. "We have a hard time letting go. We have to educate our peers, but patients have to be ready to own their condition and have a high level of vigilance," said Dr. Walter.

Adults with SCID could encounter complications, including:

- Immune function decline

- Infection

- Autoimmunity

- Malignancy

Annual screenings are essential to making sure that a person with SCID remains as healthy as possible. To watch the podcast, click here. To read more about long-term follow-up for SCID, click here.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309