-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Alysia Padillo-Vaccaro learned her newborn daughter Evangelina Vaccaro had severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) just six weeks after Evangelina’s birth, and like most parents of children with SCID, Alysia and her husband Christian felt devastated by the diagnosis. But Evangelina had a twin – Annabella – and the couple was determined to mark the early days of the sisters’ bond no matter what the future held.

So, after they heard from the doctors, they called their photographer and told her to keep the appointment – with a few adjustments.

“We were scheduled for newborn photos on a Monday, and we got the news (of the diagnosis) on a Saturday, and, at first, I fell apart, and then I realized that I’m not leaving without taking photos of both of my twins because this could be the last time they are together,” said Vaccaro. “So, the photographer put on a gown and mask and took the photos – and then we went to the hospital.”

Today, Evangelina, who received gene therapy to treat her adenosine deaminase (ADA) SCID, is a healthy 10-year-old who likes tennis, horseback riding, swimming, surfing, and riding her skateboard. She’s had all her vaccinations, even the live ones, and received her COVID-19 vaccine and booster.

“She’s just the easiest-going, most caring kid you’ll ever meet,” said her mom. “And she can go into any situation and handle it.”

Perhaps Evangelina’s challenging start molded her into such a resilient child. Born on August 28, 2012, Evangelina and Annabella arrived five weeks early and stayed in the neonatal intensive care unit for 10 days.

Evangelina’s health began to decline when she arrived home. She vomited every time she ate, seemed sleepy all the time, and her skin had an unusual reddish tone. The pediatrician ran bloodwork and found low white blood cell counts (which she also exhibited at birth), but he told her parents not to worry – that it was normal.

“But I said, ‘No, something is wrong,’” said Vaccaro.

A third test showed low white blood counts again, and inconclusive results from newborn screening for SCID a second time. Doctors admitted Evangelina to the hospital. Further testing revealed that she did not have cancer and might have SCID.

“My heart sank,” said Vaccaro.

Doctors sent the family home and confirmed the diagnosis by phone about a week later. Evangelina entered the hospital again for about two weeks while doctors determined the type of SCID she had. They also tested her sister and parents to find out if they could be donors for a bone marrow transplant, the accepted treatment for SCID. None of them was a close enough tissue match.

As the Vaccaros considered using stem cells from an unrelated, partially matched donor for the bone marrow transplant, they learned of gene therapy trials for SCID at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA).

After conversations with UCLA stem cell researcher and head of gene therapy trials Dr. Donald Kohn, the couple decided to choose gene therapy for Evangelina’s treatment. Kohn explained the procedure thoroughly, discussed trial results, and answered their questions, said Vaccaro. He also connected them to the parents of other children in the trial.

“The main reason we chose gene therapy was because we knew that if it didn’t work, we could do bone marrow transplant. It just made better odds for Evangelina,” said Vaccaro. “You love your children, but you have to play the numbers game with your children and it’s scary and it’s heartbreaking.”

The family waited in isolation at home until December 2012 when Evangelina was old enough to undergo the procedure. The day after admission to the hospital, doctors collected her stem cells and took them to the lab so that they could be corrected by adding the functioning gene she lacked. A few days after, doctors administered chemotherapy and waited until Evangelina’s white blood cell count dropped low, to make room for the gene-corrected cells. Within about a week after being in the hospital, Evangelina underwent the transplant, receiving the gene-corrected cells through an infusion, which took only a few minutes.

While the gene therapy preparation and treatment took place over a few days, immune reconstitution began to take place in a month. Every other day for four weeks, doctors performed lab work on Evangelina to monitor the progress of her immune system.

“I was a lucky mom,” said Vaccaro. “Evangelina was calm. She made it look easy and she had an amazing disposition.”

Christmas time brought good news. Evangelina’s healthy cells were multiplying, and by January 2013 doctors released her from the hospital to isolation at home.

“Nothing will ever top that. It’s a gift from God. To know that science was able to give my daughter her life, to this day I stare at her and I’m in awe,” said Vaccaro.

Vaccaro recalls how joyous it was for her and her husband to remove their masks around their children in July finally.

“It was time for mommy and daddy to kiss and love on their babies,” said Vaccaro.

Evangelina and Annabella spent all their time together in isolation during Evangelina’s recovery at home, and their parents watched as their daughters met developmental milestones on time.

“When you think about it, I think God placed me with twins. For one, He blessed me after my losses, and two, when you have one healthy child and one sick child, you strive to keep the sick child healthy and you don’t give up and you can’t give up because the other child is depending on you,” said Vaccaro. “It grounds you.”

At the twins’ second birthday party, the couple invited friends and relatives - who didn’t wear masks or take any special precautions for germs. While it was wonderful to watch their family meet the girls, it was also nerve-racking, said Vaccaro.

“Christian and I were dying. Talk about taking the band-aid off,” she said.

Inspired by her daughter’s diagnosis, treatment, and recovery journey, Vaccaro served on the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) Patient Advisory Panel and as a patient advocate for the Americans for Cures, a California stem cell research advocacy organization. She provided input and guidance for the CIRM ADA-SCID gene therapy clinical trials and moved to a panel for Orchard Therapeutics when the pharmaceutical company took over the trials.

A few years later, she and other parents expressed their disappointment that Orchard lacked urgency in further developing the gene therapy treatment and urged CIRM to step in and transfer the trials back to UCLA, which occurred in May 2021.

“My fear is, not just with this trial but with all of them, we are setting an example with this therapy and this company for what others potentially may be like,” said Vaccaro. “To them, it’s not a big deal, but to me, it’s a huge deal.”

Vaccaro continues to work closely with the trial through her role as a patient advocate with Americans for Cures.

“I’m on calls with Dr. Kohn and his team every Friday. It’s amazing how much stuff they have to get together and have ready for the FDA. They are working tirelessly to get this done and it’s hard to be frustrated when I can see it’s not stagnant - they are working so dang hard and you can’t get mad at that because that’s the process you have to go through to get these therapies,” said Vaccaro.

Vaccaro said it’s difficult emotionally to know that while her daughter benefitted from gene therapy clinical trials, others with ADA-SCID must now wait.

“Here I am coming home to this beautiful healthy girl and the other parents don’t have that, so that is the frustrating part. I put myself in their shoes, other mothers who have been waiting for three or four years. It’s hard to comprehend what these families go through,” said Vaccaro.

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

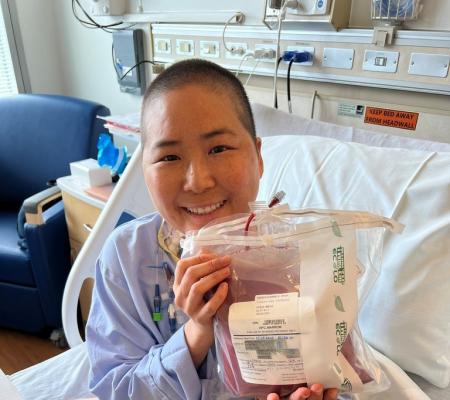

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.