-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Though the impact of primary immunodeficiency (PI) on the Coleman family grows with each passing year, parents Anna and Miles Coleman remain steadfast in their efforts to seek diagnoses and treatment for their children.

The Colemans have two children with common variable immune deficiency (CVID), 10-year-old son Asher, diagnosed six years ago, and son Knox, 5, who received his diagnosis just last year—the same year that their mom learned she has specific antibody deficiency (SAD). While immunoglobulin levels look normal in their other two children, son Aiden, 8, and daughter Addy, 3, the couple is having them tested for SAD, especially because Addy develops frequent infections.

“I would say this year has been particularly hard because my health issues have waxed and waned my entire life, but then you start to see it in your kids, and you don't want them to suffer. Part of this life is suffering, but you want to take the suffering for them,” said their mom.

The family’s journey with PI started when Asher, at age 2, developed a severe case of hand, foot, and mouth disease that progressed to impetigo, a skin infection. Frequent upper respiratory infections followed. Doctors prescribed antibiotics and told the Colemans that Asher would grow out of it.

“He was sickly often and you could tell his body was tired. It was hard for him to get up in the morning. He would complain that his body would ache,” said his mom.

Thinking Asher had allergies, the Colemans took him to a pediatric allergist/immunologist. The clinician suspected something different—an immune deficiency—and testing showed Asher, then 4, had CVID. He experienced breakthrough infections on prophylactic antibiotics and switched to subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) replacement therapy and, eventually, to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy.

As he experienced infections as a toddler, Asher regressed developmentally. His speech failed to progress, and he grew distant. His mother, a teacher for 14 years with a master’s degree in special education, suspected autism and testing confirmed her observations.

As the Colemans cared for Asher and his younger brother Aiden, Anna gave birth to Knox. Knox had a severe eye infection at two months old that required hospitalization.

“My motherly instinct told me maybe this is going to be something but let's just wait. Let's not do all of this testing on him yet,” said Coleman.

Knox had subsequent upper respiratory infections that required ear tubes and removal of his adenoids and tonsils. Last year, his health worsened with pneumonia and strep throat.

“At that point, we took him to the immunologist that Asher went to. I wanted his immune system tested. I felt like he had something going on because it was very reminiscent of Asher’s experiences,” said Coleman. “The doctor diagnosed him with CVID and started him off with large doses of plasma right off the bat.”

Anna Coleman’s own journey with chronic illness lasted decades. As a child, she had frequent ear infections and doctors hospitalized her for pneumonia. Being homeschooled improved her health, but in college sinus infections and bronchitis returned. Gastrointestinal issues caused Coleman to lose 20 pounds.

“They didn’t know why. They didn’t do any significant testing. They just said here’s some medicine. Try to gain 10 pounds. That should help,” said Coleman.

Pregnancy caused more infections and fatigue. Doctors attributed her poor health to pregnancies and breastfeeding.

“When I had my fourth child, I was so physically tired at times I couldn’t get out of bed, which is not like me,” said Coleman. “I was desperate. I was so mentally and physically drained that I was getting to the point where I couldn’t function to take care of my kids.”

Coleman visited her children’s clinical immunologist at Duke University Health System last year and asked for immune testing. At 39, she finally learned that SAD was the root cause of her sickness. Treatment with SCIG drastically altered her life.

“I told my husband by the time I got to my fourth infusion, ‘If this is what a normal person feels like, I’ve been missing out.’ I felt my brain fog starting to go and my energy levels coming back,” said Coleman. “I felt like I was getting my life back. I could finally function and take care of my kids again.”

Ig replacement therapy not only improved the PI symptoms in herself and her children, said Coleman, but also improved an autoimmune neurological condition that both Asher and Knox developed called pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS)/pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), or PANS/PANDAS.

PANS/PANDAS results in brain inflammation caused by an infection, PANS/PANDAS and presents as sudden and dramatic changes in personality, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, tics, and a decline in cognitive abilities. Over time, an increased dose of Ig began to significantly alleviate the symptoms, said Coleman, though Asher still lives with autism.

“Asher’s doing so much better now. There’s a noticeable difference. It’s pretty phenomenal. It’s just amazing to me. Knox is also doing great,” said Coleman.

“I guess what I’ve learned is how beneficial plasma has been, especially for Asher, not just in his physical health, but his neurological health. He is able to cope. His tics diminished, and a lot of the OCD went away.”

Asher, a fifth grader, attended school in person until this past school year when Coleman decided to homeschool. In solidarity, Aiden, a third grader, requested homeschooling too.

“Aiden has been the most amazing part of this whole experience. If you want to know how to treat someone with special needs, watch their siblings. Sometimes their siblings are their biggest advocates,” said Coleman.

Navigating the education system is a challenge, said Coleman. She tries to teach others about PI but not everyone is willing to listen, understand, and accept.

“I’ve learned not to take it personally because a lot of times—and I am guilty of this—we cannot fully understand something until we’ve experienced it.

“My children come first and my primary responsibility as their mom is to stand up for their needs. I think over the years, that’s caused some hurt feelings, but I think now knowing they have a PI and they’re on plasma, there are some answers to why they are sick all the time and that helps some,” said Coleman.

“You have to learn what’s best for your family and sometimes that’s an isolated, hard, and difficult road to travel. There are periods as a parent when you go through stages of grief for your kids. You just have to take it one day at a time.”

Coleman said parents of children with PI should remember to take care of themselves too and find support in communities, such as a faith-based organization or a network like IDF.

“Don’t be afraid to ask for help, even if you feel like people don’t understand what you are going through. Don’t try to be a hero and do everything yourself. We are human, and we can only handle so much,” she said.

Read other newsletter articles

The IDF ADVOCATE is the national newsletter of the Immune Deficiency Foundation, published twice a year. Download or request a free print copy of the newest edition!

Read newsletterRelated resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

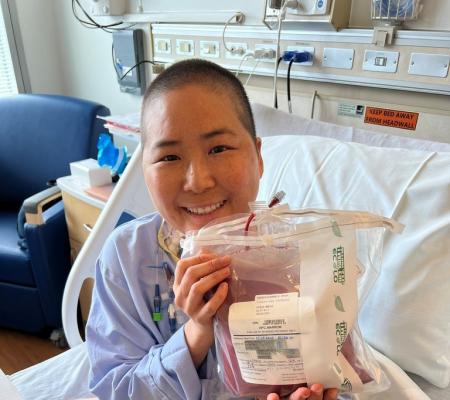

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309