-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Primary immunodeficiencies (PIs) are inherited disorders, which means that they run in families. As with other inherited conditions, knowing whether family members have a PI, a related condition, or symptoms of undiagnosed PI, can give you and your healthcare provider important context for your health. And if you’re already diagnosed with a PI, collecting your family’s medical history can help future generations understand their health.

Collecting family medical history

The first step in collecting a family medical history is sketching out a family tree. Start with the person who’s the focus of the history and map biological relationships out to third-degree relatives (e.g., first cousins, great-grandparents) if possible.

After drawing the family tree, collect information about the health of each identified relative and be as specific as possible for the information you collect. For example, if an aunt had cancer, you want to specify what type and stage of cancer, what age the person was when it was diagnosed, and the outcome.

There are several tools for collecting family medical history, including “Does it run in the family?” from the Genetic Alliance and “My Family Health Portrait” from the U.S. Surgeon General. There’s no guide or tool specific to PI, but here’s what is most important to capture if you suspect or want to document a family history of PI:

- Diagnoses of PI.

- Non-accidental infant or early childhood deaths.

- Relatives with a history of any of the following:

- Enlarged spleen, liver, or lymph nodes without a known cause.

- Low blood cell counts (e.g., neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia) either due to autoimmunity or without a known cause.

- Being considered “sickly,” or reoccurring, unusually severe (i.e., requiring hospitalization or IV antibiotics in an otherwise healthy person), or uncommon infections.

- Note whether these individuals had/have healthy siblings, as this can indicate that the infections were not a result of shared environment.

- Diagnoses of autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease (e.g., lupus, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease), particularly if diagnosed as a child.

- Cancer diagnoses, particularly blood cancers (leukemia, lymphoma).

Family medical history can reveal patterns

How does family medical history help in diagnosing PIs?

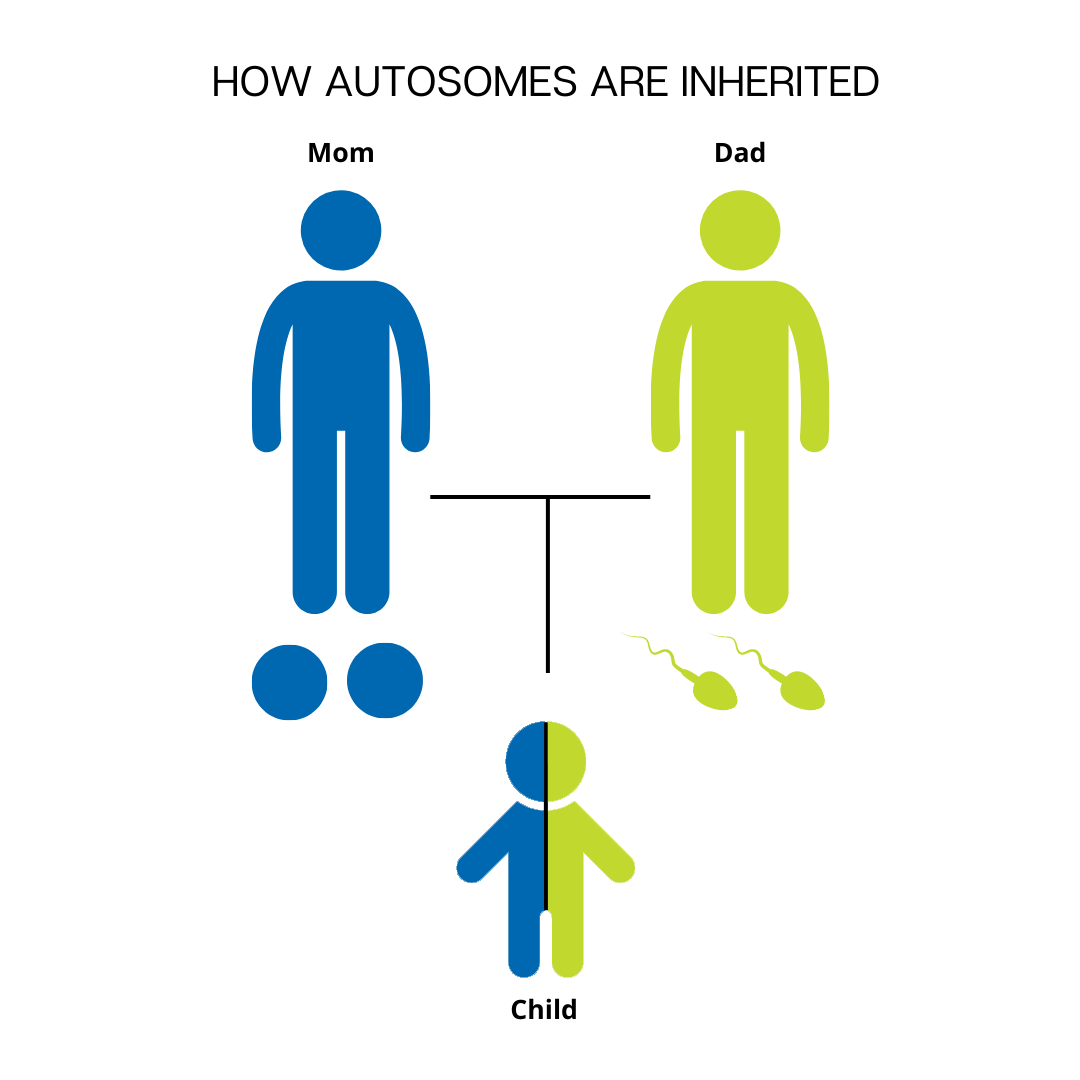

Many, but not all, PIs have a known genetic cause within a single gene (genetic variant) and show characteristic patterns in family medical history depending on how the genetic variant is inherited. There are three inheritance patterns for single-gene conditions: autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, and X-linked recessive.

Autosomal recessive means that an individual has to inherit two copies of the PI-causing genetic variant, one from each parent, in order to have the condition. ‘Autosomal’ means that the variant is not on a sex chromosome, so females and males have an equal chance of inheriting an autosomal recessive PI like adenosine deaminase (ADA) severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID).

PIs that are autosomal recessive are carried silently through the generations until someone who is a carrier—that is, who has one copy of the gene variant but does not have the PI itself—happens to have children with another carrier. Even then, a child of two carriers has a 25% chance of inheriting both copies of the variant and being affected by the condition. Unless there is intermarriage between people who are related, an autosomal recessive PI doesn’t show up in every generation and multiple individuals with the PI in the same family tend to be siblings.

Like autosomal recessive PIs, the genetic variant that causes an autosomal dominant PI is not on a sex chromosome, so females and males are equally likely to inherit the condition. The difference is that an individual only has to inherit one copy of the variant, which can come from either parent, in order to have the disorder. Warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome is an example of an autosomal dominant PI.

In a family medical history, an autosomal dominant PI can be traced through every generation and there are typically more family members with the disorder than in a family with an autosomal recessive PI.

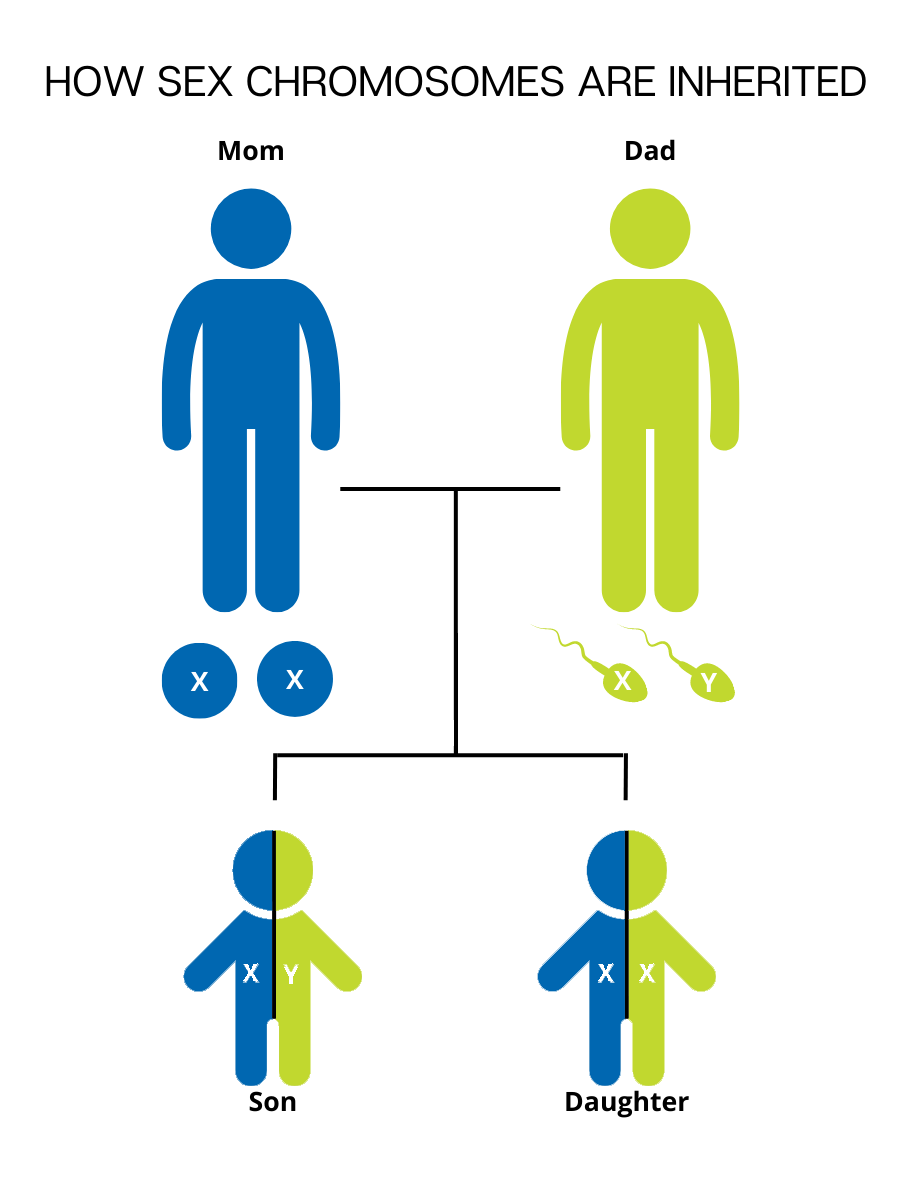

father. People who are genetically male have one copy of the X chromosome from their biological mother and one copy of the Y chromosome from their biological father.

X-linked recessive PIs like X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) are a bit different. X-linked means that the PI-causing genetic variant is located on the X chromosome, which is a sex chromosome. Like an autosomal recessive PI, anyone with two X chromosomes (genetically female) has to inherit two copies of the variant to be affected.

But males only inherit one X chromosome, from their mothers. Males that inherit a single copy of the X-linked genetic variant are affected because, unlike females, they do not have another functional copy of the gene in question. In a family medical history, X-linked recessive conditions show up more often in males and can be traced back through male relatives of an affected male’s mother, such as the maternal grandfather or maternal uncles. X-linked recessive PIs are never transferred from an affected male to his sons.

Unfortunately, experts don’t yet know the genetic cause (or causes) for some of the most common PIs, like common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and selective IgA deficiency (SIGAD). These disorders could be caused by a combination of genetic variants across multiple genes or a combination of environmental factors and genetic variants. The influence of multiple genes and/or non-genetic factors makes it more difficult to trace these conditions within a family. However, there is evidence that individuals with PIs that are not genetically defined are much more likely to have relatives with the same or similar disorders than the general public. So, even with disorders that have complex inheritance, a family medical history can be useful.

Family medical history has its limitations

Of course, family medical history is just one set of information and it isn’t always helpful in considering or diagnosing PI in a particular person.

For example, some PIs show what’s known as variable penetrance. That means that even for a disorder with a known cause in a single gene, people with the same variant in that gene don’t have the same severity of the disorder. A PI with variable penetrance can make it harder to trace within a family because less-severely affected individuals may not even suspect that they have a PI.

Also, genetic variants aren’t always inherited from parents. Sometimes, they happen spontaneously when an egg or sperm cell is formed, or early in fetal development. So, an individual with PI could have no family history of the disorder because they are the first person in their family to have the genetic variant that causes the disorder in all of their cells. In these cases, the PI does not show up in previous generations at all, although it is helpful to document for future generations.

Despite these limitations, family medical history can give healthcare providers crucial context and help them consider possibilities that they wouldn’t otherwise. Proactively collecting family medical history, not just for PI, but for other conditions as well, is worth the time and effort.

Topics

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.