Hospital stay and the transplant

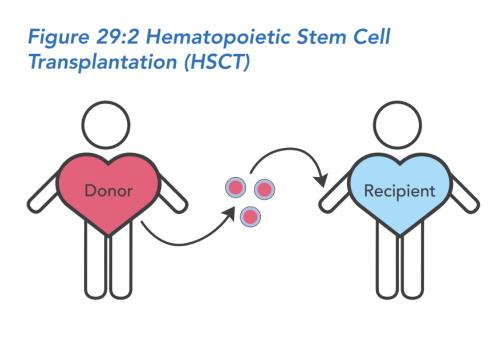

HSCT is different than organ transplants (e.g., liver, lung, or kidney) in several ways. The transplant itself is not a surgery, because the stem cells are given in a vein similar to a transfusion. Also, HSCT recipients need special preparation to receive the stem cells that solid organ patients don’t need. The process of replacing the stem cells in the bone marrow requires an inpatient stay of about six to eight weeks. This inpatient stay is what most people think of as 'the transplant.'

After discharge, full recovery of the immune system to a functioning immune system occurs as an outpatient and is a process that takes many months, up to a year. Unlike solid organ transplant recipients, HSCT recipients are able to wean off of immune suppressive medications if all goes well because the new immune system becomes accustomed or tolerant to the patient's body.

Central line

If the HSCT recipient is healthy enough to proceed with the transplant, they will receive a long-term (but ultimately temporary) IV line in a large vein in the chest or neck. This line is called a central line. The recipient will go under general anesthesia in order for the central line to be put in.

The central line helps doctors take blood from the recipient to monitor the progress of the new immune system. Doctors also use the line throughout the transplant process to administer chemotherapy, the donor cell infusion, antibiotic, antiviral, and antifungal medications to prevent infection, and IV fluids. It avoids the need for repeated IV placement and venipuncture. The recipient or a caregiver will need to learn to take care of the central line.

Conditioning

What happens during conditioning is similar to what happens before replanting a garden. If the HSCT recipient's immune system is a garden filled with weeds, the weeds may need to be cleared out before healthy plants can grow. For stem cell transplant, the conditioning regimen acts as weed killer. It is a combination of medications that destroy the recipient's own immune and stem cells to prepare for receiving the donor stem cells.

The goal of conditioning is to increase the chances of complete replacement of the recipient's immune system with donor cells and reduce the chance of treatment complications, such as failure to engraft and GVHD. On the other hand, the use of conditioning comes with side effects and the potential for serious risks of its own. Together, the recipient, their family, and their doctors should review the options available and decide whether to use conditioning based on the balance of benefits and risks.

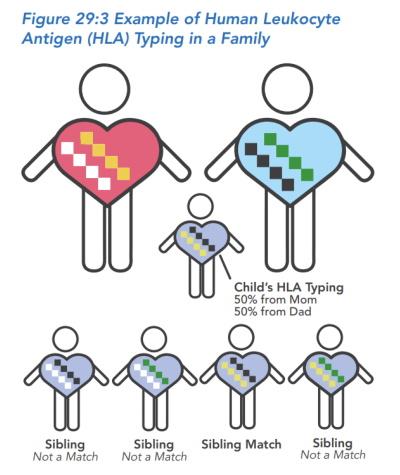

In general, conditioning may be recommended when the recipient has some immune function or when the stem cell donor is not related to the recipient. In general, conditioning may not be recommended when the donor is a fully matched sibling or the recipient has an active infection, is very young (under 2 months of age), or is small (e.g., was born prematurely). Conditioning is also not recommended when treating certain types of SCID that amplify the toxicity of conditioning drugs. However, when conditioning is not used, the chances of the recipient achieving a fully functioning immune system are generally lower. The recipient may need additional treatment, have more infections post-transplant, or even need another HSCT later in life.

A doctor may strongly recommend that conditioning be used or not used based on his or her best judgment and current research guidelines, the recipient’s specific situation, and sometimes the hospital’s standard practice. If conditioning is recommended, questions to ask the doctor include:

- What side effects may be most problematic?

- What are the risks of the specific conditioning regimen?

- Long term, do the potential benefits of conditioning outweigh the potential risks?

- For the recipient, is conditioning the best choice?

If conditioning is not recommended, questions to ask the doctor include:

- How likely is it that HSCT will lead to a fully functioning immune system?

- What are the chances that the recipient will need another transplant later in life or lifelong immunoglobulin replacement therapy?

- How likely is it that the recipient’s body will reject the transplant?

Types of conditioning regimens

There are two major categories of conditioning, drugs that target stem cells and drugs that target immune cells. They have different goals. HSCT recipients may have one or both types of conditioning before treatment.

Conditioning targeting stem cells uses chemotherapy drugs to reduce the number of stem cells in the recipient's bone marrow. Doctors call this myelosuppression. The goal is to make space in the recipient's bone marrow for the donor stem cells to engraft. There are several intensities of myelosuppressive conditioning. They use the same drugs, such as busulfan or melphalan, but vary in the dose and number of drugs used. The three categories of myelosuppressive conditioning include:

- Myeloablative conditioning (MAC): This type of conditioning uses a higher dose of chemotherapy drugs aimed at completely getting rid of the recipient’s stem cells. Successful MAC makes plenty of empty space in the recipient's bone marrow for new stem cells to land and grow. In general, MAC has the best chance to fully replace the bone marrow with new stem cells to achieve a fully functioning immune system that can fight off infections. However, this approach does not always work in every patient and comes with more severe side effects and higher risk.

- Reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC): This type of conditioning uses lower doses of chemotherapy drugs to achieve full replacement of the recipient's stem cells but with less toxicity. Successful RIC makes enough empty space for donor stem cells to land and grow. Use of RIC means less severe side effects and lower risk. But because RIC uses lower doses, there is a greater chance that replacement of the recipient's stem cells will be incomplete when compared with MAC. This means the recipient’s immune system might not be fully functioning after the transplant. For example, the recipient might still need lifelong immunoglobulin replacement treatment.

- Low-dose conditioning: This type of conditioning uses very low doses of chemotherapy drugs and is more commonly used in gene therapy.

Conditioning targeting immune cells uses drugs to reduce the T and B cells in the recipient’s immune system. Doctors call this immunosuppression. The goal is to protect the donor stem cells from being attacked by the recipient’s immune cells. There are two categories of immunosuppressive drugs:

- Antibody-based drugs: Antibody-based drugs, also called serotherapy, use antibodies to target the recipient’s immune cells with the goal of decreasing the risk of graft rejection. Examples include alemtuzumab and ATG (anti-thymocyte globulin).

- Chemotherapy drugs: Some chemotherapy drugs kill immune cells, but not stem cells. Examples include cyclophosphamide and fludarabine.

Conditioning side effects

Conditioning can have short-term side effects and long-term risks. Short-term side effects are temporary and usually subside when the treatment starts working. Long-term side effects may appear months or years after conditioning. In addition, some short-term side effects may become chronic and last a long time.

Short-term side effects may be mild to severe:

- Mucositis and nausea, vomiting, diarrhea: Chemotherapy can damage the lining of the mouth, throat, stomach, and intestines. This can be very mild or more problematic depending on the intensity of the conditioning regimen. Recipients may have sores, drooling, nausea, pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and sometimes bleeding. These side effects can be treated with pain medications, anti-nausea medications, and nutrition and fluid support such as a feeding tube.

- Anemia, bleeding, and infection: Conditioning will reduce the number of all of the recipient’s blood cells, including immune cells, red blood cells, and platelets, for several weeks. During this time, the recipient is at an increased risk for infection, may have blood clotting problems, or may feel tired and weak because they have fewer red blood cells.

- Vital organs, such as the brain, lungs, kidneys, and liver, may be harmed. Sometimes these complications can be treated with medication.

Any one of these long-term complications is infrequent, but recipients and their families should know that they do sometimes occur:

- Chronic problems from harm to vital organs, such as the brain, lungs, kidney, and liver. Sometimes these complications can be treated with medication.

- Bone growth suppression, which may result in shortened stature as an adult.

- Endocrine abnormalities, such as growth hormone deficiency, hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid), and ovarian and testicular dysfunction.

- Reduced fertility.

- Increased risk of cancer.

- Developmental delay or problems with learning.

- Issues with the development and arrangement of teeth.

Stem cell infusion

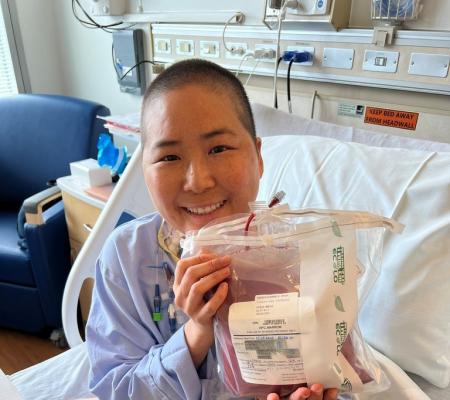

Once a donor is found, the timing of the transplant must be arranged so that the donor cells are ready when the recipient has completed conditioning and is ready to receive them. The planned day of stem cell infusion is called Day 0. Stem cells are given through the central line like a blood transfusion. Similar to a blood transfusion, the stem cell transplant is a minor procedure that can take as short as 30 minutes or as long as a few hours. General anesthesia is not necessary and caregivers may be present during the procedure.

After Day 0, recipients typically remain in the hospital for several weeks while doctors wait for the new stem cells to grow. In the garden analogy, once the weeds are gone and the seeds are planted, there is a period of time when the garden is empty because it takes time for the healthy plants to grow. During this time, there are no blood cells being produced by the bone marrow, so it is common for the recipient to need blood and/or platelet transfusions.

Recipients are watched closely for any signs of infection, and they may need pain medicines, medicines for nausea, and fluid and nutrition support. Frequent blood tests are performed to monitor for any signs of organ dysfunction. Most recipients also receive medications that suppress the immune system in order to help prevent GVHD. Common examples include cyclosporine or tacrolimus.

Engraftment

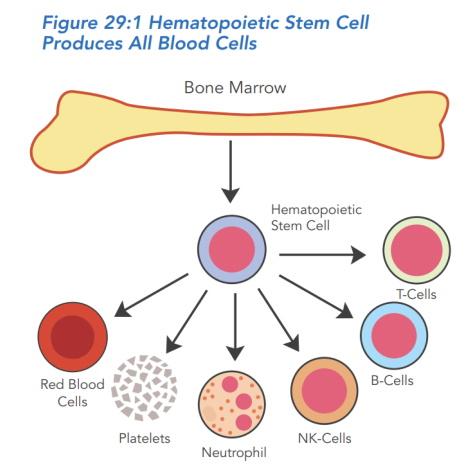

After an HSCT, doctors expect engraftment to occur. Engraftment is when the donor's hematopoietic stem cells grow in the recipient and start making healthy blood cells. Transplant teams monitor the recipient with a blood test called a complete blood count (CBC). When the stem cells start to work, the numbers of particular blood cells will start to rise.

The anticipated time it takes for different cell types to recover to a safe level varies. Until doctors are sure that there is good engraftment, the recipient will be monitored very closely. Sometimes the recipient is given medication to jumpstart white blood cell production specifically.

Once there are signs of engraftment, a special blood test will be done to determine what percentage of blood cells are from the donor, called an engraftment or chimerism study. Chimerism refers to having cells in the body with different genes, in this case, hematopoietic stem cells and blood cells with the donor's genes and all other cells with the recipient’s genes. The higher the percentage of blood cells with the donor’s genes, the better the HSCT has worked.

Once the blood counts recover to a safe level, recipients may be able to transition to outpatient care at the transplant center. Recipients will have a lot of oral medications, and many need some IV medications, IV fluids, or IV nutrition during the early outpatient treatment phase. Home healthcare services, depending upon an individual's insurance coverage, may help with these needs.