-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

In a recently published paper in Nature Medicine, French and British researchers present encouraging data on the long-term outcomes of gene therapy to treat severe Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS). Following eight patients for a minimum of four years (and up to nine years) after treatment, Magnani et al. found that gene-corrected cells engrafted stably, and there were no severe adverse effects related to the treatment.

Even more promising, though, are the data related to patients' immune systems and WAS symptoms. Not only has the gene therapy proved safe, but patients experienced a significant and stable reduction in their symptoms, including infections, eczema, autoimmunity, and bleeding episodes, years after treatment.

How does gene therapy for WAS work?

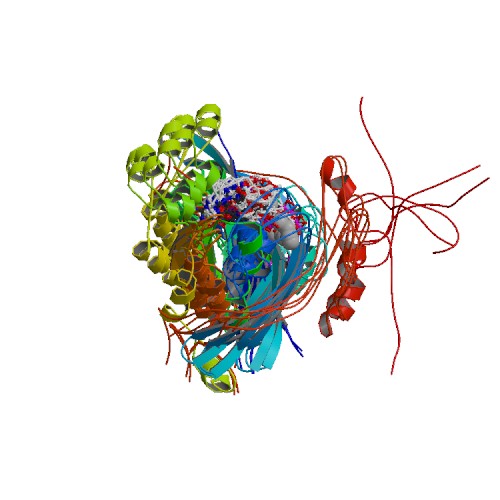

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS). View source.

People with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome have mutations in the WAS gene on the X chromosome, which codes for the WASp protein. WASp is made in all of the cells that give rise to white blood cells and platelets, as well as in white blood cells and platelets themselves. It is crucial for maintaining stable numbers of these cells and helps them respond to immune system signals — whether that means moving to the site of infection, activating another cell type, or releasing more signaling molecules. In WAS, mutations result in either little-to-no WASp protein or WASp with little-to-no function. As a result, people with WAS experience severe and frequent infections, spontaneous bleeding due to lack of platelets, eczema, autoimmune conditions like vasculitis, and an increased rate of blood cancers.

Gene therapy for WAS is similar in concept to stem cell transplantation (also known as bone marrow transplantation), the current WAS treatment of choice, provided a matching donor is available. In both cases, the idea is to replace the patient's mutant blood stem cells with cells that have a functional copy of the WAS gene. These new cells then give rise to a fully functional array of hematopoietic cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

For WAS gene therapy, the patient's own hematopoietic stem cells are collected and exposed to a genetically engineered lentivirus in which the virus' genes have been replaced by a non-mutated, fully functional copy of the WAS gene. These gene-corrected stem cells are then reinfused into the patient, where they migrate to the bone marrow, engraft, and start producing functional WASp.

But, providing a functional copy of a gene to patients with genetic disorders does not always eliminate their clinical symptoms, especially if there is tissue or organ damage that cannot be undone. And gene therapy comes with its own risks, namely the unintended disruption of other genes, leading to leukemia months or years after treatment.

What was the clinical outcome of WAS gene therapy?

Magnani et al. followed eight patients for 4-9 years after gene therapy treatment, including one patient who received treatment as a teenager and one who received treatment as an adult. Remarkably, the researchers showed that all eight patients produced T and B cell populations on par for their age after gene therapy. These cell populations are stable; to date, five of the eight patients have been able to discontinue antimicrobial therapy and IgG replacement therapy.

Clinically, the severity and frequency of patients' infections dropped. Eczema also resolved in seven of the eight patients, with the eighth experiencing much milder symptoms. Although patients' platelet counts remained lower than normal after treatment, they have not experienced any spontaneous bleeding episodes. Finally, patients' levels of autoantibodies dropped after treatment and their associated symptoms lessened.

Said senior author Dr. Marina Cavazzana, "The clinical results are very promising in the light of the age and severity of the treated patients."

One of the most concerning adverse events in early gene therapy trials was the development of leukemia in some patients after treatment. Scientists found that these cancers developed because the gene therapy viral vector inserted itself into problematic areas of cells' DNA, leading to the disruption of other genes. Magnani et al. showed that the gene therapy construct used for WAS was inserted stably (i.e., did not jump around or expand) in all patients and did not cause worrisome cell expansion (which can be a precursor to cancer).

That's why Magnani et al.'s long-term study of recipients of WAS gene therapy is such good news for both patients with WAS and the field of gene therapy.

What's next?

Another group of researchers in Italy and the United Kingdom released clinical trial data using the same lentiviral gene therapy construct to treat severe WAS in 2019. That study showed similarly encouraging immune system reconstitution and resolution of clinical symptoms, but at a shorter interval after treatment. Together, both studies demonstrate the promise of this therapy for treating WAS without the need for a bone marrow match.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309