-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

This SCID Compass blog post is part of IDF’s Stories Project, designed to provide a venue for those living with PI to share their experiences. Some are first-person accounts; others are written by IDF staff. If you have a story you’d like to share, email us at stories@primaryimmune.org.

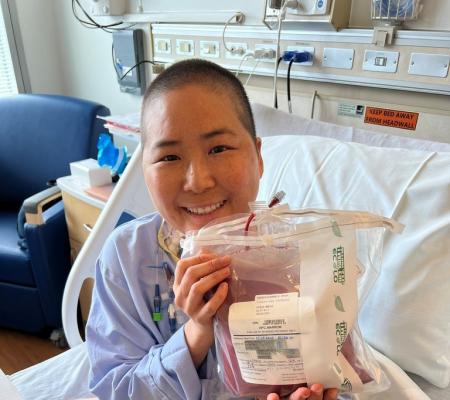

In this Stories Project blog, Maria Hope Diaz and her mother Felicita Diaz share the story of Maria’s journey with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID).

Maria Hope Diaz has a rare type of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), so rare that less than ten people in the world share the same condition. Maria’s diagnosis is SCID secondary DNA – PKcs, and it’s a primary immunodeficiency that almost claimed her life as a baby.

Maria Hope Diaz was “born beautifully” at Guam Memorial Hospital on December 7, 2005, said her mother Felicita Diaz, and she appeared very healthy. But at her first wellness check a week later, the newborn dropped from 6 pounds, 11 ounces to 6 pounds, 4 ounces. Felicita, then 33, thought maybe her inexperience as a mother caused the weight loss.

“I was a nervous wreck that I didn’t know what I was doing,” said Felicita.

As the months passed and Felicita returned to work, Maria transitioned to a nursery setting. Other health problems began to arise. Failure to gain weight. Constipation. A runny nose. By month five, Maria developed a fever, rash, diarrhea, and vomiting.

“We took her to the doctor, and it was then that they said she was dehydrated. We needed to get her admitted to the hospital,” said Felicita.

The medical intervention did little to help Maria, who developed a respiratory infection. Doctors administered Intravenous antibiotics to no avail. Maria required a feeding tube, and after becoming cyanotic (turning a bluish color due to lack of oxygen), she entered the intensive care unit.

“The doctors said, ‘Something is not right with your child. She is not responding to antibiotics. Either she has cystic fibrosis or an immune deficiency,’” said Felicita.

Further tests revealed Maria had parainfluenza type 3, or HPIV-3, a virus that causes bronchitis and pneumonia. Those with weakened immune systems can be particularly vulnerable to HPIV-3.

By mid-June, doctors told the family that Maria needed to leave Guam for better care. Otherwise, she would not survive.

“My husband and I were in the room with my sister-in-law and parents, and we all broke down,” said Felicita. “The doctors said, ‘We can’t do anything. Your child is going to die.’ I said, ‘That’s unacceptable.’”

The family ruled out traveling to Honolulu for medical care because the flight lasted about seven hours. Instead, they settled on the Philippines, a three and half hour flight. On a ventilator in ICU, Maria had grown too big for transport in an incubator aboard a plane. A doctor and respiratory therapist kept her alive on the flight by operating a manual ventilator.

When their plane left the ground, Felicita had no idea that Maria’s medical journey had only just begun. Mother and daughter wouldn’t return to live in Guam until four years later.

Seeking treatment

A few weeks after Felicita and Maria had settled into St. Luke’s Medical Center in Quezon City, Philippines, doctors diagnosed Maria with SCID.

“It was a big relief. The situation was she was going to need a transplant,” said Felicita.

St. Luke’s doctors stabilized Maria and transitioned her from the ventilator to oxygen on July 4. Meanwhile, Felicita contacted SCID specialists in the United States – including Dr. Rebecca Buckley and Dr. Mort Cowan – and made plans for the transplant.

Maria and Felicita left Manila for the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital on November 9. Once there, when Dr. Cowan learned Maria had HPIV-3, he wasn’t surprised.

“Dr. Cowan said, ‘There you go. That’s typical SCID,’” said Felicita.

On December 7, 2006, her birthday, Maria underwent her transplant at UCSF with her mother serving as her donor. Complications – including graft versus host disease – arose shortly after the transplant. Maria struggled with gastrointestinal problems and developed autoimmune hemolytic anemia, which caused the B cells to attack her organs.

Doctors treated Maria with heavy doses of steroids and prophylaxis and eventually administered chemotherapy to reduce the B cells. Despite her struggle with the transplantation side effects, Maria learned to walk and talk with the aid of occupational, speech, and physical therapy.

All the while, the months slipped by. It became clear that mother and daughter would not return home to Guam during Maria’s toddler years. The pair lived at Family House – a nonprofit that offers housing to families of families with cancer and other life-threatening illnesses – and in September 2007, they transitioned to an apartment in San Mateo, California, where they could easily travel to UCSF for appointments.

Maria’s grandparents flew to the United States to help Felicita with Maria, who remained in isolation at the apartment. Her grandparents shopped for groceries and medicine, cooked and cleaned. That allowed Felicita time to draw Maria’s blood for lab work, change end caps on her Broviac (a surgically placed intravenous line in the chest), maintain her feeding tube, and focus on Maria’s overall development and care. While chemotherapy and steroids had brought the GVHD and autoimmune hemolytic anemia under control, Maria remained on the other medications and required extensive care.

“You’re in emotional overdrive. It was stressful, but I had my parents there to take care of me. My job was to fight for Maria and develop relationships with the doctors. That’s the only way I knew how. I missed my husband. Living apart was sad. But you can only let emotions go so far,” said Felicita, who added that Maria’s father Frances Diaz, a union representative, visited when he could.

“You’re in emotional overdrive to live and do your best for your child. She is a gift, and until the Lord calls her home, it’s your responsibility to take care of her.”

Meeting family in Guam

Maria’s health slowly improved. Doctors reduced her medications but continued her immunoglobulin infusions and therapies.

In the spring of 2009, doctors allowed Felicita to take Maria home to Guam for Easter. The three and-half-year-old Maria met her extended family for the first time. She greeted them with big smiles, but Maria was overwhelmed with the new faces and loud voices, and wouldn’t venture past the sliding glass doors of her home to the outside where the big family gathered.

“She rarely walked out of the house. She’d never seen anything like it. She was afraid,” recalled Felicita.

After two weeks, Maria and Felicita returned to California. Treatment had restored Maria’s T cells, but the GVHD left her with no B cells. She continued with subcutaneous IVIG.

Finally, in July 2010, doctors cleared her to move back to Guam full-time.

Maria adjusted to life in Guam, attending elementary school and welcoming the arrival of her little brother, Antonio, in 2012.

Maria remained healthy during those years, save for the occasional cold or fever. To monitor her health, she underwent monthly, and sometimes bi-monthly blood draws and traveled back to UCSF twice a year for check-ups.

She didn’t discuss SCID with her classmates except when they asked about the gastrointestinal tube she maintained for extra nutrition. Maria explained that she needed it to live.

“At the age of 12 was when I fully understood my condition, the severity in the past that I suffered, as well as the effects of my rare genetic condition,” said Maria.

In 2014, the family received a call from SCID specialist Dr. Jennifer Puck who shared the news that researchers finally discovered the gene responsible for Maria’s SCID and that Felicita and Frances Diaz both carry the gene – PRKDC.

Making lifelong friends

In summer 2018, Maria traveled back to the United States to participate in a clinical trial to restore her B cells. In the anti-c-Kit trial, Maria received a boost of her mother’s stem cells, but instead of using chemotherapy to make room for the new cells, doctors used monoclonal antibodies.

Once again, Maria developed autoimmune hemolytic anemia after the treatment because of a T cell dysregulation. Steroids helped control the anemia, but the recovery time meant that Maria missed her entire last year of middle school. Still, Maria made memories and friendships at the Family House that sustain her to this day.

“I met numerous patients and their families and befriended them at the Family House. To them, I was like a big sister because when their parents and mine would go somewhere to run errands, I would be the one to babysit and hang out with them,” said Maria, recalling sleepovers and late-night monopoly games.

“They looked up to me because, during my highs and lows, I made my best efforts to maintain a positive attitude and spread small acts of kindness towards the families I knew, as well as the staff and incoming volunteers.”

Some friends Maria knew at the Family House passed away due to their illnesses.

“This made me feel sad because when I stayed at Family House, I would reminisce about the memories we had as a family on the 5th floor. We were known as the ‘5th Floor Tribe’ because we always stood by each other and treated everyone like family, like they belonged to an elated community,” said Maria, who keeps in touch with some Family House friends through social media.

Today, two years after her second treatment, Maria is living back home in Guam and doing well. She has engrafted T and B cells, and she is waiting to see if the B cells produce IgA or IgE. The 15-year-old sophomore travels back to California in July for a re-check on her B cells.

Maria tries to keep SCID in the background of her life, but sometimes people will inquire about her short stature (caused by the chemotherapy) or worry that she’ll get sick if she socializes with them. To help her cope, she enjoys journaling, biking, swimming at the beach, creating TikTok videos, hanging with friends, and having sleepovers with her cousins.

Experiences with medical staff and fellow patients have inspired Maria to pursue a career in medicine. She is considering a slew of possible roles – nurse anesthetist, pediatric surgeon, licensed practical nurse, OB-GYN, pediatric infusion nurse, and pediatric oncology nurse.

Maria is hopeful about the future and encourages others coping with SCID to keep a positive mindset.

“Religious or not, turn to prayer and ask God to physically, spiritually, emotionally, and mentally heal you and walk beside you throughout your SCID journey. That is what I do, and God has blessed me and my family with unexplainable miracles,” said Maria.

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.