-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Mathilda von Guttenberg studies neuroscience with a specialization in psychoneuroimmunology. Psychoneuroimmunology may seem like a complicated term, but the subject matter is simple when von Guttenberg explains it. She said psychoneuroimmunology helps explain questions like: What is the connection between a person’s physical and mental health? How does the mind affect the body, and how does the body affect the mind?

“Psychoneuroimmunology is the centerpiece where the mind-body connection influences so much, and for people living with long-term conditions, it’s not just the physiological, it’s the psychological,” said von Guttenberg.

“There’s a molecular and actual scientific connection between the mind and the body, where one can worsen the other and the other way around. I wanted to position myself in the middle of that and figure out a way where I could create the biggest difference.”

Von Guttenberg, 22, is a senior at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) majoring in neuroscience, but the idea of building a biomedical career took shape a decade before when doctors diagnosed her with common variable immune deficiency (CVID).

Respiratory infections and gastrointestinal issues kept von Guttenberg constantly ill and on antibiotics as a child and compelled von Guttenberg’s mother to take her to countless specialists for answers. For years, clinicians remained perplexed by von Guttenberg’s symptoms.

“I was just stamped as an unlucky kid,” said von Guttenberg.

Even when doctors dismissed her health issues as “phantom symptoms,” von Guttenberg said her mother never gave up trying to get a diagnosis. That advocacy paid off and the family finally found an immunologist who discovered von Guttenberg had CVID.

Subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) replacement therapy provided some relief from infection but caused side effects like headaches and joint inflammation. After five years, von Guttenberg switched to a different product with lower concentration of immunoglobulin G, which alleviated the reactions.

Throughout her middle and high school years, von Guttenberg remained vigilant about her health. She missed school a lot and didn’t socialize much with her peers.

“Taking care of my body was something I had to worry about from a much younger age. I think living with a chronic condition through school is incredibly difficult,” said von Guttenberg.

Von Guttenberg spent her teen years learning as much as she could about her condition.

“I was always forced to connect the dots that the doctors wouldn't and answer my own questions to a certain extent,” said von Guttenberg. “I wanted to know the science behind it. As I got older through middle and high school I fell in love with subjects like biology and chemistry, and they were subjects I was always good at. So, I started looking to see how I could put this to good use.”

In 10th grade, she decided to focus on career opportunities in the medical field when she couldn’t find much research on either CVID or primary immunodeficiency (PI).

“It was a combination of frustration with the lack of knowledge, particularly obvious in how long it took to diagnose me, and then also the hope to help other people in a similar situation,” said von Guttenberg.

The years of grappling with repeated illnesses and uncertainty instilled a deep curiosity about how psychological and biological factors shape health outcomes, said Guttenberg. At UCLA, she channeled her curiosity into neuroscience and psychoneuroimmunology research.

Von Guttenberg describes the field of psychoneuroimmunology as “an attempt to decipher the bidirectional communication between the brain and the body” that can be examined on a molecular level or from the clinical psychology perspective.

As an example, on a molecular level, researchers can study how immune dysregulation affects a person’s mental health downstream by measuring stress levels. Or they can delve into the same subject via clinical psychology and examine how to intervene to prevent immune dysregulation from negatively affecting people’s mental health and causing depression.

Part of von Guttenberg’s research at UCLA involved another mind-body connection, namely how the gastrointestinal system (or gut), which contains most of the body’s immune system, and the brain interact.

Von Guttenberg is currently examining how living with a long-term health condition affects mental health and how providing intervention for psychological symptoms affects physical health.

“We talk about it in terms of the body mindset. How does your relationship to your condition, to your symptoms affect your actual physical condition and how does that display in blood markers, immune markers, etcetera?” said von Guttenberg.

“I do believe that there is a big connection there, even from personal experience. I struggled with mental health through the years as a teenager. I know a lot of that had to do with not only living with a chronic condition but also having a dysregulated immune system.”

Gutenberg is currently applying for PhD programs in psychoneuroimmunology.

“My focus has since evolved to explore how stress, resilience, and biopsychosocial dynamics impact mental health in populations with chronic conditions. I began asking questions like: What shapes our capacity to adapt in the face of adversity? What factors allow some to navigate health challenges more effectively than others?" said Guttenberg.

“Specifically, I aim to investigate how mindsets about the body influence physical and psychological functioning in individuals with chronic illnesses, particularly immune conditions. This research bridges the gap between the psychological and physiological domains, with the goal of designing targeted interventions that improve well-being and long-term health outcomes for this population.”

When she’s not doing research, applying for PhD programs, taking classes, and working, von Guttenberg relieves her stress by being outdoors and reconnecting with nature through hiking, skiing, swimming, and horseback riding, a passion of hers since childhood.

“I got very lucky having family in Switzerland and having the opportunity to go to the mountains when I go back home and do a lot of the things that I love,” said von Guttenberg, a German native who lived in the United States for half of her childhood.

Von Guttenberg discovered IDF while researching her condition and appreciated a centralized platform where she had access to the latest research and PI specialists.

“It gave me a sense of hope that there is a group of people out there who are respectful of the cause, raise awareness, and are knowledgeable on the topic, because I didn't receive that kind of support through anything else,” said von Guttenberg.

“I think one of the most difficult things about immune deficiencies is that they're very unnoticeable. Most of us, if we're undergoing treatment, we look healthy. We look like healthy young people. And the difficulty that kids deal with especially is that the condition goes unnoticed.

“Having a community of people that know what’s going on and understand and make you feel seen and heard is really powerful—and really special.”

While SCIG helps stave off infections, said von Guttenberg, mindset plays a big role in improving her health. Living with CVID made her resilient and knowing more about the condition set her on a path to empowerment and a fulfilling profession.

“I understand my condition and I’ve learned how to cope with it and deal with it and not always put it in a negative light, because I understand all of the amazing things that have blossomed from it,” she said.

Read other newsletter articles

The IDF ADVOCATE is the national newsletter of the Immune Deficiency Foundation, published twice a year. Download or request a free print copy of the newest edition!

Read newsletterRelated resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

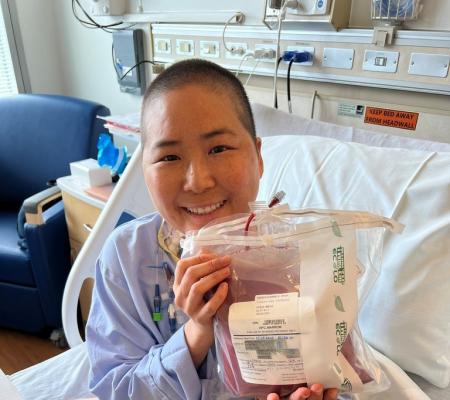

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309