-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Caitlin BenVau lived in a remote Texas desert for five years where she tested rocket engines for a company that plans to fly a spacecraft to the moon. She and her team measured how the engine operated under certain conditions like extreme heat that could cause it to explode.

“You don’t want that to happen when you’re flying, so you have to do all these intensive tests on the ground. We are trying to trick the rocket engine into thinking it was flying by connecting it to a permanent structure that would not move but would be able to hold the force of it being tested and create all the other conditions that the rocket engine would experience when it’s on the rocket, so we can predict what it would do when it’s in space. Our goal was to certify it ready to fly,” explained BenVau, a test engineer and test director.

BenVau, 27, is diagnosed with common variable immune deficiency (CVID) and while the condition didn’t directly influence her decision to become a rocket scientist, it certainly shaped her personality.

“I think having primary immunodeficiency (PI) has made me a much cooler person and a much more fun person. I think that everyone I talk to ends up knowing about it in some way and my goal is to try to get people to be more conscious, in general, about not only the difficulties that others are going through but about health concerns,” said BenVau.

“Having PI makes me much more empathetic and attentive to other people. I’m able to connect with people from across the spectrum who’ve handled things that are outside of what we normally talk about like family tragedies or anything that you are going through. I just think it makes you a very kind and warm person.”

BenVau’s journey to diagnosis began with a bug bite on her leg when she was 12. Overnight, the red mark turned her thigh black, with red spreading to her torso and knee. The emergency room clinicians diagnosed a brown recluse spider bite. She had surgery to remove the skin that left a hole bigger than a golf ball in her leg.

“The doctors thought the infection was a one-off,” said BenVau.

As she recovered and used crutches to help her walk, BenVau got a second bite, this time from a mosquito. Again, she developed a life-threatening bacterial skin infection that required surgery. This time, clinicians ran tests and found BenVau had extremely low immunoglobulin G (IgG) and an IgA deficiency, leading to a CVID diagnosis at age 13.

Doctors prescribed treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy, but BenVau continued to have recurrent infections, especially sinusitis.

“It was discussed whether or not I should go to college because of the increased risk of becoming sick and being away from my family and the medical team,” she said.

BenVau had no intention of not attending college, and throughout high school, her love of science blossomed. She grew from a child playing with Legos, Erector sets, and chain reaction contraptions to a teenager attending engineering summer programs on university campuses.

Along with her academic pursuits, BenVau established a social network for her classmates with medical challenges to come together, talk to each other, and give presentations. The club, Defying Disorders in High School, welcomed students coping with physical or mental health challenges.

“It felt like it was difficult if you were going through something medically to talk to other kids your age. The point was to be a centralized location where if you were dealing with something heavy like cancer or diabetes it would be a way to make friends that could understand and could help build your confidence,” said BenVau.

“I would do stuff like give templates on how to talk to your teachers about difficulties you’ve been having, and it was a way to let others in the group know that you are worth it, you deserve to go to school, and you deserve to have friends.”

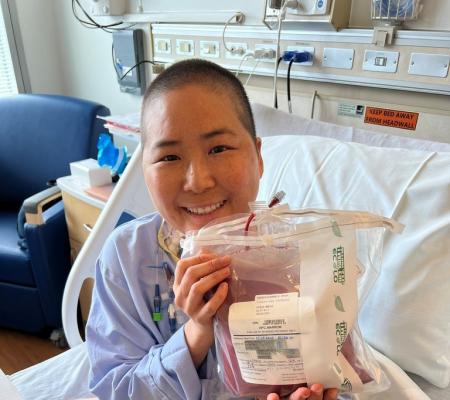

While earning her degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, BenVau continued to build community among those sharing health challenges by organizing educational events. She also surrounded herself with a supportive social network, inviting friends to her dorm on infusion nights to help her with subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) replacement therapy, a treatment she switched to in college.

“My friends would come over and we’d pick out a movie and they’d help me infuse. Everyone knew how to load the syringe,” said BenVau.

Today, she coordinates a company resource group, funded by her employer, that offers speakers and networking for those with mental health and physical challenges, and she performs outreach at job fairs for people with disabilities.

“That’s really important to me,” said BenVau.

Living in the desert two hours from the nearest town, BenVau and her co-workers grew close. When she and her husband (also employed by the space technology company) got married, so many people from the company attended her wedding that they closed the testing site for a day. She wants other young people to know that having a PI is nothing they need to hide. Embrace those who accept you and move on from those who don’t, advises BenVau.

“It’s been a journey to find friends, but I think when I found friends, they’ve been for life, and they’ve been incredible,” she said.

A few months ago, BenVau finished testing the rocket engine in Texas and moved to the Seattle area where she is working on the lunar landing phase of the project. Enthusiastic about her job and proud of the scientific progress she’s contributing to, BenVau urges other young people with PI not to let the condition stand in the way of what they want to achieve.

“There have been so many advances in medication, you can still have any career you want. There are a lot more opportunities than what it may seem like at first. It probably didn’t seem like I could live so remotely but I did. You’d be surprised—if you understand yourself and know those limits, if you’re kind to yourself, to your body, and to your health, and you are paying attention, you can still do really fun things,” said BenVau.

“The same with a college degree. I was up most nights doing homework, in lectures late and it was really intensive but I was able to do it because I was respectful of my body. I understood my limitations. It didn’t make me any less of an engineer than the person next to me, and it doesn’t make me less capable in my career, it just means I have to be more patient with myself.”

She wants her peers to know that PI and the health challenges associated with the condition don’t have to limit what they can do in life.

“I wasn’t born thinking I wanted to work on rocket engines, but I thought it was interesting, and having PI didn’t make it so that I couldn’t do it. I just had to be smart about it.”

Read other newsletter articles

The IDF ADVOCATE is the national newsletter of the Immune Deficiency Foundation, published twice a year. Download or request a free print copy of the newest edition!

Read newsletterRelated resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309