-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

When he was an undergraduate student earning a degree in medical physics, Hayden Scott sat in the lobby of the Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center, waiting for his research supervisor. Scott planned to spend the day checking the operations of a computerized tomography (CT) scanner. The 30-minute wait allowed him to ponder more than the day ahead of him.

He recalled being 10 years old and in the center with a sinus infection so severe that it threatened to spread to his brain stem. He thought of the priest who visited him and the doctor who brought him a felt Hero Hat, a special memento for kids with cancer and other critical illnesses.

“I was inpatient enough to know what it was like and what the expectations were. I noticed everyone was a little bit kinder than normal, and they offered me ice cream. The expectation was that I was terminal, and I was likely not going to survive,” said Scott.

Antibiotics, steroids, and sinus surgery allowed Scott to survive the infection, and more than a decade later, the significance of being in the same hospital where he’d spent so much time as a child flooded him with emotion.

“Being back in the center was for me a rewarding experience, but I remember the feeling, like the gravity in the room had increased. To be back and know that I'm here doing something for other patients as opposed to just being a patient, for me, was a full-circle moment,” said Scott.

“I still have the Hero Hat the surgeon gave me. I find it my most prized possession, and it describes a standard of care that has directed me, and I think I’ve carried a lot of those decisions with me moving forward.”

Scott, now 27 and pursuing a PhD, spent his childhood chronically ill with respiratory and staph infections. Living in a medically underserved community in Louisiana, he and his parents traveled close to an hour to the nearest hospital for stays, about once a year.

After being diagnosed with IgG subclass deficiency, he began intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy in third grade, along with injections of Xolair for his persistent asthma. He missed so much school that his parents considered homeschooling him, but the treatment improved his respiratory condition and stabilized his health.

“For a long time, it was kind of rocky, given the amount of time I had missed, though looking back, the way I experienced education helped establish this sense of internal purpose or my own internal clock, where I was not comparing myself to others, and I did things at the interest and pace I set for myself,” said Scott.

“I understood my own criteria for success, and I think I’ve carried this approach with me, where I’m not nearly as stressed as a lot of my colleagues.”

In high school, he experienced his first multi-year period with no infections. Along with good health came an opportunity to attend a public boarding school. There, Scott met a teacher with a PhD in nuclear physics who taught an elective on medical physics. That’s when Scott realized he could build a career in the medical field without working directly with patients and risking infection.

A medical physicist collaborates with a radiation oncologist to treat patients with cancer. The medical physicist uses physics and math to develop and manage radiation treatments. They decide how much radiation to use, the angle it should be delivered, and how to tune the beam so that the radiation is deposited with millimeter accuracy.

“Delivering radiation is an incredibly challenging process,” said Scott, who explained that radiation is applied to a mannequin of the patient first.

“There's an imaging side to it where the interpretation of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT scans is done by radiologists, but the actual calculations and algorithms, and mathematical reconstruction of these images, are done by the physicists.”

The medical physicists calibrate the radiation machines for both individual patients and for the patient population as a whole. The pressure of the job can be intense.

“If a surgeon does a bad surgery, one patient suffers, but if a radiation machine is miscalibrated, then every single patient that gets put on that machine is mistreated. That’s the kind of work we do,” said Scott, who sits with other medical staff in the control room when a patient is being treated. “It's about as clinical as I could ever have imagined without direct one-on-one patient interaction.”

Research is consistently at the center of Scott’s educational and professional journey. As an undergraduate at Louisiana State University, he helped create three-dimensional mesh masks as immobilizers for patients receiving radiation in the head or neck area. At the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, he developed techniques to measure radiation dose and location using detection devices placed on patients.

“I came here with the distinct goal of getting my master's and going to residency because I wanted the most direct pathway to working in the clinic. And it took me about two weeks to realize I would want to stay around here for a PhD, because this institution is so incredible,” said Scott.

Even though Scott doesn’t work directly with patients, he is satisfied knowing that he is making a great contribution to their treatment and keeping them safe in an environment that can have risks.

“I have this immense sense of purpose of being in the clinic, and this was the driver of my coming to this program and doing this profession, which is that I understand the value and weight of the service. So, whether or not I see the patients is not as important as knowing about them,” said Scott.

Scott’s PhD research focuses on developing safety protocols for clinical trials for ultra-high dose rate radiotherapy. In this type of radiotherapy, an entire dose that usually takes 20 minutes can be delivered within one second.

“The outcomes are better, and we don't know why,” said Scott.

Scott specializes in pediatrics and is inspired by the clinicians he works with, especially a radiation oncologist he shadows who plays patients’ favorite songs on the ukulele when they are finished with treatment. He is considering earning a medical degree to become a pediatric radiation oncologist after his PhD in medical physics, even though he’ll be in his mid-30s before completing his education.

“Every [person with an] MD/PhD I talk to, I ask the question, do you think that these extra four to seven years of training lead to a meaningfully different service that you can provide as an MD/PhD physician as opposed to just like a PhD medical physicist? Every single one of them says yes, because you get to talk to patients. You get to be the person that they interface with. It's cancer care. You get to be the person that they're weeping to. You get to be the person who celebrates their end of therapy. You get to be the person who helps them through the end of life. They say that it’s worth it,” said Scott.

Scott’s health remains steady, but he knows he could be one infection away from having to go back on IVIG. He’s also experienced side effects from the years of steroids. When he broke a rib playing basketball, a scan revealed he has osteoporosis, and treatment with steroids is no longer an option if he gets ill.

After learning a friend also has PI by reading her story through the Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF), Scott delved deeper into IDF’s resources and appreciates knowing that he is part of a greater community.

“I think the advocacy that's done with IDF is inspiring because, for me specifically, it has deepened my connections,” said Scott.

2026 PI Conference

Join us June 25-27, 2026, in San Antonio, Texas, for a transformative experience where stories connect, voices unite, and journeys inspire. No matter where you are in your primary immunodeficiency journey, access expert-led education, meaningful connections, and cutting-edge insights from world-renowned immunologists.

Register nowRelated resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

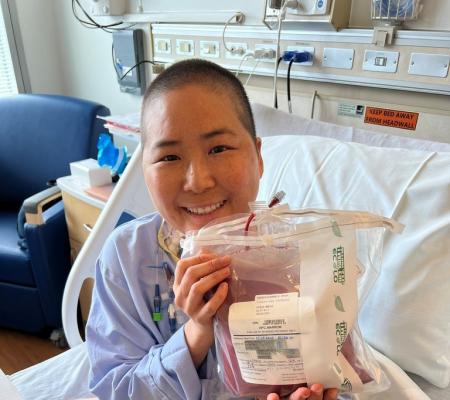

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309