-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

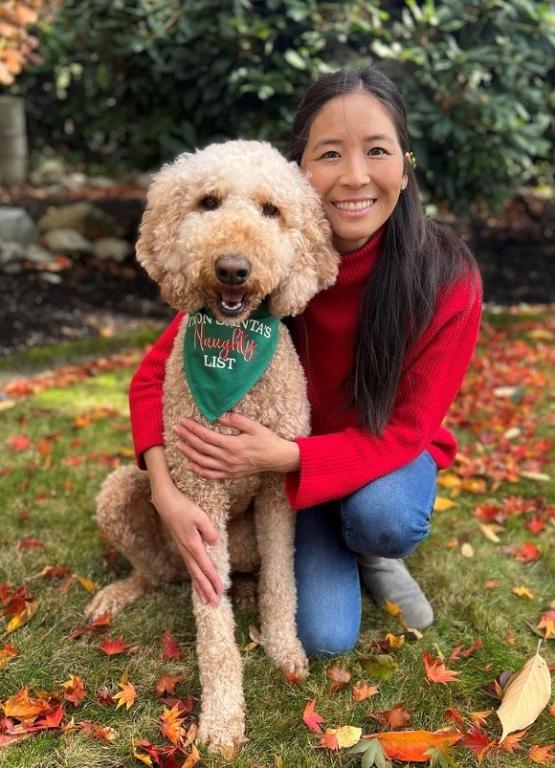

As a 35-year-old, Irene Chen spent a month in a hospital battling symptoms caused by norovirus. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea forced Chen to the bathroom several times a day, with sleep her only relief. After losing 30% of her body weight, Chen weighed only 80 pounds. Her family discussed end-of-life plans with the doctor.

“There was a possibility that I might not recover from this,” said Chen.

With the help of antibiotics, oral immunoglobulin, and other supportive care measures, Chen improved. That’s when her immunologist urged her again to consider a bone marrow transplant (BMT), also known as a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), to treat her common variable immune deficiency (CVID). . CVID caused by with NFKB1 haploinsufficiency had caused recurrent and severe respiratory and sinus infections, severe skin rashes, and an autoimmune blood disorder throughout Chen’s life.

Even though she used intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) to treat her condition starting when she was a teenager, Chen experienced an immune system decline as she got older. At the time of the norovirus infection in 2022, her T and B cells barely functioned.

“It was a traumatic year,” said Chen.

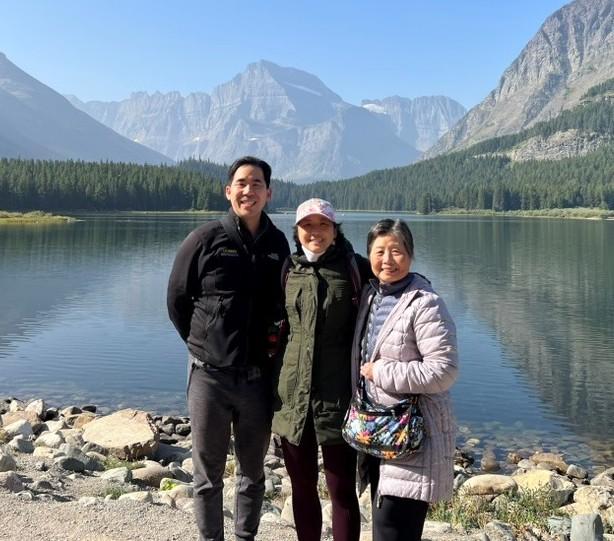

Chen agreed to undergo BMT and today has a functioning immune system. The treatment journey proved difficult, and Chen still has other health issues. She is grateful for the expertise at the Seattle Children’s Hospital’s primary immunodeficiency (PI) research center that referred her to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), where she got the BMT.

“Now that I've experienced being a patient at an academic medical center and at the NIH, where all they do is the rare disease, if I could go back, I would have gone to an academic center for my medical care when I was younger, but we were using the information we had at the time. We had an HMO, so we could only stay in-network with providers,” said Chen.

As a child growing up in California, Chen had bronchitis three to four times a year. Each time, the illness progressed to chronic sinus infections, and pneumonia requiring hospitalization.

“My mom would always ask the pediatrician, ‘Is there something wrong? My daughter seems to always get ill.’ But the pediatrician kept saying, ‘Oh, she's fine. She's in school. Kids pass around germs all the time. This is normal.’ But the thing that really wasn't adding up was that I was constantly having to use antibiotics to get over these infections,” said Chen.

In eighth grade, she developed hives and angioedema, a condition that caused her face and lips to swell. The symptoms appeared at night, and every morning, she woke up exhausted from scratching and groggy from the antihistamine prescribed by the allergist.

About the same time, she got another cold that progressed to pneumonia. Her regular pediatrician wasn’t available, so she saw a doctor who had just completed his fellowship at the University of California, Los Angeles. Concerned about Chen’s repeated infections and almost monthly use of antibiotics, he ordered blood work. A week later, he referred Chen to an immunologist because of her low immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin A (IgA).

Once she received the CVID diagnosis and started treatment with IVIG, she had fewer infections and hospitalizations, but the hives persisted. She missed about two months of school each year, but strong academic skills allowed her to make up work and get good grades.

Chen often needed to take short courses of steroids to control the hives. Her family changed shampoos, detergents, and lotions, ripped up carpets and installed hardwood floors, changed to hypoallergenic bedding, and gave away the family dog. Nothing worked.

College brought good and not-so-good health news. Chin’s hives disappeared in college, for no apparent reason. Then, after emergency surgery to remove her appendix, she learned she had an autoimmune blood disorder called Evans syndrome. In Evans syndrome, a person’s immune system attacks healthy blood cells, usually red blood cells and platelets. Sometimes white blood cells called neutrophils are also affected. Because of Evans syndrome, Chen’s platelets, hemoglobin, or white blood cell counts periodically dropped to critically low numbers, requiring hospitalization.

Health issues didn’t stop Chen from moving to New York City after college to pursue a career. A self-described Type-A personality, Chin enjoyed running at least 5 miles a day through the city. When she got a painful blister on the ball of her foot that wouldn’t go away, she went to the emergency room three times before they agreed to drain it. The treatment, Bactrim, sent Chen into anaphylactic shock, a severe allergic reaction. She was rushed to the hospital and intubated.

“The intubation was very traumatic, but that was probably what actually saved my life because once I was intubated, the doctors took me seriously,” said Chen.

Even though she still felt pain in her foot, imaging didn’t show infection. Family members, who were doctors, advocated for surgery, and sure enough, surgeons found pus and infection.

At this point, Chen needed support from family members to navigate her health challenges, so she moved back to the West Coast. She earned a pharmacy degree from the University of Southern California in 2018 and, after graduating, worked in the pharmaceutical industry in cancer research and development.

The job provided Chen access to an immunologist who specialized in PI at the Seattle Children’s Hospital. The immunologist urged Chen to undergo BMT each time she visited for a check-up, starting in 2019. The mortality rate is high for CVID patients who receive BMT, but for those who survive, the treatment is beneficial. Chen didn’t follow through with the immunologist’s recommendation at first.

“If you ask me if I thought anything of it at the time, I'm pretty sure I didn't really even hear her. You internalize it. I thought that I’d get a BMT at some point in my life, but I didn’t think it would happen so soon,” said Chen.

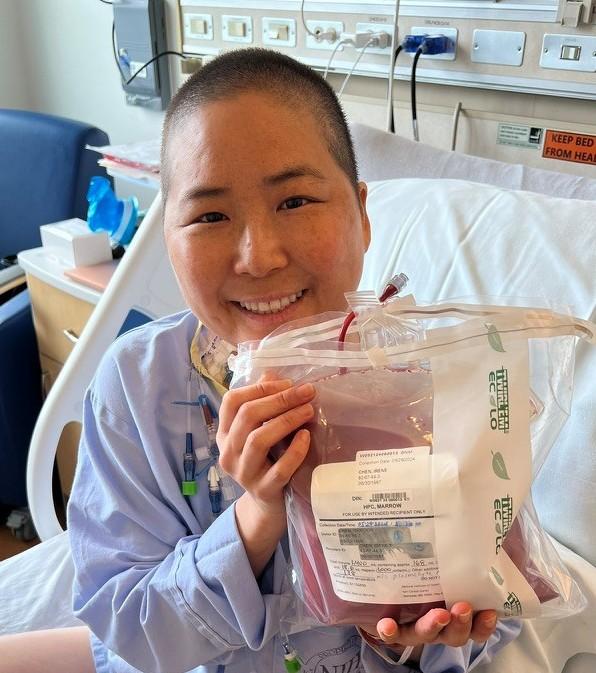

The norovirus diagnosis in 2022, coupled with the steady downward trend of her T and B cell function, eventually spurred Chen to choose BMT. She spent a year building up her strength and then traveled to the NIH in spring 2024. Doctors transplanted Chen on May 29 with stem cells from her brother, who was an exact human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match. The BMT was successful, with the donated stem cells producing new, working immune system cells. At the end of August, the NIH released Chen to go home to Seattle.

“There's nothing you could have said to me to prepare me for the transplant, even as someone who works in oncology and talks about transplant data to doctors,” said Chen.

“When you're the one in it, none of these hazard ratios or overall survival or progression-free survival numbers matter. I don't care how many percent of people got diarrhea or got a rash, when it's happening to you, you're the N of one, right? Everything about the transplant was worse than I expected.”

Chen continues to recover from the transplant. She’s had a few infections, significant fatigue, and eating challenges due to the post-BMT medicine. She is on thyroid replacement therapy and could have permanent adrenal insufficiency, which means her body doesn’t produce enough hormones.

Family and friends support her, but sometimes they can’t grasp that she is on a journey that doesn’t end just because she’s received treatment.

“Some of my friends will say, ‘Oh, you’re done, right?’ And I tell them, ‘Well, it’s a little more complicated than that.’ I think it’s hard for people to understand if they’ve been healthy their whole lives,” said Chen.

“Even now that I have been transplanted and I will eventually have a normal immune system, it doesn’t negate the fact that I have to be on higher surveillance because I’ve had chemotherapy. I’m also menopausal now at 38. There are a lot of lifelong implications, even though my immune system is cured.”

Chen’s medical journey inspired her to work in the health field, and she hopes to return to her career as a pharmacist. Medical careers run in the family—her mother is a nurse and her brother is a doctor.

“I think when you're in a family that deals with something so intimate, how can it not impact your life decisions? So, my diagnosis definitely pushed me to want to be in healthcare,” said Chen.

Alongside her job search, Chen keeps a blog of her medical experiences and volunteers for the Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF). As a plasma ambassador, she visited a plasma donation center and thanked donors for their contributions. She is also a peer mentor, talking to other newly diagnosed patients about their journeys, and she volunteered for the Walk for PI in Seattle. Staying involved helps her connect with others and boosts her drive to move forward.

“I volunteer to help others with PI because I want people to know that they aren’t alone. It can feel isolating when you are a zebra, so I hope that I can help others weather hard times, as I can empathize with their lived experience,” said Chen.

2026 PI Conference

Join us June 25-27, 2026, in San Antonio, Texas, for a transformative experience where stories connect, voices unite, and journeys inspire. No matter where you are in your primary immunodeficiency journey, access expert-led education, meaningful connections, and cutting-edge insights from world-renowned immunologists.

Register nowRelated resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Why PI affects the skin: Common rashes, infections, and immune dysregulation (dermatology deep dive)

Decoding PI: Dermatological issues in PI

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309