-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

When researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) asked Bryce Powerman to participate in a clinical trial to treat his DOCK8 deficiency, a rare primary immunodeficiency and type of hyper IgE syndrome, with a bone marrow transplant (BMT), the 17-year-old declined. At that point, the study yielded a survival rate of just 50%, partially because some patients had irreversible pre-existing health problems.

Two years later, Powerman changed his mind. Study results had improved, and no other treatment existed to extend the life of a person with DOCK8 deficiency past age 30.

“I remember being at NIH, and my doctor said, ‘This is a really good time to do this, and if we wait, one of your skin issues or one of your infections is going to turn into cancer. That’s where we’re seeing the outcomes for all DOCK8 patients’,” said Powerman.

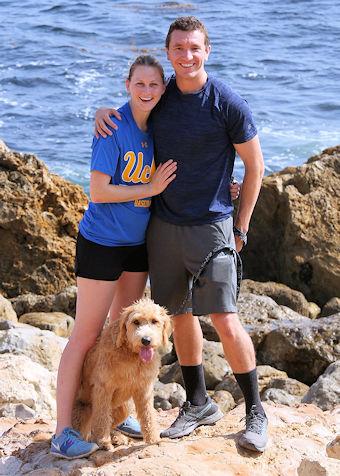

The 19-year-old University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) sophomore withdrew from college, entered the study, and underwent BMT. Nine years later, Powerman is healthy and requires no medication or treatment to support his immune system.

“It honestly was fully curative. It’s an uncommon thing to say, especially in rare diseases. It was amazing,” said Powerman, who described watching his skin heal as he engrafted just after the transplant. “I don’t take a single pill, which is incredible considering I took a dozen a day… I just had my 9-year visit to the NIH, and all my counts look good. I’m incredibly lucky.”

DOCK8 deficiency is named after the affected gene, dedicator of cytokinesis 8, and is associated with high levels of immunoglobulin E. It is one of several causes of hyper IgE syndrome. Persons with DOCK8 deficiency have lower numbers of immune cells, which are unable to penetrate thick tissue to protect the skin and lungs. Patients experience recurrent bacterial and viral infections of the skin and respiratory system, may have food allergies and asthma, and are at high risk for lymphoma (a type of blood cancer) and skin cancer. DOCK8 is fatal unless treated with BMT.

Throughout childhood, Powerman coped with symptoms including severe eczema; ear, sinus, and bronchial infections; and extreme warts. Eventually, blood tests revealed that Powerman had only one-seventh of the normal levels of white blood cells. Multiple specialists treated the medical problems but could never provide a diagnosis. Powerman recalls how doctors tried in vain to remove his warts with lasers, injections, creams, and freezing techniques. His parents even tried alternative options like oatmeal baths.

At age 7, Powerman started limping. Doctors suspected a rare bone cancer and told his parents they may need to amputate his leg. Instead, doctors found a bone infection during surgery and were able to remove the infection without serious issue.

During the recovery period, a clinician noticed the unusual combination of symptoms and recommended the family contact the NIH about a program for patients with undiagnosed immunodeficiencies.

“My parents dogged the head doctor at NIH, emailed him pretty relentlessly,” said Powerman.

In 2001, NIH admitted him into the program for patients with hyper IgE syndrome, and eight years later, after researchers discovered DOCK8 deficiency, he joined the DOCK8 cohort.

“It was really kind of a miracle,” said Powerman of his acceptance into the NIH program, both in terms of the care and the fact that the study covered all expenses.

Into his adolescent and teen years, growing up in Boulder, Colo., Powerman pursued activities he enjoyed despite hurdles posed by his condition. When the skin on his fingers cracked from playing piano, he taped them up. When his fingertips bled and cracked from playing basketball, he superglued the skin together. When he felt bad from a lung infection at school, he kept going until teachers ordered him to go home.

“I didn’t want to be held back by it,” said Powerman.

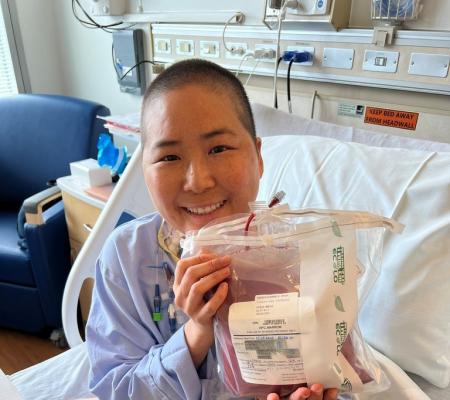

The BMT proved lifesaving for Powerman, but the treatment did pose short-term health challenges. During the hospital stay post-transplant, he developed acute graft versus host disease (GVHD), contracted Clostridioides difficile (C. Diff) twice and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The infections forced him to enter medical isolation, and the combination of GVHD and infections caused him to drop from 180 to 140 pounds.

Despite those setbacks, Powerman engrafted on schedule and made it clear to doctors that he wanted to leave the hospital and return home as soon as possible.

“I’m a very social person, and so a lot of my drive was to get back and have the college experience, get back with my friends, and return to normalcy,” said Powerman, who turned 20 years old in May 2014 while hospitalized at NIH. “I had also met my now-wife about two months before leaving for D.C., and we were communicating every day.”

Following his BMT, Powerman returned to UCLA and graduated with an economics degree, but his interest in the healthcare field has guided his career. He established a non-profit dedicated to providing support for those diagnosed with DOCK8, the DOCK8 Foundation, and he’s currently employed in strategy and partnerships at a genetic testing company. He said he believes that DOCK8 is underdiagnosed.

“Early diagnosis with genetic testing is critical,” said Powerman.

Powerman said as a younger man, he shied away from connecting with others through patient advocacy groups, but now he better understands their importance.

“Lean on the community. I’ve not been great about being involved with the support groups that exist out there, and I think that can be really helpful,” said Powerman.

“It’s intimidating at times. It’s just so personal, but people have had that experience, and it’s just an amazing resource.”

IDF offers support for those with PI and their families through our Get Connected Groups program. Find the one for you on our events calendar.

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.