-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

The average time to diagnosis for primary immunodeficiency (PI) is nine to 15 years, and while it took Gary Newton only two years to discover that PI caused his chronic severe lung illness, it was a time fraught with hospitalizations, surgery, strong medications, and a trip halfway across the country to determine the reason for his poor health.

Newton’s symptoms started just as he left on a week-long trip abroad as a senior advisor for public investment with Save the Children, an international nonprofit. Having worked for decades in international development, Newton had traveled sick before. So, when the fevers, sweats, chills, dry cough, and shortness of breath continued through his scheduled workshop in Jordan, he took prescribed antibiotics and kept going.

The day after he returned home to Washington, D.C., Newton had a 104-degree fever and struggled to catch his breath. Doctors admitted Newton to the hospital for acute respiratory distress, and X-rays and CT scans showed inflammation, fluid, infection, and nodules in his lungs. The 63-year-old had just finished a half-marathon in April but now got winded just brushing his teeth.

Doctors tested him for two dozen conditions and diseases and administered a staggering number of antibiotics and antifungals. By day 12 in the hospital, doctors deemed him well enough to go home.

“On the day of discharge, my pulmonologist said, ‘It’s possible, nothing we did in the hospital made any difference whatsoever other than providing oxygen,’” wrote Newton in a memoir he penned about his experiences with PI.

Though Newton kept up with the treatment of antibiotics and oxygen at home, the disease progressed. He went back to the hospital in late June.

“Considerations from the radiologist’s report included cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), lymphoma, bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma, and sarcoidosis. ‘Considerations’ is a term of art used when radiologists throw spaghetti on the wall to see what sticks, the strands of pasta being possible causes of my messed-up lungs,” wrote Newton.

Worried about further deterioration of Newton’s health, doctors performed a lung biopsy and diagnosed him with COP, a rare interstitial lung disease characterized by inflammatory tissue filling the small airways in the lungs, making it difficult to breathe and causing flu-like symptoms. The cause of COP is unknown.

“The pathologist told my doc that he’d never seen so much pathology before… With this much damage to lung infrastructure, especially alveolar walls, I was told we could expect some fibrosis—permanent scarring—which he hoped would be minimal and wouldn’t affect normal lung functioning. He said the treatment would likely take some time,” wrote Newton.

High doses of steroids eased Newton’s symptoms, but relapses occurred, and his lungs struggled to improve. The first relapse happened in August 2013, after a trip to Massachusetts to attend his mother’s 90th birthday celebration.

“Back at home in D.C., dealing with breathlessness and fatigue, a slight fever, rales (rattling in the lungs) on the left side, night sweats, and minor aches and pains, I’m thinking to myself, good Lord, dear old Ma, born when Coolidge was president, is in better shape than I am. There she is playing tennis, bridge, scrabble, eating jelly sticks at Dunkin’s, baking cupcakes with the grandchildren, and here I am getting winded washing my thinning hair,” wrote Newton.

After several more relapses, doctors finally sent Newton to National Jewish Health (NJH) in Denver in September 2014, where he was under the care of the director of the NJH Interstitial Lung Disease program. Tests ruled out autoimmune disease and a rare type of pneumonia, but they did find what the doctor called “common variable immune deficiency (CVID) in evolution” because of his low immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels.

In late 2014, Newton sought care at Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, and by June 2015, doctors confirmed the diagnosis of CVID based on his low IgG levels, low IgM levels, poor antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines, and history of organizing pneumonia. He started subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) replacement therapy in July 2015.

“In an ideal medical scenario—and mine was as close to ideal as they get—had my low IgG level raised a red flag in June 2013, immunoglobulin therapy could have started much earlier. This is in no way a complaint. I was lucky to get a diagnosis and treatment as fast as I did,” wrote Newton.

Newton moved to New York City in 2019, and a new immunologist adjusted his diagnosis. Based on his weak responses to vaccines, history of lung infections, and low IgG, the doctor concluded he didn’t have “clear-cut CVID” and changed his diagnosis from CVID to nonfamilial hypogammaglobulinemia/selective deficiency of IgG subclasses.

Newton continues to use SCIG to stay healthy and said he is overwhelmed by the generosity of plasma donors, the source of his treatment.

“My antibodies could be from anybody, so I feel a kind of kinship with everybody. Random folks I stand next to in a queue may well be the source of my antibodies,” wrote Newton.

Newton continued traveling for his job in international development several years after diagnosis but resigned in 2019 because of infection risk. Still, he is healthy enough to exercise and even ran two half-marathons. He enjoys spending time with his family in Maine, where he currently resides.

While he may never know the exact reason for his lung condition and diagnosis, Newton learned to appreciate that sometimes science doesn’t have all the answers. He recalls a conversation with a doctor that illustrates how much more progress needs to be made in understanding the immune system.

“After an appointment with my immunologist at Mount Sinai, we walked together to the elevator, and she talked about unresolved aspects of my case. At the elevator door, before she went up and I went down, I said, ‘Guess we still have things to sort out.” As the elevator door closed on me, she said, ‘Maybe you’ll never get sorted out,’” wrote Newton.

“Having a rare manifestation of a rare disease involved accepting the fact that relatively little is known about my two conditions and how little is known generally about the goings-on at the intersection of our divinely complex and wondrous respiratory and immune systems.”

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

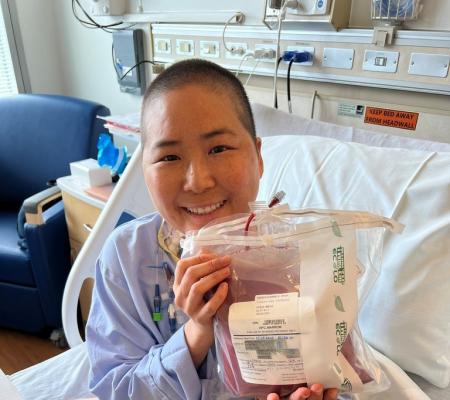

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309