-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

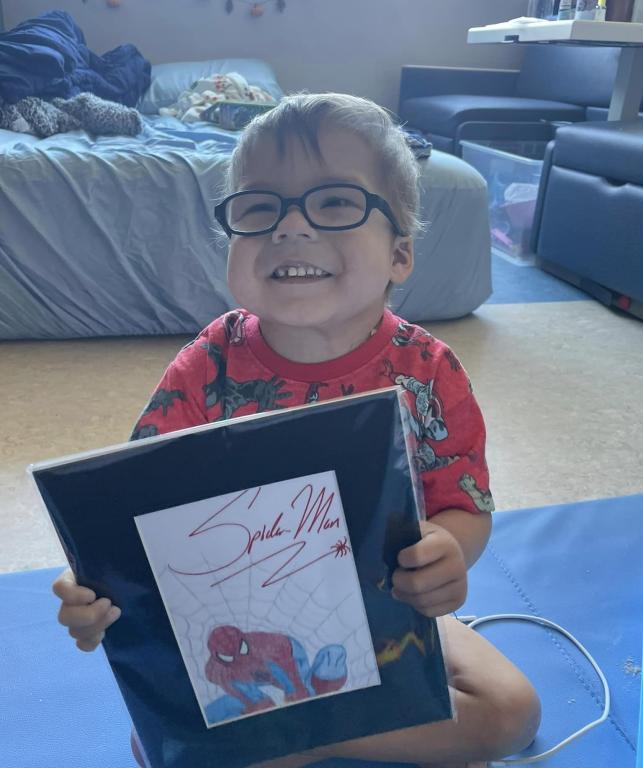

Chelsy Nolasco has stood at the doorway of her son’s hospital room and blocked healthcare workers—including surgeons—from coming in if they weren’t wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). PPE is essential for interacting with Gabriel Nolasco, who doesn’t have a thymus, the organ necessary to produce working T cells for the immune system.

“You are not walking in here without a mask, gown, and gloves. I have never cared who you were or where you went to school. That doesn’t matter. My job is keeping my son safe. And I plan on doing that fiercely and effectively. And that’s how I have a 4-year-old who has lived four years with no immune system,” said Nolasco. “I do not think my son would be alive if his parents did not advocate for him the way that we have.”

Fierce parental advocacy is characteristic of Chelsy and Eric Nolasco’s approach to their son’s care. Gabriel has complete DiGeorge syndrome, also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, in which a tiny piece of chromosome 22 is missing. DiGeorge can affect multiple organ systems and, in Gabriel's case, resulted in a non-functioning immune system due to a missing thymus, a condition known as congenital athymia; heart defects, and a cleft palate.

In October 2023, Gabriel received a thymus tissue implant to provide him with a working immune system. In a thymus tissue implant, specialists take donated thymus tissue and surgically implant it in the child's thigh muscle, where blood vessels are plentiful. Hematopoietic stem cells circulate through the thymus tissue and learn how to become healthy T cells, creating a functioning immune system. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the regenerative treatment, called Rethymic, in 2021 after 30 years of development by researchers at Duke University, where Gabriel underwent the procedure.

Doctors released Gabriel from Duke University Hospital in November 2023, and his family—parents Chelsy and Eric, and siblings Elliana, 6, Isaiah, 8, and Jonathan, 13, all live with him in isolation at a Ronald McDonald House in Fort Worth, Texas near a children’s hospital as he recovers.

“It’s a long process. You fight to hurry up and wait,” said Nolasco.

A heart repair

Fighting for Gabriel is something the Nolascos have done since his birth in July 2019 when a congenital heart defect threatened his life and doctors put him into a medically induced coma. His parents had to choose whether to move forward with surgery that offered low chances of survival or not to treat their son.

“In the beginning, the doctor presented a very grim prognosis. He said, ‘I don't think I can save your son. I don't think he's going to make it off my table. He's too weak. He's too small. You know, kids like this, they don't survive. If he were my kid, I would take him into that palliative care room, and I would hold him, and I would give him a controlled death where he dies in his mommy's arms. Because the alternative is he's going to die on a cold surgery table without his mama.’ And he said it very plainly. And that was what we needed at that point in the odyssey,” said Nolasco.

“My husband and I looked at each other, and there was no question. We were going to give our son a chance because God told us to. We felt if there was even a one percent chance of hope, we were going to take it. I'm so grateful that we did.”

Gabriel underwent heart surgery at two days old and received his final heart repair at two months old. Because he only weighed 10 pounds, the swelling prevented doctors from closing the incision, and sepsis set in.

“He beat it. He survived. He was in a medicated coma for two weeks, but he survived. He was alive. He cleared it. And that was phenomenal,” said his mother.

A diagnosis

Chelsy and Eric Nolasco learned their son had DiGeorge syndrome and congenital athymia within the first weeks of Gabriel’s life. Even though thymus tissue implants were still in clinical trials at that point, the doctors directed the family to Duke University Hospital to join the thymus tissue implant waiting list. Doctors told them that Gabriel would go straight from the Texas hospital where he’d been treated to Duke when the time came for the implant. But the pandemic—and pushback from Medicaid on coverage of the procedure—delayed Gabriel’s opportunity to move up on the list.

“A big part of the delay was the pandemic. The FDA stalled everything for about 18 months. We were 20-something on the waiting list. That’s how behind we were, so I didn't feel the need to fight for him to get it done because there was a list, and we just had to wait our turn,” said Nolasco.

“But then, as you get into the community, you start seeing that these kids are dying while they're waiting. You're seeing that there's this gap in healthcare of Medicaid not wanting to work with them. And so it took a couple of years to start getting into that side of it. But then, once you start seeing it, I just got so enraged.”

The family looked into having the thymus tissue implant performed in the United Kingdom, but with a price tag of $600,000, they couldn’t afford it. The only way they could get the lifesaving procedure done for Gabriel is if Medicaid covered the $2.7 million cost, said his mother.

An infection

As they wrangled with Medicaid, Gabriel recovered from the heart surgery and returned home. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy and preventative antimicrobial medications kept infection at bay until August 2022, when he caught norovirus, an intestinal virus that causes vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain. Healthy people clear the virus within a few days but Gabriel, with no immune system, struggled.

Within a month, Gabriel had lost 10% of his body weight and weighed 19 pounds. Though his symptoms improved with treatment, his low energy level and weight loss prompted his parents to have his heart checked. They set up an appointment for a heart catheterization, a procedure where a tube is guided through the heart to provide details about its function.

Chelsy Nolasco typically waited alone during these types of exams, while husband Eric stayed home to take care of the other three children, but this time, her intuition and an impending sense of doom told her to have support, and her uncle came along. Gabriel’s catheterization took longer than it should have, and Nolasco braced herself.

“I knew something was wrong. The nurse came and put me in a consultation room, and my heart sank. My trusty doctor walked through the door, and you could see it all over her face—something had happened. She sat down and told me that she had to perform compressions (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) on my baby. She said she went into one of his pulmonary veins to try and stent it, and he began to code. She said he was much weaker than she anticipated,” said Nolasco.

“We knew at this point he was so sick because of his noro. It was weakening him. We scheduled heart surgery for November and were discharged a few days later. My once energetic sweet boy was a shell of who he used to be.”

As they waited for heart surgery, Gabriel’s health declined further, and the Nolascos called Duke University Hospital directly for advice. Their response saved his life.

“The doctor there said, ‘They need to get this child on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and lipids, or he's going to wither away and die in front of you.’ So, I turned around, and within 24 hours, he was on TPN and lipids because I told them this was what Duke said,” said Nolasco.

TPN and lipids, a calorie-rich component of TPN, provided Gabriel with a liquid form of nutrition through a tube directly into his port. The nutrition strengthened Gabriel, and he made it successfully through his third heart repair surgery in October 2022.

More setbacks

Just as the Nolascos prepared for Christmas 2022, Gabriel faced more medical challenges.

One day, when the family was taking a walk together, he doubled over, screaming with stomach pain, and spiked a fever near 103°F. His parents loaded him in the car and sped down the highway to the hospital. Doctors diagnosed Gabriel with intussusception, a condition where the tube-shaped intestine collapses back into itself like a telescope, causing bowel blockage.

Though doctors treated the condition, it spawned another problem. When the intestines collapsed, they released bacteria into his system and caused infection in his heart, leading to endocarditis, which is inflammation inside of the heart chambers and valves. Antibiotics cleared most of the infection, but some endocarditis remained.

In February 2023, Gabriel developed rogue T cells that caused autologous graft versus host disease (GVHD). The rogue T cells developed because Gabriel had no thymus to weed them out. Instead of protecting Gabriel’s body, they attacked him, causing GVHD. Doctors monitored him closely to make sure the T cells weren’t inflicting damage on his liver, which showed signs of distress.

Meanwhile, Chelsy and Eric Nolasco advocated for Medicaid to cover Gabriel’s thymus tissue implant. They launched social media campaigns, made T-shirts, and contacted the state health and human services department and elected officials. State officials promised results but never followed through.

Gabriel’s situation grew even more dire in July 2023 when the rogue T cells ramped up the GVHD symptoms.

“The GVHD started in the skin, and it looked like we had just dropped him in boiling water, and it was just horrific,” said Nolasco. “We were supposed to be in transplant. We were supposed to already be admitted at Duke at this point.”

State officials broke their promise twice to have Medicaid cover the thymus tissue treatment. The second time, the Nolascos were on their way, driving to the Texas hospital to have a port put in Gabriel's chest in preparation for the transplant.

“We were supposed to be on a plane to go to Duke in five days. I'm frustrated. We've waited so long. We're having to go through this again. He's got graft versus host again, but his heart is good, we're OK, and we’re ready,” said Nolasco.

“At this point, I screamed to anyone that would listen. ‘Y'all are going to kill my kid. He needs to get to Duke. I don't care about the insurance. I don't care about this red tape.’ It was an intense anger.”

A victory

After emailing their senator’s office several times and getting no result, Chelsy Nolasco picked up the phone and called. A representative of the senator picked up the line.

“I bared my soul out to a stranger, and she said, ‘We're going to make this right.’ Within two hours of that phone call with the senator's office manager, I was in a meeting with the head of Medicaid and the head of different departments in health and human services because they had kept telling me it was expedited. Six weeks, I was told it was expedited. And at that point in the call, I was done,” said Nolasco.

“I didn't think I was going to have the floor, but they gave me the floor, and I gave them the story in about 10 minutes. I summed it up and told them, this is what I need. And within seven days, we were on a plane going to Duke. It's what you have to do as a parent.”

Gabriel is the first child under Texas Medicaid coverage to receive a thymus tissue implant since the FDA approved the treatment, said his parents, and his case has paved the way for other Texas children with congenital athymia on Medicaid to undergo the treatment.

“Eric and I are so proud of that,” said Nolasco.

The implant and recovery

The Nolascos arrived at Duke in late September 2023, and after doctors provided treatment to get Gabriel’s GVHD under control, his thymus tissue implant took place on October 24, 2023. Chelsy Nolasco said she felt honored to meet the doctors who administered the treatment, and she soaked in as much knowledge as possible.

“It was great to meet the people who made it possible to save my kid's life and showed me that there was something to fight for. There was not a cure necessarily, but there was hope. And to fight for that hope, they gave that to me,” said Nolasco.

Mother and son returned home in November to reunite with Eric and the children, and December 2023 was the first full month Gabriel hadn’t been in-patient in a hospital since July 2022. He is recovering well, weighs 30 pounds, and is regaining energy. The family and doctors hope to see working T cells within the next year and for the norovirus to clear as Gabriel’s immune system grows.

Being in isolation for the past few years, the Nolasco family has missed a lot—visiting with family, supporting ill family members, attending school in person, and going to public places.

“We have had to watch the world go by in this locked-up prison bubble of isolation. But because we did that, we have a little boy who gets to run on video and say, ‘Hi.’ We have a kid that is alive and well. And that sacrifice we’ve made, we’d do it a hundred times over,” said Nolasco.

Nolasco said faith in God and Gabriel himself have kept the family going through such stressful times.

“We have felt God in a way that is unbelievable and that we had never experienced, and you never probably will unless you've been in shoes like ours. You feel God in the hospital more than you ever did in church. So we will say, first and foremost, that has kept us together and moving forward,” said Nolasco.

“Secondly, just seeing Gabe. Just seeing him thrive and survive and beat the odds. He has beaten all the odds and anything that's ever been put up against him. He is this resilient, strong, phenomenal kid, and it is an honor to be his mom and see him survive—that’s it. That's what we wanted. That's what we fight for in our community.”

The congenital athymia community is a vital support system that allows parents to be seen and heard and reminded that the life of their child matters, said Nolasco. Her goal is to one day build a career in advocacy, helping others navigate the rough waters of rare diseases.

“We have newer families that reach out to us and ask us questions. And I love that. I love being the one to say, this is what it can look like. I love helping and explaining these are the guidelines that we followed. This is what we've done. Try this doctor. It's cool to be on that side of it now instead of the one that's looking for guidance,” said Nolasco.

“Sometimes I feel very insufficient. Like, how could I possibly be that? You know, and I am still in my 20s, but I feel like I've lived enough for about a 90-year-old at this point.”

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

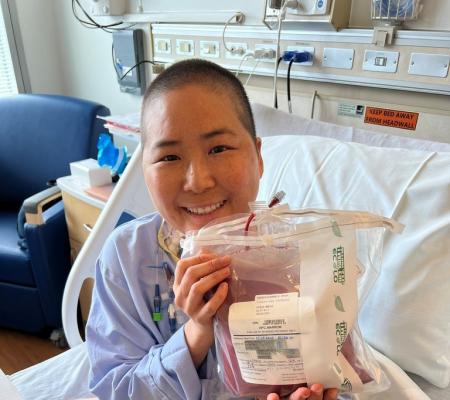

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.