-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Denise Reich recalls the time a clinician looked at her chart and questioned her about the number of specialists she saw. Her records included a cardiologist, immunologist, hematologist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, and neurologist. The needle marks on her arm made him even more suspect. An orthopedist-in-training, the clinician wrote a derogatory note in her file. Reich spoke with the attending physician to get the comments removed.

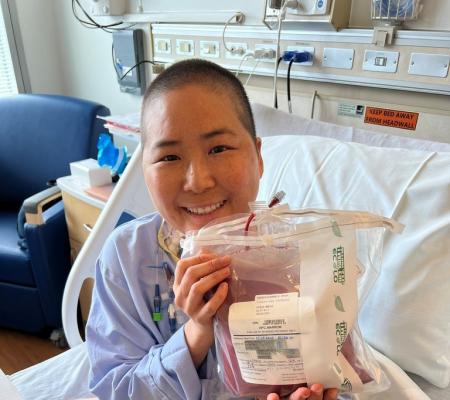

Reich is diagnosed with common variable immune deficiency (CVID) and takes intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy to prevent infection. She lives with other chronic illnesses that include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, high heart rate (tachycardia), and extreme daytime sleepiness (hypersomnia). The negative interaction with the orthopedist isn’t unique in her experience.

“I think that there is a bit of hostility with chronic illness patients that come in, especially when we've got a couple of diagnoses, that I find very hard to get around. The fact is, even if doctors don't know what you have, they don't want to know. They don't listen to you,” said Reich. “There needs to be an awareness among doctors that if you have CVID or another type of immune deficiency, you're going to see multiple specialists.”

A writer, Reich often details challenges navigating healthcare during her medical journey. In one story, she shares how an incorrect diagnosis appeared in her records and the effort it took to remove it. In another, she talks about how patients are encouraged to educate themselves on their diagnosis but are viewed with suspicion if they know too much.

“I feel like there's a big lack of understanding of how a complex patient who sees different specialists will probably be knowledgeable about the condition they have. Just by sitting in the room and watching them do IVIG, you absorb things. You learn the language, you get an understanding of how things go,” said Reich, who now presents clinicians with letters and bloodwork from her immunologist and cardiologist.

“I offer them that information because I want to make it clear, no, I didn’t just diagnose myself off the internet. There are diagnostics for it, and you can talk to the doctors who treat me, and they can verify anything that I’m telling you.”

The struggle to find competent medical care is a topic with which Reich is all too familiar.

Reich spent much of her early childhood ill. She was diagnosed with her first infection at 6 weeks old and continued with frequent ear, gastrointestinal, and skin infections through age 5. She had Rocky Mountain spotted fever at 6 and scarlet fever at 7. Doctors provided antibiotics but didn’t suggest further testing.

Although elementary school brought a reprieve, symptoms returned in middle school, and by high school she struggled to get through her days. She slept on the floor in the high school library during lunches and sometimes skipped classes to go home because of extreme fatigue. Monthly infections returned and she developed asthma.

“I was run down and tired, but unfortunately I was looked at as being lazy or just having senioritis,” said Reich.

Reich’s health didn’t improve in college. Ear tubes inserted to control infection caused sores and bleeding. She had her tonsils out, but the procedure failed to prevent infections.

While juggling her health issues and attending college, Reich also worked full-time as an usher on Broadway. She enjoyed the job, but the rigorous schedule of going to class and then working wore her down even further. She took antibiotics almost every day.

“I was so exhausted I could barely see straight,” said Reich.

She earned a degree in theater and attended a French language program at a university in central France—but also got pneumonia that required two emergency room visits and several rounds of antibiotics to clear. After trying to attend another program at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, her poor health forced her to return home.

“It was to the point where my body was like you can’t do this anymore,” said Reich.

Reich continued her job as an usher for 10 more years and earned additional income through freelance writing, publishing articles in “Chicken Soup for the Soul” books, news outlets, Mary Beth’s Beanie magazine, and Shameless magazine. She sought treatment for her infections at the local community health clinic.

“Our culture is very much ‘just keep going.’ I was doing what I thought I was supposed to be doing, which was no matter how much this hurts, no matter how tired I am, no matter how much I’m disabled and shouldn’t be doing this, I’m going to be doing it anyway because that is what I’m supposed to do,” said Reich.

In the early 2000s, she moved to California seeking a more laid-back pace of life. Because she had trained as a dancer since she was a toddler, Reich decided to put her dancing skills to work. She performed in flash mobs, dancing in five episodes of Howie Mandel’s “Mobbed,” a reality television show, and was a dancer at the Special Olympics and other sporting events. The dance gigs didn’t pay and while Reich had fun participating in them, she also paid the price.

“These were all hobbies that took a few hours and that was it, and what nobody saw was that after dancing for four minutes, I was limping backstage, coughing, short of breath, in a fair amount of pain, and sleeping for several days when I got home,” said Reich.

An infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in 2014 forced her to take a leave of absence from her job as a docent at The Museum of Tolerance, a Holocaust education center. Six months after treatment, she sat in her doctor’s office still exhausted and ill.

“I think I reached that point—and I’ve heard other CVID patients talk about this—where my body finally had enough and said, ‘You've pushed me past the point where I can cope with this. We are absolutely done. No more.’ And I never got better from that,” said Reich.

Unable to work due to her health, Reich pursued a diagnosis for her lifelong struggle with infections and fatigue. Her primary care provider referred her to specialists and Reich learned some of the reasons for her poor health, including inappropriate sinus tachycardia, a condition that causes rapid heartbeat, and hypersomnia, which causes excessive sleepiness.

After two years of seeing specialists who downplayed her concern about repeated infections, a rheumatologist agreed to test her immunoglobulins. The results showed abnormal levels of IgA and IgG subclasses. Her doctor encouraged her to see an immunologist.

“I am so grateful to my primary doctor for pushing me to just keep going because at that point I was sick of hearing, ‘Keep going. Don't let it stop you. You can do it. You can overcome it.’ I'd given up. I was just like, no, I can't anymore. I actually can't. The fact that she very gently said, ‘OK, let's talk this through’ and got me to see a doctor who knew what he was talking about made all the difference,” said Reich.

“My primary care doctor is the absolute best, and I told her straight out, ‘You saved my life.’ I made it clear I appreciate her.”

An immunologist and PI specialist diagnosed Reich initially with partial IgA deficiency and then specific antibody deficiency (SAD) after further testing. The diagnosis progressed to CVID in 2020. She started treatment with IVIG in 2018, which reduced her infections.

Reich said her PI diagnosis explained a lifetime of struggling with sickness and proved she was right about her hunch that something more was wrong. While she has had to accept that there is no cure, only treatment, she appreciates the knowledge.

“I was relieved, and I was vindicated because it proved I wasn’t being dramatic. I wasn’t overreacting. I wasn’t anxious. There was something that needed to be addressed. It’s knowing what the monster under your bed looks like and saying, ‘OK, now I see you,’ and there was relief in not having a great unknown anymore. Now it had a name and a definition,” said Reich.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309