-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

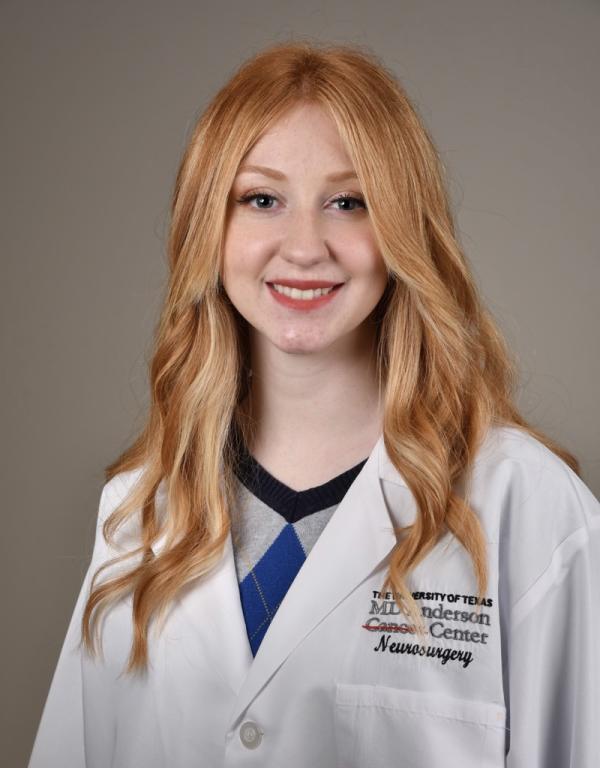

Mekenzie Peshoff studies how the brain’s innate immune cells target cancer cells. The brain’s innate immune system cells, a type of macrophage called microglia, either destroy cancer cells in the brain or are taken over by the cancer cells and add to brain tumor growth. Peshoff’s research focuses on activating a pathway in the microglia that boosts their ability to overcome the cancer cells and eliminate them.

For Peshoff, diagnosed with selective IgA deficiency, the work is transformative.

“I was always intrigued by the brain, but when I learned about the field of neuroimmunology, it made something I was interested in feel more personal. I’d had such a negative relationship with the immune system because I thought of it as being the cause of my issues. But when I was introduced to the field of cancer immunotherapy, it got me to think about it in a different way, and I think has kind of been therapeutic for me to reconcile my feelings about immunity,” said Peshoff.

A triple major in neuroscience, biology, and philosophy at Centenary College of Louisiana, Peshoff started her first research project as an undergraduate. The project focused on adenoviruses associated with Parkinson’s disease and introduced her to the field of neuroimmunology. At 24, Peshoff is now earning her doctorate in neuroscience and cancer biology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Having a primary immunodeficiency (PI) is the reason Peshoff decided to become a scientist. She grew up in a small Louisiana town. Her dad worked as a truck driver, and her mom was a janitor. She is the first generation in her family to attend college.

“Science was something that I never even knew existed until I started seeing the process as a patient, and [it] made me start to think about why humans develop diseases. It showed me that the field exists, but also that what happens in a lab can have an impact on people,” said Peshoff.

As a child, Peshoff got sick from viruses regularly, resulting in low-grade fevers and sore throats that could last for a month or two. Her pediatrician joked and called her illnesses the “Mekenzie virus.” At age 12, her doctor referred her to an immunologist who made the diagnosis.

“My parents were great advocates, and my pediatrician was amazing,” said Peshoff.

Prophylactic antibiotics failed to improve her condition, and she avoided immunoglobulin replacement therapy out of concern she would be exposed to pathogens in the infusion center. She lived with the infections for years until the spring of 2020, when her health improved.

“COVID was actually the healthiest I’ve ever been because it was the first time people started to think about how they affect immunocompromised people. It started making people care to wash their hands or stay home when they’re sick and protected me from a lot more than just COVID,” said Peshoff.

Peshoff chose to work in a research lab instead of direct patient care because it provides a safer working environment and allows her to make progress in scientific discoveries.

“Research scientists play a huge role in developing new therapeutics. While patient care is obviously an extremely important part of that, I think what we do is a little bit behind the scenes. But ultimately, what we do in the lab makes an impact on patients, too,” said Peshoff.

Peshoff and her family sought out the Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) just after her diagnosis to learn more about IgA deficiency, and she joined IDF Facebook communities when she got older to connect with others who have the same diagnosis.

“It made me feel like I wasn’t the only person in the world who was dealing with certain things,” said Peshoff.

She also participated in IDF advocacy work by contacting Texas legislators about banning copay accumulators and acted as a community liaison.

Peshoff disclosed her diagnosis to friends and family only when she began college and building her career. She was concerned that professors and employers might not consider her hardworking or dedicated to her profession. She’s since changed her mindset.

“When I started grad school, I started thinking about it differently because I realized that the commitment and passion that a Ph.D. requires is something I gained because of my diagnosis and my experiences, so I became more open about it and was willing to share my story with people,” said Peshoff.

Peshoff’s advice to other young people with PI starting college or a career is to consider the positives that grow from facing adversity.

“The strength you gain from living with a chronic diagnosis is a skill that few experiences can replace. I think you can use perseverance as an asset and also use the existential questions it brings up in yourself to find areas where you can impact other people’s lives,” said Peshoff.

“I would have never stopped to think, ‘What are the molecular pathways in the immune system that either promote or prevent disease?’ if I hadn’t been faced with that as a 12-year-old. And if I hadn’t thought about that, there’d be one less scientist thinking about it.”

Related resources

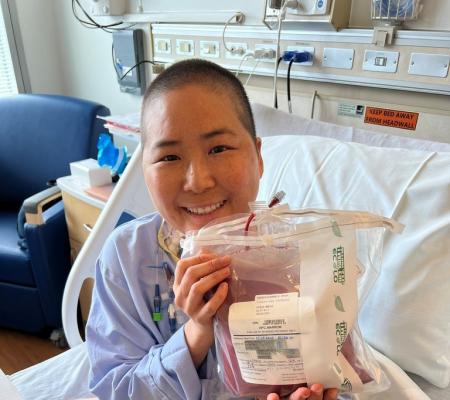

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.