-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

On some days, pain makes it almost impossible for Laura Zamora to get out of bed. She lives with holes in her esophagus that doctors monitor for cancer but can’t treat because surgery is risky. She needs a portion of her lung removed because of infection. She has fibromyalgia and scoliosis.

Zamora is diagnosed with one of the two most common forms of hyper IgE syndrome, a rare primary immunodeficiency that affects less than 1 out of a million people, with only about 250 cases recorded. She has a variant in the STAT3 gene, which causes a form of hyper IgE known as Job syndrome. The condition causes recurrent infections of the skin, ears, sinuses, and lungs, joint hypermobility, weakened bones, and organ damage.

“The hardest part for me in this disease is that I never know what's coming next. I think I take very good care of myself and it’s never enough,” said Zamora, 47. “But I’ve learned it’s about balance and pushing yourself when you can, and if you absolutely can't, respect it.”

Born in Mexico, Zamora developed skin problems and frequent infections as an infant. After a severe illness at age 2, her parents moved the family to the United States for better healthcare. When she was 4, a cold turned into a life-threatening infection. Zamora’s lung collapsed, and surgeons removed a third of it because the damage was so extensive. She required five more follow-up surgeries for repairs.

As a youngster, Zamora missed months of school and endured bullying from classmates who taunted her for being sick. She even experienced intolerance from some family members who thought her condition was contagious.

“Growing up that way is why I became so secretive. And I never talked about my illness. It was almost like I was always ashamed because of the things that I experienced,” she said.

Zamora received her hyper IgE diagnosis from specialists at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) at age 16. A year later, she had her son, Alexander, but during the birth doctors performed a procedure that caused her to develop sepsis. She held Alexander for about an hour before she spiked a fever and was rushed to the intensive care unit, where she stayed for two months, unable to see her baby.

“It was horrible,” said Zamora.

Zamora’s parents supported her and Alexander while she earned an associate degree. She found a job she loved but soon after, another infection required hospitalization. Doctors discovered tumors on her ovaries, and after surgery to remove them, they told her she wouldn’t be able to have any more children. She had to leave her job because of the extended illness.

“I fell into a depression. It was just heartbreaking for me, and I think at that point I had internal frustration and rebellion with a little bit of anger. I always thought, why me? I think that was the darkest time. Looking back, it's still a little bit hard. I didn't grow up with anybody around me that had any kind of illness whatsoever,” said Zamora, who has lost count of how many hospitalizations and surgeries she’s had.

A devoted Catholic, Zamora found strength in her faith, leaned on the resilience of her parents, and mustered the will to carry on for her son’s sake.

“After my depression, I came to the realization that my illness was here to stay. While I can do things to stay as ‘healthy’ as possible, I can't control my disease. But what I can control is my attitude. I realized that I had a choice to live positively and to choose happiness every day. Every day I still wake up, and I choose happiness,” said Zamora.

Doctors were wrong about Zamora’s reproductive health. She now has a second child, daughter Chloe Isabella, who is 14.

“She’s perfectly healthy,” said Zamora.

Since 2006, Zamora has worked as an assistant in the biology department at California State University, Sacramento where she helps graduate students with the application process. The position offers her the flexibility, and health benefits, she needs to navigate life with hyper IgE syndrome.

The types of medications that work to alleviate Zamora’s symptoms are limited. Most antibiotics are no longer effective or damage her teeth and gastrointestinal tract. She uses intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy, but it affects the function of her kidneys and other organs, so she takes breaks from it. She also uses antifungals, but sparingly because they also have side effects.

Zamora stressed that patients with hyper IgE should continually monitor their bone density because they are prone to developing skeletal issues. Two years ago, she fell in a sledding accident and fractured three vertebrae. Her surgeon said that osteopenia, which causes bone loss, in her back and untreated scoliosis caused the severe injury. She was unaware that she had either condition because two years before the accident, her bone density scan was normal.

“I sometimes use a cane and back brace due to the snow accident,” said Zamora.

Reflecting on her medical journey, Zamora recommends that teens and adults with chronic illness seek mental health support, an opportunity never offered to her in her younger years. She tries not to think about the medical trauma she’s experienced, and she focuses on what she can accomplish that day.

“For me, this is the only way I learned how to cope,” said Zamora.

Zamora said when she feels defeated, frustrated, angry, and overwhelmed, she allows herself two “cheat days” to feel those emotions.

“After my two days, I shake off my blues and get back to it. I have grit and am not a quitter. I love life. Despite everything that I have been through, I still have a real zest for life. I've learned to live and not just survive,” she said.

During the pandemic, Zamora attended Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) virtual events. She felt less isolated and appreciated being part of a community. She plans to attend the 2024 IDF Conference with her daughter.

“I hope I get to meet other patients like me, and even if I don't, I feel like I'm finally meeting my people,” she said.

Zamora wants to support others in their journeys with PI and instill in them the same hope that she carries in her heart.

"I just want other people to know that we were born with these terrible diseases, but at the same time, happiness is also our birthright. I firmly believe that. And I tell that to myself when I struggle. I deserve to be happy, just like anybody else," she said.

Walk for PI

The IDF Walk for Primary Immunodeficiency (PI) is an opportunity for communities across the U.S. to raise both funds and awareness for PI. At each event, you can form a team, join a team, register as an individual walker, or make a contribution.

Sign up to walkRelated resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

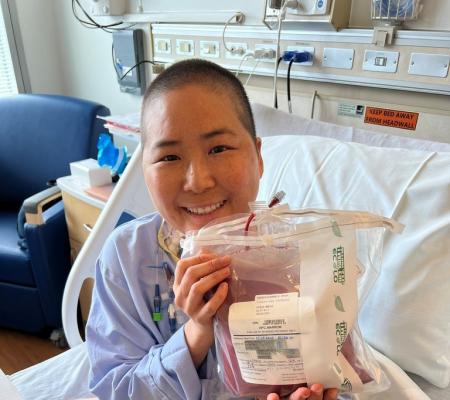

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.