-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Parents Marge Fujikawa and Irving Chew understood the gravity of their two sons’ diagnoses of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). They ensured their children received the proper care for their many infections, which sometimes meant spending weeks in the hospital, and administered their preventative medicine—injections of gamma interferon, antibiotics, and antifungals— eventually teaching them how to do it by themselves.

At the same time, they taught their sons to accept their diagnosis, appreciate the treatments available, and be respectful to the doctors. They approached their medical condition matter-of-factly and used hope to lessen the stress of sickness.

“We told our guys that your body is like a car. The car has to have frequent tune-ups, and that is when you go to the hospital to prevent you from getting sick. It’s preventative maintenance,” said Marge.

“We also told them please-and-thanks-yous are good, and the doctors will appreciate it. They are trying their best to help you, and they will want to help you more if you are nice to them. At their young age, they were cognizant that their lives were made easier with medications and support from doctors.”

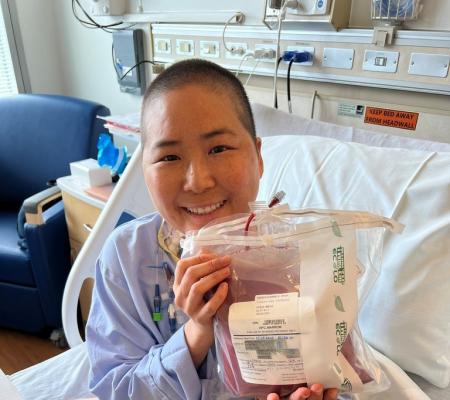

As adults, Marge Fujikawa's and Irving Chew's sons, Jason and Patrick Chew continued to put their faith in medical progress. Both sought more lasting curative treatment in 2017. Jason underwent gene therapy clinical trials at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), and Patrick received a bone marrow transplant through clinical trials at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The treatments provided them both with functioning immune systems, but in the following years, the brothers experienced different outcomes.

“I would not have picked both of them to go through this life-threatening procedure the same year, but they were adults, and they decided to do it, so the only thing we could do is to back them up,” said their mom.

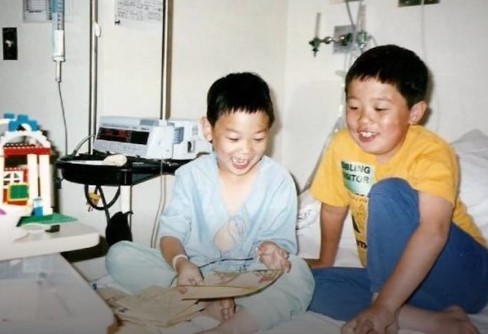

An active childhood

The family’s CGD diagnosis journey began when Patrick experienced poor health as a baby. Born on December 30, 1987, Patrick exhibited general malaise, anemia, and granulomas in the colon. The pediatrician lacked the experience to coordinate his care and Marge’s University of California Berkley professor at the time (she was earning her doctorate in nutrition) said that he thought it might be due to an unknown infection.

The Chews sought a second opinion from a pediatric immunologist at University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Patrick received a diagnosis of CGD at 11 months old. His parents learned the value of advocacy in dealing with rare diseases like CGD, and were thankful for UCSF's expertise.

“Don’t let doctors disregard your opinion. If we had, we may have lost our first son,” said their mom.

The Chews hoped that their second son Jason could be a bone marrow donor for Patrick. Bone marrow transplant (BMT) is a curative option for CGD. But Jason received a CGD diagnosis too, one month after he was born on January 14, 1990.

Throughout childhood, the boys developed repeated bacterial and fungal infections in their ears, lungs, and intestines, had pneumonia numerous times, required surgery to remove nodes, and frequently experienced long stays in the hospital, from a few days to a few weeks.

Despite their illness, the boys thrived when well, playing baseball and soccer, learning how to swim, riding bikes, and enjoying Cub Scouts. They maintained a positive attitude through it all.

“They stayed active. I told them when you can do your best, do it. When you can’t, you can’t,” said Marge, who stayed at home to care for the children and act as medical liaison while dad worked. “They appreciated life so much more, and I could deal with their conditions because I knew they were going to get healthy in between. I would say, ‘Hey, this is a challenge, but we can deal with it.’”

Patrick said having Jason by his side made it much easier to cope with CGD during their younger years.

“It is because he was with me every step, being my best friend and playmate, that CGD in my early years wasn’t as daunting, that my childhood was fairly ‘normal,’" said Patrick.

“I think one of our favorite memories is the time we were both hospitalized at the same time for different things. We were in elementary school, and it was ‘cool’ that we managed to get that sick at the same time. Even growing up we compared illnesses, ‘You had pneumonia five times? Well, I had a stomach bug that gave me ulcers.’”

After major hospitalizations in middle school, Jason and Patrick remained mostly well in high school. Jason learned archery and snowboarding, played high school baseball, and became a crew coxswain for the Pacific Rowing Club. Although illness prevented Jason from finishing college, he earned his credential as a physical trainer through the National Academy of Sports Medicine, helping others get in shape. Patrick concentrated on his studies, earning straight As and participating in mock trial, student government, and biking club. He double majored at the University of California Berkley and earned his master's degree from the University of Chicago.

A challenging adulthood

After high school, Jason took responsibility for his own healthcare, and at age 20, he started losing weight and experiencing pain in his stomach. In 2012, doctors diagnosed him with fatty liver disease.

Jason’s diagnosis proved to be a turning point in both young men’s healthcare.

Marge accompanied Jason to the surgery consultation and learned that an intern, with no CGD patient experience, was slated to perform the surgery. She advised against it, and instead set up an appointment with a doctor at the NIH who had treated nine CGD patients and performed liver surgery on over 200 people.

“I have learned, ever since the kids were small, that you have to advocate. You have to keep pushing. You know your kids more than the doctors,” she said.

Jason underwent surgery at the NIH in the summer of 2012, and though it seemed touch and go, he pulled through. He also became an established patient at NIH, which entitled him to one free trip and check-up annually at the facility. In 2013, Patrick accompanied Jason, and both became patients at NIH. For years, every summer they traveled together for their check-ups.

In 2016, NIH doctors suggested they consider BMT as a treatment. At the forefront of research on CGD, NIH found that patients didn’t need familial tissue matches for a successful BMT.

Doctors located three BMT matches for Patrick in a worldwide search, but none for Jason, so the younger brother opted for gene therapy clinical trials at UCLA.

“NIH was data-driven. They realized that two percent of people die every year from CGD. When you go down by two percent every year by the time you are 30, close to 60 percent of people in their age group with CGD are dead. Every year your cohort is two percent less,” said Marge.

“NIH, to their credit, they don’t talk down to you; they’ll talk to you at the level of your understanding so with Patrick they were very upfront with it because they knew he could take it.”

In a diary he kept and hoped to share with other CGD patients someday, Patrick said it only made sense to take the chance with BMT because his disease would only worsen with age.

“Among the lines that (my doctor) used to convince me was that 'The younger you are, the better a chance the graft has to repair damage caused by past infections' and 'There is a chance that a transplant can even take care of my autoimmune issues.' Considering my main issue for the past several years had been autoimmune issues, and that I was not going to get any younger, those had been some pretty convincing lines. The fact that their success rate has also been high more or less clinched the deal for me,” wrote Patrick.

Both Patrick’s and Jason’s treatments proved successful, and the brothers were no longer considered immune deficient post-treatment, but because of previous lung damage due to extensive infections, Jason's health declined.

“The treatment itself worked but what you have to realize is that by the time they got that treatment, one was 27 and the other was 29. Their bodies had already gone through a lot of trauma. They were no longer considered immunodeficient. That part was considered successful. But what they don’t tell you and what they didn’t know was how much the trauma had affected their health,” explained Marge.

“The treatment didn’t go back and treat the previous traumas. Whatever conditions you have, you are stuck with already, so that is what led to a gradual downfall for Jason. Both of his lungs had been very stressed.”

Jason passed away on July 27, 2020.

Jason is remembered as a happy-go-lucky person who lived by the motto, “Treat others as you want to be treated,” said his mother. He was well-liked, and his infectious smile brought joy to others.

Jason lived a full life and pursued a variety of interests and hobbies during his time as a young adult. An excellent cook, he became an expert in nutrition. He traveled to Hawaii where he learned to surf and kayak. He lifted weights and took college courses in kinesthetics and psychology. He joined a swing dance club and participated in dance showcases. He enjoyed nature photography. And he gave back to the community by volunteering for Special Olympics and the IDF Teen Program.

“Jason's life was a gift. His life enriched all who knew him. He understood the importance of communicating, showing appreciation, and projecting positive vibes. In his lifetime, he had the chance to love, develop enduring friendships, and experience so many different interests,” said Marge.

Patrick said his CGD diagnosis, and the loss of his brother have given him perspective and nurtured a deep sense of gratitude.

“Living with CGD definitely shaped who I am and how I see the world, but it has also given me empathy, patience, and an appreciation for life,” said Patrick.

“I am grateful especially for my parents, who went through endless stresses with my brother and me. And though my brother passed away from complications created by his CGD, I will also be eternally grateful to him for accompanying me through his thirty years of life.”

___________________________________________________________

Read more about Patrick Chew's journey with CGD.

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.