-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

For over a year, Diane Mato repeatedly took her toddler son Nicholas to doctors because of fevers that lasted weeks and severe urological problems that required a painful scope in his bladder and a catheter.

When symptoms returned despite the medical procedures and treatment with oral and injectable antibiotics and steroids, Diane Mato had enough. She put 3-year-old Nicholas in the car, loaded up her backpack with books, food, and clothes, and headed to the emergency room at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

There, a pediatric infectious disease specialist suggested they stay the week while doctors ran tests. A biopsy of Nicholas’s swollen lymph node revealed an unusual bacterium, but other tests for diseases like cat scratch fever proved negative. Doctors sent them home on a Friday.

Monday morning, the hospital called.

“It was serious enough that they wanted him to come back right away,” said Mato.

On March 9, 2002, the medical team at Lurie diagnosed Nicholas with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a primary immunodeficiency (PI) in which a person lacks an enzyme in white blood cells responsible for killing certain bacteria and fungi.

“I was shocked,” said Mato. “The doctors thanked us for keeping Nicholas alive, for being persistent and advocating for him, and he landed in the best place. I’m so thankful for Lurie.”

After Nicholas’s diagnosis, the Matos learned that their youngest son Eric, an infant at the time, also has CGD, and their eldest, Adrian, does not have CGD.

One month after the diagnosis, the family, who resides in Chicago, traveled to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland where they learned more about CGD, and doctors ran additional tests. Doctors prescribed injections of interferon-gamma three times a week, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, and an antifungal.

“After a long and confusing period of illness with peaks and valleys of chronic and acute infections, our journey took us to NIH, one of the largest research groups that focus on CGD, and we were fortunate that our sons received such expert care,” said Mato.

One of the greatest challenges of raising two boys with CGD was keeping them safe while still allowing them to be active, said Diane Mato. The Matos didn’t allow the boys to swim in freshwater lakes or take school trips to the zoo, but they did encourage them to join in team sports like baseball, basketball, and football.

“A lot of people are different in how they respond. We are not fanatical parents. You have to have that balance, everything in moderation. I can’t keep my kids in a bubble,” she said.

The Matos focused on making changes at school to benefit their children. Diane Mato actively lobbied the local school administration to replace the playground surface material made of woodchips, which contained dangerous fungal spores, with a rubberized surface. She also sought help from physicians in making her case that her sons should be provided with learning accommodation plans at school.

Being an advocate for your children in the school setting is crucial to not only protect them but to allow them to be treated the same as other children so that they don’t feel so isolated, said Mato.

“I really want to stress that,” she said.

Mato said that when her boys were young, she and her husband built a routine around taking their medication, and it helped. As their sons moved into their teen years, the Matos, under physician supervision, allowed their sons to phase out the interferon-gamma injections, which had caused side effects over the years such as fevers, chills, and body aches.

Today, the Mato brothers remain healthy. Nicholas, 23, is a supervisor at UPS and is completing his associate degree, with plans to earn a bachelor’s degree in business from the University of Illinois. Eric, 20, works part-time in the summers at Park Ridge Community Bank and is completing his undergraduate degree in marketing at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee.

“Their immune systems are functioning pretty good right now,” said their mom, adding that while they are not currently candidates for bone marrow transplant, they would consider gene therapy as an option for treatment in the future.

Mato has relied on IDF for support and information, particularly material related to advocacy in education, throughout her sons’ diagnoses. Her family attended IDF conferences, and she participated as a panel member during a session on CGD. IDF offered connections with other families and a greater understanding of CGD.

“It was very empowering,” said Mato of her experiences with IDF.

Mato said the best way to prepare children with CGD to transition from childhood to young adulthood is to be organized, follow routines, and maintain ties with providers.

“You can let go a little bit but keep that strong communication with your doctors and the academic team. It really helped our family tremendously,” said Mato. “There is light at the end of the tunnel.”

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

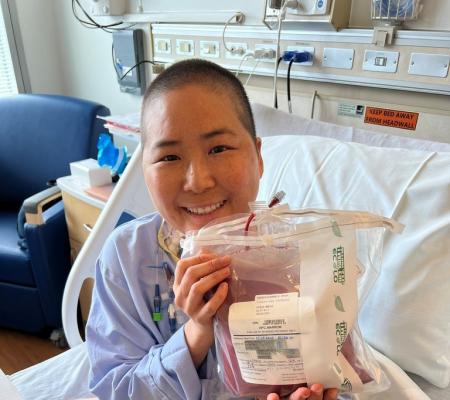

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.