-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Kathi Narlock still has the meticulous notes she kept on every fever, illness, medication, treatment, and diagnostic test her son Nick Narlock experienced during his childhood. Diagnosed with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) as an infant, Narlock required hospitalization over a dozen times. His hospital stays lasted days to months and were primarily for lung infections and gastric outlet obstructions, which prevent food from moving from the stomach into the small intestines.

Though he had periods of good health in his teens and 20s, infection always returned, and Narlock finally chose a bone marrow transplant treatment in spring 2022 at age 32.

“Everything worked out really well for him. Even though he had little bumps along the road, he did extremely well,” said Kathi Narlock, who aims to share a message of hope to families coping with CGD. “I want people to know that kids can get through this.”

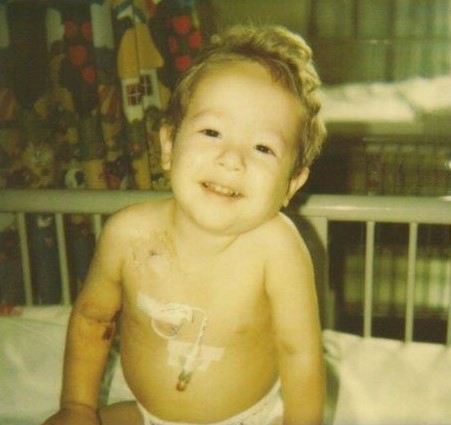

The Narlock family’s journey with CGD began in April 1990 when Nick Narlock, a newborn, regularly vomited his formula and slept more than normal. Doctors diagnosed him with immune thrombocytopenic purpura, which meant he had low numbers of platelets that resulted in internal bleeding. Although the hospitalization allowed rest and recovery, it didn’t provide definitive answers.

“We were exhausted. We had no idea what caused it, and there was nothing we could do,” said Kathi Narlock.

Swollen lymph nodes prompted Nick Narlock’s next visit to the hospital when he was about a year old. After he didn’t respond to three rounds of antibiotics, doctors performed surgery to remove what they thought were infected lymph nodes. Instead, they found solid masses and sent him home with intravenous antibiotics.

A few weeks later, a letter arrived in the mail, delivering the news that doctors suspected CGD because the biopsy yielded a rare bacterial infection. Narlock returned to the hospital for three nitroblue tetrazolium tests (NTB) to confirm the diagnosis.

“I don’t think they wanted to believe it,” said Kathi Narlock, referring to her son’s doctors.

Because Nick Narlock’s father, Rick Narlock, served in the Air Force, the family traveled to a healthcare facility on a military base in San Antonio, Texas, for a second opinion. Doctors confirmed the diagnosis and started Narlock on preventative antibiotics and shots of gamma interferon three times a week. The Air Force base in Missouri, where they lived then, transferred Rick Narlock to the base in Texas so his son could have the proper care.

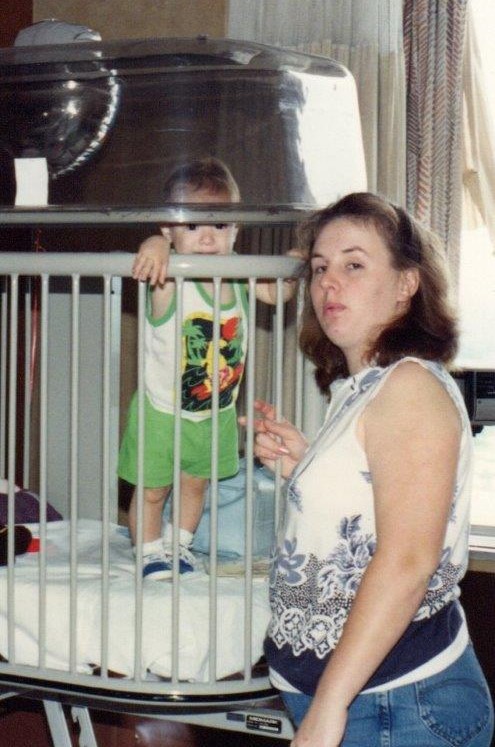

The toddler’s health didn’t stabilize for long. In May 1992, doctors administered IV antibiotics to treat yet another enlarged lymph node, performed surgery to biopsy the lymph node, and placed a central line to administer medication for several months. In October, Narlock, suffering from a fever and pain in the naval area, underwent more surgery to remove nodes from the folds of his intestines and received another central line.

During his hospitalizations, Kathi Narlock stayed with her son while Rick Narlock cared for their other son Stephen, three years older and in elementary school. Narlock recalls how her husband and son visited nightly to share dinner, and on weekends her husband relieved her in the hospital. Sharing meals and coordinating care for the boys brought the family closer.

“I didn’t work, and I was basically Nick’s sole caregiver, but I still had help. My husband is very supportive,” said Narlock, in her mid-20s at the time of her son’s numerous hospitalizations as a young child.

Always their son’s advocates, the Narlocks faced one of many significant challenges when he developed a gastric outlet obstruction in February 1993. The condition caused Nick Narlock to vomit everything he ate because of a blockage from the stomach to the small intestine. Kathi Narlock knew that a steroid would help because the mother of another child with CGD, Mary Hurley, well-known in the CGD community, had sent Narlock research papers detailing the success of such treatment. Doctors disagreed, but Narlock kept pushing and showed them the research paper.

“They didn’t want to listen to me that prednisone would take care of the obstruction, and finally, I got them to try it,” said Narlock. “They crushed some up in applesauce, and Nick threw it up but kept enough down that it worked. When he finally could eat, the first thing he wanted was chicken nuggets from McDonald’s.”

Doctors used steroids again for several months in the winter of 1994-1995 to treat a bladder granuloma that Narlock developed and again in November 1995 when he experienced another gastric obstruction. Kathi Narlock said before the internet provided resources, families connecting with each other through telephone and mail provided support, including medical information.

“I wasn’t prepared at all (for the CGD diagnosis). I just went with the flow, and I tried to find the information myself,” said Kathi Narlock. “My mom paid the money for a list from a rare disease organization, and she sent letters to two dozen people, and she heard back from two, and that is how we met Mary Hurley.”

During Rick Narlock’s tour in Korea from May 1994 to May 1995, miraculously, his son didn’t require hospitalization. But as soon as he returned, the family had to wrangle with the military not to get transferred to Turkey.

“Once they got to volume two of Nick’s medical records and saw that he had an immune deficiency, I knew we weren’t going to Turkey. And they canceled the orders,” said Kathi Narlock. The family eventually found an immunologist stationed at a base in Omaha, Nebraska, where they moved and still reside today.

After a few visits to a CGD specialist in California, Kathi Narlock enrolled her son in an anti-fungal study at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the summer of 1997. A follow-up appointment at the NIH in November saved Nick Narlock’s life.

“You couldn’t tell anything was wrong; there were no fevers. They did a chest x-ray, and they did lab work, and we figured we were going home,” said Kathi Narlock. “The next day, I’m sitting in the hospital with him, and this woman comes up to me and says, ‘I’ll be with Nick during his procedure,’ and I said, ‘What procedure?’ and she said, ‘They haven’t talked to you? I’ll be back,’ and I said, ‘What’s going on?’”

“And the doctor said that he had lung infections in three out of the five lobes in the lungs. But he had no problems breathing, no shortness of breath, nothing. If we had not been there, he probably wouldn’t be with us. He was very fortunate.”

Doctors treated him with antifungals, antibiotics, and white blood cells. One doctor suggested removing the infected lobes, but Kathi Narlock protested.

“I didn’t want him to go through that if it wasn’t necessary,” said Narlock.

Nick Narlock received regular care at the NIH, traveling there every three months and then every six months. At age 12, he battled another gastric obstruction and lung infection with the help of doctors at NIH.

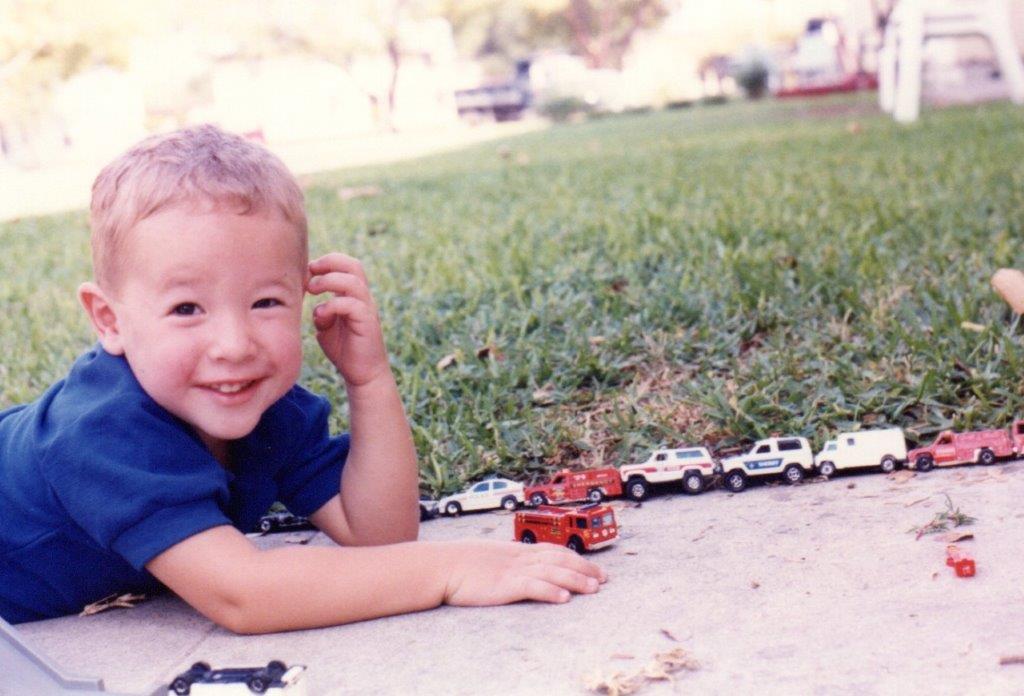

Kathi Narlock said that she kept his school and teachers apprised of his health every year, but beyond making sure he didn’t touch any live animals in classrooms and ensuring that he washed his hands after being out on the playground, she didn’t request accommodations.

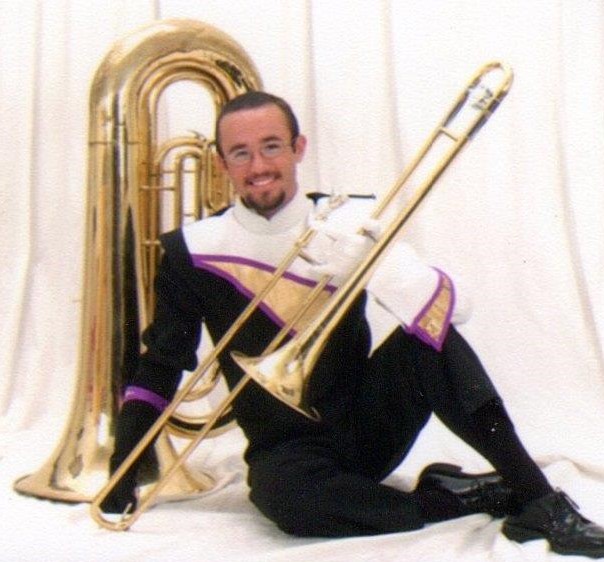

CGD didn’t stop Narlock from playing soccer, trying martial arts, joining Scouts, fishing, or visiting the pumpkin patch and zoo. In high school, he played tuba, trombone, and saxophone.

“He’s just been just terrific through the whole thing. He likes to fish, and when they were little, he wore rubber gloves and boots, and we wouldn’t let him touch fish,” said Kathi Narlock. “We didn’t stop what we were doing because of his disease. He did not live in a bubble.”

In November 2021, about a year after Nick Narlock had recovered from a staph infection and Bell’s palsy, doctors told him that if he didn’t undergo a bone marrow transplant (BMT) soon, his age would make it less effective.

Narlock gave up his apartment in Omaha in April 2022, drove across the country, and settled into an Airbnb as his new home while preparing for a BMT at the NIH. His mother followed a week later to be his NIH-required caretaker.

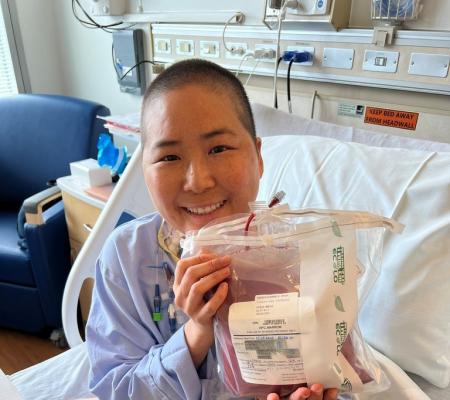

On May 15, 2022, Narlock received four bags of stem cells from a donor in Germany, an almost perfect match. He handled the conditioning with chemotherapy and radiation before the procedure and chemotherapy after the BMT well, said his mother, and didn’t experience graft versus host disease. When he left the hospital, Narlock had 100 percent engraftment.

There were tough days, with exhaustion and headaches, but overall, Narlock recovered successfully after the transplant and drove back home cross-country with his father in August.

Kathi Narlock said the most important advice she would give families coping with CGD is to follow their instincts regarding treatment decisions, even if they conflict with what is recommended by doctors.

“Advocate if something seems wrong, but the doctors say that’s nothing. You have to push to have it checked out more,” said Narlock.

“With Nick, I wasn’t going to wait for it to get to the point where he is really sick. If you’re not going to help, I have to find someone who will.”

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309