-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has one of the largest single-center groups of persons in the world who have undergone bone marrow transplants for chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) in clinical trials, serving as an important resource for those diagnosed with CGD.

At the Immune Deficiency Foundation’s (IDF) 2022 Primary Immunodeficiency (PI) Conference, Dr. Elizabeth Kang reviewed past and current NIH bone marrow transplant (BMT) clinical trials for CGD during her presentation, “The ABC’s of CGD.” Kang is the chief of the NIH Chemotherapeutics Unit of the Genetic Immunotherapy Section at the Laboratory of Clinical Immunology and Microbiology.

People with CGD don’t produce enough superoxide in their white blood cells to fight infections caused by certain bacteria and fungi. They battle chronic infections in the skin, lungs, lymph nodes, liver, and bone that lead to frequent hospitalizations and long-term damage to organs. Patients may have scarred lungs or require liver surgery to remove abscesses. They are also subject to high rates of autoinflammatory diseases affecting the colon (colitis), joints (arthritis), and lungs (pneumonitis), and their cells lump together to form granulomas, which can block the urinary tract or esophagus.

Standard treatment includes daily antibiotics and antifungals, steroids, gamma interferon injections three times a week, and routine CT scans to check for asymptomatic infections. However, infections still occur, and the medicine can cause complications.

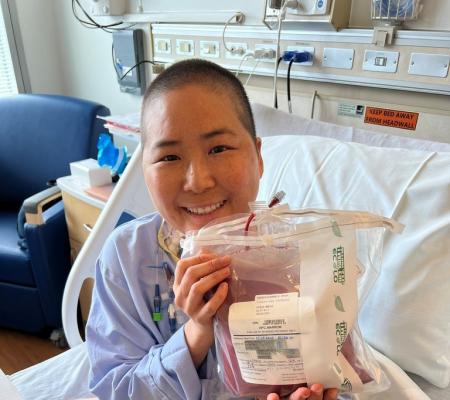

To find a more long-term, curative treatment approach to CGD, researchers have explored BMT in clinical trials. BMT replaces the stem cells that give rise to white blood cells with low or no superoxide in a person with CGD with healthy donor stem cells that grow into a normal immune system.

In trials that began in 2016 and are still enrolling, NIH researchers administered a conditioning regimen of chemotherapy and other immune-suppressing drugs before the transplant, a high stem cell dose at the time of transplant, and a post-transplant chemotherapy drug. The goal was to prevent graft failure and graft versus host disease (GVHD).

Kang said the NIH learned from BMT trials for CGD that took place in 2007 and adjusted the 2016 trials.

“From the protocol in 2007, the major complication in the transplant was not GVHD, which is when donor cells attack the patient, but actually a propensity to reject the graft or graft failure, and when we had graft failure, we tried to salvage the grafts by giving infusions of donor cells or more transplant cells, and then we ended up with GVHD and more complications,” explained Kang.

So far in the 2016 trials, the NIH has transplanted 37 patients – 5 females and 32 males – between the ages of 5 and 58 years old, some of whom have one or more pre-existing infections or health conditions. The results of the study are promising.

The trials show a 96 percent survival rate – one person died from underlying lung disease – and 93 percent of people in the trial had no complications from the treatment (there was some graft failure). Infections resolved in all patients except one in whom infection improved but was not cleared at the time of discharge. Pneumonitis, which can be a condition preventing other centers from doing a BMT, improved significantly and colitis improved by three to six months in all patients.

“Resolution of inflammation and/or infection will still take time even with successful engraftment,” said Kang. “Patients still have to stay on their antibiotics and antifungals, but usually, within six months to a year, it’s all gone.”

Researchers continue to adjust their study design and have added another immunosuppressant drug and replaced part of the chemotherapy drugs with an antibody.

“The idea is that as we improve on transplant and we get better engraftment, we want to continue to try and improve on toxicity or reduce toxicity and if we could replace the busulfan with an antibody that is a protein that doesn’t cause the same kind of damage that busulfan will, even at lower doses, then we think that we are doing a benefit,” said Kang.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309