-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Three years ago, Chris Simpson weighed his options. Doctors had just diagnosed him with CD40 ligand (CD40L) deficiency, also known as X-linked hyper IgM syndrome, a rare and life-threatening primary immunodeficiency (PI), after he had lived for 35 years thinking he had common variable immune deficiency (CVID). Decades of infections caused severe liver and lung disease, gastrointestinal problems, weight loss, malnutrition, and fatigue. Simpson knew he’d lived longer than most people with his condition.

“One solution was to do both a liver transplant and a bone marrow transplant, both of which required donors. Another approach was to do nothing—roll the dice and keep living my life the way I’m living it. The way the doctors explained it was that I was like a ticking time bomb but with no countdown clock,” said Simpson. “I was fortunate to be alive with [X-linked] hyper IgM at my age and being in the state I was in.”

Simpson embraced a physical fitness routine to strengthen his body and prepare for whichever path he chose. He followed a careful diet, joined a CrossFit gym, and eventually became a CrossFit trainer.

While Simpson focused on building his stamina, his doctors debated how to proceed. They also put him in touch with the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH proposed treatment option number three—gene therapy.

In the winter of 2024, NIH researchers asked Simpson if he’d be interested in a clinical trial testing gene therapy as a curative treatment for CD40L deficiency. The trial used a type of gene therapy called base editing. For base editing, cells are taken from the patient, the editing machinery makes a single letter change to cells’ DNA to correct the PI-causing variant, and the cells are returned to the patient. The changed cells returned to Simpson would no longer contain the variant in the CD40L gene that causes X-linked hyper IgM. If it worked, Simpson would have a functioning immune system using his own corrected stem cells.

“The idea is that one day they can use the process of gene editing to help people with other genetic disorders,” explained Simpson.

The journey to a CD40L deficiency diagnosis

Simpson doesn’t remember a time when he wasn’t ill.

“I was severely sick as a child. I lived at the hospital, sometimes for months at a time, almost a year at a time,” said Simpson. He was diagnosed with CVID at age 2. “During that time, there were multiple stints where my parents were told they didn’t think that I was going to make it out of the hospital because of the severe infections.”

Despite monthly treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy, Simpson struggled with sickness and had a constant cough. He considered high school a healthy time because he only had a few cases of pneumonia that required hospitalization.

In his 20s, Simpson underwent surgery to treat a severe liver problem. Doctors diagnosed his condition as primary sclerosing cholangitis, a potentially fatal liver disease. Simpson suspects it was caused by a Cryptosporidium infection, a parasite to which people with CD40L deficiency are vulnerable.

“It should have killed me both times when I got hospitalized for it. They didn’t think I was going to make it out,” said Simpson.

Simpson attended college and built a career managing grain imports and exports for the global market, a job he could do at home. At the same time, he juggled appointments with several medical specialists.

“No one really knew what to do,” said Simpson.

Despite protest from his family and friends, Simpson left his care team in Texas to move to Southern California for his job. He connected with doctors there, but his health declined.

One day, after getting off the night shift, he felt terrible and visited the emergency room. Doctors diagnosed him with malnourishment and celiac disease, an autoimmune condition that causes damage to the small intestine. He called on family to come out and help him. He received an emergency blood transfusion and recovered but had a difficult time gaining weight.

After another work move to Minnesota, and another care team later, Simpson learned he had developed permanent lung damage from the many cases of pneumonia and bronchitis. Doctors continued to monitor his liver and celiac disease, and became concerned about a possible autoimmune disease when he developed warts. Just as doctors urged him to get genetic testing, work transferred Simpson back to his home state of Texas.

Simpson connected with doctors at University of Texas Southwestern Medical. Within six months, they diagnosed him with CD40L deficiency. Learning his correct diagnosis at 35 left Simpson with a lot to process.

“When I was told I have [X-linked] hyper IgM, which is more severe than CVID, and statistically I shouldn’t be alive, it gave me clarity,” said Simpson.

Curative but experimental gene therapy

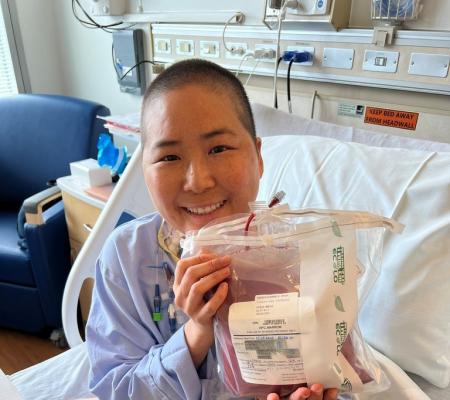

Simpson arrived at the NIH for gene therapy treatment in July 2025 and expected to stay for about two months. Doctors planned to provide Simpson with base-edited hematopoietic stem cells first, followed by base-edited T cells, a short-term treatment to lower the risk of infection.

“The ability to give edited T cells is critical in ensuring Chris’s safety because of the time it normally takes for T cells to develop from the corrected stem cells. So, these edited T cells provide a critical bridge to the arrival of the rest of the troop, which are the corrected T cells that arise from his corrected stem cells,” explained NIH Gene Therapy Development Unit Chief and clinical trial principal investigator Dr. Suk See De Ravin.

Much like the rest of Simpson’s health journey, however, unexpected medical issues changed the direction of the treatment. Conditioning with chemotherapy and other drugs, administered before the treatment, caused his liver infection to worsen. He developed an ulcer and internal bleeding. Then, Simpson navigated a case of COVID-19.

In response to Simpson’s decline, doctors reversed the order of the protocol. They gave him two infusions of the base-edited T cells before administering the stem cells. It worked.

“I’m not putting this lightly. That saved my life,” said Simpson. “It was a miracle.”

Doctors provided the base-edited stem cells in mid-September and then three more doses of the base-edited T cells before he left in October. Every six weeks he returns to the NIH for additional T cell infusions.

Simpson is the first person to ever have this type of gene therapy using both base-edited stem cells and base-edited T cells and the first with CD40L deficiency to receive gene therapy of any type. He is now 92% engrafted with the corrected stem cells, which means most of Simpson’s stem cells don’t contain the variant in the CD40L gene that causes X-linked hyper IgM. Doctors consider the treatment a success.

“If we can take a patient like me and fix him, well then, we have the opportunity to really change protocol going forward for a lot of people,” said Simpson.

Simpson said he could never have come through the treatment without the dedicated support of the staff at the NIH.

“They would get me out of my room, walk me around, they would keep me busy, keep me company. This was an all-hands-on-deck treatment and I’m very appreciative of everyone who stepped up,” said Simpson.

A more open outlook

Before learning he had CD40L deficiency, Simpson kept his CVID diagnosis mostly to himself. He rode a rollercoaster of illness and fatigue alone. He didn’t share details with colleagues at work, and limited what he told family and friends

With the CD40L deficiency diagnosis, he became more honest with others about his health, and embraced opportunities to both deepen his knowledge of PI and tell his story.

“My diagnosis led me back to IDF. I wanted to reach out and learn more. Was there something I could do to get plugged in and learn? Was there something I could do to help?” said Simpson.

He volunteered at Cook’s Children’s Medical Center, where he spent 25 years as a patient, by speaking to the families of children with compromised immune systems. He shared his health journey to inspire hope in families that their children, too, could push through their illness and live a full life. He also shared his story in a podcast with the Hyper IgM Foundation and volunteered to lead a Get Connected Group for men.

“No one really, truly knows the struggles unless you're talking to other patients who are very aware of what you have to go through on a day-to-day basis,” said Simpson.

Simpson remains in isolation at home as his immune system recovers. He receives visits from family and friends when they are healthy. He is back to working. He finds purpose in opening up about his health journey.

“Learning from someone who has PI what their struggles are and what they had to overcome can help others who don’t have a chronic illness put things into perspective. That has been a big wake-up call for me—to be OK to share and also learn from others about how they cope, and what they do with their struggles,” said Simpson.

Simpson said most days are good, but he does have moments when he is overwhelmed by the future because his health is so unpredictable. He reminds himself to focus on things he can control and confide in family, friends, and mentors to get him through the tough times.

“I’ve always liked to stay in the dark, and I just don’t think I can do that anymore,” said Simpson.

2026 PI Conference

Join us June 25-27, 2026, in San Antonio, Texas, for a transformative experience where stories connect, voices unite, and journeys inspire. No matter where you are in your primary immunodeficiency journey, access expert-led education, meaningful connections, and cutting-edge insights from world-renowned immunologists.

Register nowRelated resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309