-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

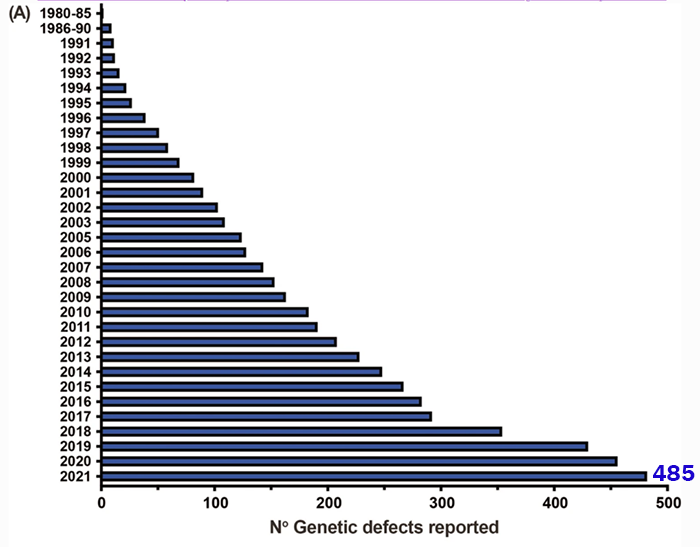

Research Grant Program

Every few years, the Inborn Errors of Immunity (IEI) Committee of the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) combs through scientific reports to revise its list of genetic variants that cause inborn errors of immunity, also known as primary immunodeficiencies (PIs). The latest classification, published in June 2022, adds 56 new PIs to the list, bringing the total to 485 distinct disorders in 10 categories.

How are new disorders added?

By definition, PIs are inherited disorders in which part of the immune system is missing or does not function properly. How does the IUIS committee decide which disorders meet this definition?

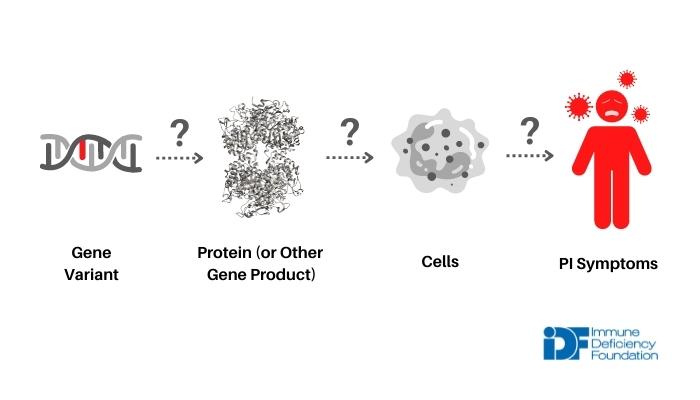

Each of the 56 newly added disorders had to fulfill three criteria. The criteria ensure that only disorders with strong evidence linking a single genetic cause to patients’ symptoms make it onto the list.

- The disorder is caused by a genetic variant in a single gene, and that variant does not occur in individuals who do not have PI.

- Research studies show that the genetic variant affects either the amount or function of the protein (or other gene product) that the gene codes for. This type of evidence is important for making sure that the variant is actually responsible for a change beyond just the gene itself.

- Studies also show that the genetic variant ultimately changes the number, function, or behavior of cells in a way that makes sense given patients’ symptoms. Again, this type of evidence links the variant to a larger biological change.

immunodeficiency by looking at its effect on the protein (or other gene product) and on cells.

Why does the list of IEIs/PIs keep expanding?

The overall number of IEIs/PIs recognized by the IUIS committee has climbed exponentially over the last several years.

Adapted from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-022-01289-3.

In the past, PIs were classified by their symptoms, their pattern of inheritance, and the results of laboratory tests measuring components of the immune system , like immunoglobulin levels or the number of circulating B cells. All of these factors are still important in diagnosis. However, PIs with identical symptoms and patterns of inheritance can have different genetic causes.

Because of the rise of genetic testing, researchers and clinicians can now tease apart similar disorders. For example, autosomal recessive (AR) agammaglobulinemia (absence of antibodies) with missing B cells can be caused by variants in five different genes: IGHM, IGLL1, CD79A, CD79B, and BLNK. Since the basis of the committee’s IEI/PI classification is the genetic cause of a disorder, AR agammaglobulinemia is actually considered a collection of five different disorders. So, the more researchers learn about the genetic causes of IEI/PI, the longer the list gets.

Knowing the genetic cause of PI symptoms may not impact patient care or treatment now—after all, treatment for patients with agammaglobulinemia, regardless of cause, is currently immunoglobulin replacement therapy. However, as more ‘ precision medicine’ treatments like targeted drugs or gene therapies are developed, knowing exactly which genetic variant is causing symptoms will be important.

Interestingly, several disorders, like common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), are included in the IEI/PI list even though their cause remains unknown. These disorders, which are largely in the primarily antibody deficiencies category, were discovered prior to the availability of genetic testing and are thought to be genetic, but the gene variant or variants responsible have not yet been identified. As with AR agammaglobulinemia, it is possible that these will turn out to be a collection of similar disorders with several different underlying causes.

Different variants in the same gene cause different PIs

Just as the same PI symptoms can involve different genes, the same gene can be involved in different PIs. There are 40 genes that appear in the list of IEIs/PIs more than once because different variants within them cause different types of PI.

The IFIH1 gene is a good example. Some IFIH1 variants lead to deficiency, or lack of, functional MDA5 protein. Since MDA5 activates the immune system when it encounters certain viruses, symptoms of MDA5 deficiency include recurrent and severe infections with RNA viruses like rhinovirus (common cold) or influenza virus (the flu) . In contrast, other IFIH1 variants cause Aicardi-Goutières syndrome 7 (AGS7), a severe autoinflammatory disorder with progressive neurological and autoimmune symptoms.

IFIH1 variants that cause MDA5 deficiency are relatively straightforward—if you inherit one from each parent, you lack functional MDA5 protein, can’t detect double-stranded RNA from an infecting virus, and can’t turn on the type 1 interferon pathway in response. The type 1 interferon pathway is a critical first-line (or innate) immune response against viruses that promotes inflammation, turns on genes in infected cells that keep the virus from making copies of itself, and communicates the threat to neighboring, uninfected cells. When the type 1 interferon pathway is interrupted, the virus gets a leg up and causes more damage and a more severe infection than in someone with functional MDA5 protein.

On the other hand, if MDA5 is overactive and triggers the type 1 interferon pathway when there’s no viral RNA around, the resulting inflammation can do a lot of damage. Both the neurological and autoimmune symptoms of AGS7 result from inappropriate, chronic activation of type 1 interferons.

New PI discovered from cases of severe COVID-19

Without the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the new disorders added to the IEI/PI list may not have been discovered: toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 deficiency.

Early in the pandemic, public health officials noticed that, among those under 60, men are at higher risk of severe COVID-19 than women. A group of researchers investigating this observation found that 1.8% of men under age 60 with severe COVID-19 had rare variants in the TLR7 gene on the X chromosome. These variants left individuals without functional TLR7 protein.

Like MAD5, the TLR7 protein detects certain viruses and triggers an antiviral response through the type I interferon pathway of the innate immune system. In individuals with TLR7 deficiency, lack of TLR7 protein means no type I interferon response, so the SARS-CoV-2 virus is able to copy itself and infect other cells without much resistance. The result is severe cases of COVID-19.

How does TLR7 deficiency relate to a higher risk of severe COVID-19 in men? Variants causing TLR7 deficiency are inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern—men inherit only one copy of the TLR7 gene from their mothers, while women inherit two copies, one from each parent. As a result, TLR7 deficiency and its symptoms (severe COVID-19, in this case) are much more likely to be seen in men.

It is surprising that TLR7 deficiency was not picked up as a cause of severe viral infections before the pandemic. It’s possible that TLR7 deficiency only makes a person susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 or to a handful of related viruses (e.g., coronaviruses). On the other hand, maybe TLR7 deficiency does disrupt the immune response to a wide variety of viruses, but it took a large-scale viral outbreak for the rare deficiency to be discovered.

The IUIS IEI/PI list is likely to keep growing. Not only will new circumstances highlight PIs that may have gone under the radar, but our increased understanding of PIs is likely to further fragment them into precise, genetically-defined disorders.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.