-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can manage it. Learn about PI diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Research Grant Program

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Getting prior authorization

-

Clinician education

-

Survey research

-

Participating in clinical trials

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Research Grant Program

Bevan McLachlan tracked his son Harry’s health in a spreadsheet after learning the toddler had systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SJIA). He monitored daily fevers, activity levels, and diet.

“Because at that time, we were thinking, if you've got this for life, let's give you the best quality of life possible. And if there's anything that particularly triggers you and gives you a worse day, let's avoid that,” said Bevan, whose family lives in Newcastle, Australia.

Before the diagnosis, Harry had pneumonia in January and never fully recovered his energy. By May, he felt excruciating pain in his ankle, couldn’t walk, suffered ongoing fevers, and was listless. His parents insisted doctors admit him to the hospital after X-rays showed no breaks or sprains in the ankle.

“They did all the tests and said, ‘There's nothing wrong.’ And we just pushed and said, ‘There has to be something wrong,” said his father.

Doctors finally agreed to conduct further evaluations, and after five days, they concluded Harry had SJIA. They prescribed anti-inflammatories and steroids, but the medicine did little to control the fevers. The family worried about macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a full-body inflammation response that sometimes occurs with SIJA and can cause organ damage. Still, the doctors assured them that wasn’t the problem. Meanwhile, Harry grew worse.

“He was really lethargic all the time. He just wasn't himself anymore,” said his mom Rachelle McLachlan. “There were mornings where I would wake up, and if he hadn't come into our room… I was scared to go in his room because I thought that he wasn't going to be alive.”

In June, doctors gave Harry a shot of steroids for his ankle pain, but the fevers raged on. The McLachlans could never have known that a massive infection due to chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) was the root cause of their son’s suffering. But they knew they couldn’t stand by and watch Harry decline. Their next decision—to rush Harry to the hospital—saved his life.

An emergency

When Harry arrived at the hospital in Newcastle, a medical team quickly assessed that he had life-threatening symptoms and stabilized him for transfer to Sydney. Trauma doctors intubated the toddler and treated him with high-dose steroids and antibiotics, and a medicine called methylene blue to help raise his blood pressure. Harry flew in a helicopter to a Sydney hospital equipped with life support machines while his parents made the two-hour drive.

“In my opinion, what the doctors did in Newcastle saved him. The methylene blue, the antibiotics, the steroids to calm the macrophage activation syndrome, all of that early treatment was, basically, what won the battle,” said his dad.

In Sydney, doctors determined that Harry had a multi-organ failure due to MAS and sepsis. Doctors discussed removing his spleen if it didn’t recover and put him on kidney dialysis for a few days. They worried about the function of his lungs and his brain.

By the end of the first week, though, Harry improved, and doctors took him off the intubation and dropped the morphine and medicine needed to get blood to the organs. After 10 days, Harry opened his eyes but didn’t talk.

“It was quite scary. And that's when we thought there could have been brain damage because he woke up and had this vacant kind of look. He was looking at us, but he wasn't smiling. He wouldn't speak. And that was a few days, and we were really nervous,” said his mother.

“Two or three days later, I think we finally got a smile and a giggle, and then eventually he started saying things like, ‘I love you, Mommy.’ And we thought, ‘Oh, he's in there. Thank God.’”

Because of the COVID-19 protocol, only one person at a time could be with Harry in his room. Bevan and Rachelle saw each other briefly when they changed shifts during the three-week hospital stay. They coped with the stress in different ways. Rachelle reached out to family and friends through phone calls, texts, and social media. Bevan journaled.

“Eventually, once we felt comfortable enough, I shared and just asked for prayers on my Instagram page and had a huge amount of support through that, which was really good,” said Rachelle.

Infectious disease doctors ran numerous tests on Harry and found that Burkholderia cepacian (B. cepacian), a bacteria most people can fight off, caused Harry’s infection. B. cepacian results in respiratory illnesses like chest congestion, cough, wheezing, and fever.

“After that finally came through, the infectious diseases team was a bit puzzled at that point because they were trying to work out why this particular bacteria?” said Bevan.

A diagnosis

Harry arrived back at the hospital in Newcastle in the evening, and early the next morning, an immunologist came into his room and said he’d just missed seeing Harry three weeks ago before he was flown to Sydney. He told them he suspected CGD, a disease he’d treated in other patients, and that the treatment, if the family chose, was a bone marrow transplant (BMT).

“What we thought was, ‘My gosh, he survived this crazy thing.’ And at that point, we thought he still had arthritis, and we were thinking, ‘We can't believe he survived. This is amazing. We have our boy.’ We were on a high because he was alive,” said Rachelle.

“And then when we were given this new diagnosis, we're thinking, ‘Oh my God, our journey's not over here. It doesn't stop here. We've now got a bone marrow transplant or a life of infection, managing this immunodeficiency.’”

Bevan expressed his frustration too.

“I was just a little skeptical as well because we've just been through enough doctors and given enough diagnoses. I actually said to him, ‘Look, I appreciate your diagnosis, but at this point in time, I need you to be 100% certain because I'm just not ready to accept this new diagnosis,’” he said.

The immunologist empathized with their concern and told them he’d confirm CGD with a genetic test. Meanwhile, as the McLachlans researched the quality of life with CGD, it became clear that BMT was the best treatment for Harry, despite the risks of side effects from conditioning with chemotherapy and graft versus host disease (GVHD).

After diagnosis confirmation of X-linked CGD in July 2021, the family waited until September 2022 to have Harry undergo the BMT. It gave doctors time to find a donor and allowed Harry to build up his strength. The family grew close to the medical team throughout the experience.

“They said, ‘You’re going to be seeing a lot of us over the next few years, and we're going to become like a family. So, we want you to feel like we are family.’ And they've just definitely become part of the family,” said Bevan. “In fact, we just can’t say enough good things about them.”

Despite being on prophylactic antibiotics and antifungals, Harry developed several health issues, including infections that required hospitalization on and off through January 2022. Bevan recalls one such instance where a doctor (not on his immunology team) tried to tell the family that Harry may have asthma. Instead, after Bevan explained Harry’s diagnosis, a CT scan revealed a granuloma (a mass of cells caused by CGD) growing in his chest. The immunology team addressed it immediately.

“You know, as parents, you're the frontline. You're the advocates. You know him the best,” said Bevan. “You know the doctors have solutions, but only you know his full history. You carry it in your head.”

A treatment

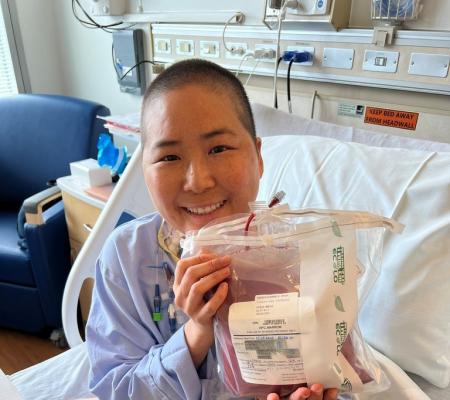

Harry received his BMT on September 28, 2022, with stem cells from an adult donor in Germany who was a perfect tissue match for the then 4-year-old. Except for mild side effects from the conditioning with chemotherapy, Harry “just made it easy for us,” said his parents. Administering the stem cells to Harry took about 30 minutes.

“You stick it up, plug it in, and off you go,” said his dad of the bag of stem cells. “You just watch this magic trickle in.”

Harry stayed in an isolation room at the Sydney hospital for five weeks with either Bevan or Rachelle as they alternated between the hospital and a nearby hotel. A few days before Day 100 of the transplant, an important milestone day in recovery from BMT, doctors cleared him to go home, just in time for Christmas.

Harry, who celebrates his fifth birthday on June 28, continues to improve and has full donor chimerism, which means all of his cells are now healthy donor cells. He plays outside, enjoys building with his toys, and looks forward to starting school in 2024.

“He's quite outgoing, especially with us. He does seem to be a little bit shy when he first meets people, but he's very outgoing and super sweet but cheeky. And he's very sweet with his sister. He's got a big heart,” said his parents.

For those just beginning the CGD journey, the McLachlans said parents should follow their intuition.

“We have now met probably over one hundred medical staff, and every one of them genuinely wants to help you, and make you feel heard. But if it doesn’t feel right, you just have to keep pushing and trust your instinct,” said Bevan and Rachelle.

“It’s like that night that we ended up going to the emergency department. Retrospectively, if we hadn't trusted that instinct, even though we'd been talking and stressing about certain things and being brushed off a little bit, if we hadn't done that, it would have been a very different story than we have now.”

Related resources

Man with X-linked hyper IgM first-ever to receive novel gene therapy

Pharmacist with CVID receives bone marrow transplant

Undiagnosed: Reuben & Sherri Johnson on CGD, chronic illness, and the fight for healthcare

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.